|

12.3 Filtering

Filtering images—i.e., deciding

which ones to post-process and which to skip (or even delete)—is

probably the most time-consuming aspect of digital bird

photography. Because digital cameras allow you to take many more

photos than you would have been likely to take with a film camera, the

tendency among many photographers nowadays (including both amateurs and

pros) is to take far more photos than necessary. The good thing

is that this affords more opportunities to get an exceptional

photo—e.g., a chance capture of the bird very briefly assuming a novel

pose. The bad thing is that you then have to sift through massive

numbers of image files later on, to find the ones worth keeping and/or

publishing. In many cases, that process of sifting through images

can take far more time than it took to actually capture the images out

in the field. In this section we’ll discuss methods for

efficiently filtering large numbers of image files.

The first issue we’ll focus on is learning how to

decide which images to keep and which to discard. This is mainly

a problem for beginners. The key is to be very picky when

choosing which photos to “publish” (i.e., which ones to post on your

web page). A wise man once said: “An amateur photographer is one who

shows all of his photos—even

the not-so-good-ones—to the world. A professional photographer is simply

an amateur who has learned to show the world only the few photos that turned out

exceptionally well.”1

This has some truth to it. If after taking 10,000 bird photos you

were to pick out the best three and show those to a random person, it’s

reasonably likely they would be impressed with those three

photos—especially if they got the impression that you had taken only

three photos in total. The point is that the vast majority of

bird photos that most people take are dull and uninteresting to other

people. By taking enormous numbers of photos and keeping only the

best 1%, you’ll begin to see how a successful photographer can build up

a portfolio of stunningly impressive images. The trap that many

beginners fall into is that they get impatient and want to keep 75% of

their photos. Of course there’s nothing wrong with keeping all of

your photos, but if you plan to share your art with the world, it’s

better to hide the 99% that are run-of-the-mill images and reveal only

the 1% that are remarkable. That’s where filtering comes into

play.

Before you can perform efficient filtering of large

numbers of photos, you need to find a convenient way to quickly view

images. If Adobe Camera Raw (ACR) loads quickly on your computer,

then you can simply use ACR to preview images. On some computers,

however, the time it takes ACR to load your image after you

double-click the filename in the file browser is simply too long.

On some operating systems, the file browser provides its own built-in

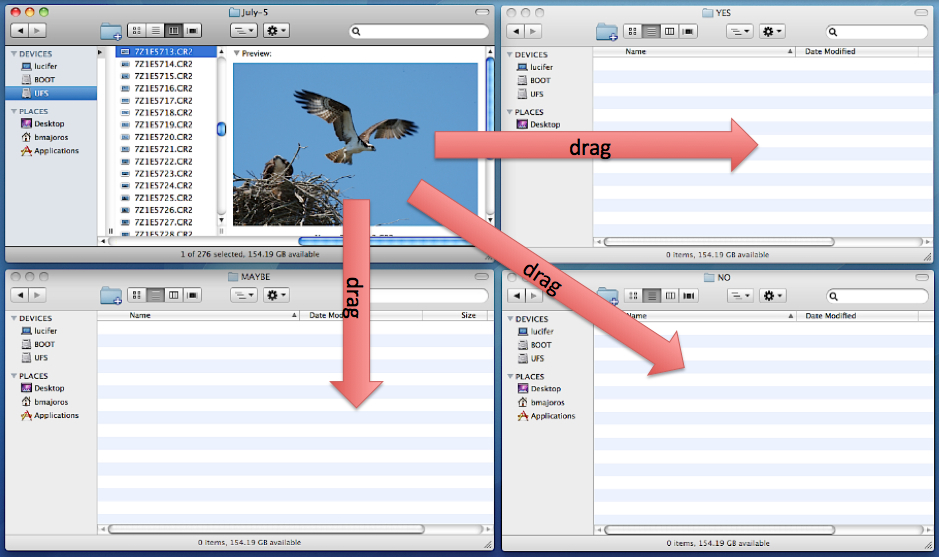

preview functionality. The figure below shows one mode of the Finder utility in Mac OS X version

10.6 (so-called Snow Leopard),

in which previews of multiple files are shown in a 3-D lineup. By

resizing the Finder window you can enlarge the preview thumbnails so as

to provide more detail. In many cases, this preview will be large

enough to allow you to decide very quickly whether a photo is even

worth opening in ACR.

Fig.

12.3.1: Efficient filtering of vast numbers of image files requires some

way to quickly preview each image. The Finder in Max OS X

provides a

quick preview of each image; though the preview is small, it’s enough to

assess overall scene composition and exposure. Images that pass

that test

can then be opened in the Preview utility of OS X for a closer

look. Similar

utilities are available in Microsoft Windows and Linux.

When the tiny

thumbnail isn’t informative enough, you can sometimes get a quick

preview of a file by opening it in some lightweight utility program

rather than opening it in ACR. In Mac OS X you can open image

files (even RAW files, for supported cameras) in the built-in Preview program that comes with Mac

OS X. This program loads quickly, so that on some computers it is

more efficient to open files in Preview first, rather than in

ACR. For those images that look promising in Preview, you can

then close them and re-open them in ACR. The Preview program in

Mac OS X also allows some image manipulation, which is useful inasmuch

as the manipulations that it performs are very fast. Thus, if you

open a photo in Preview and it appears blurry, you can quickly discover

how sharpenable the image is by adjusting the Sharpness slider in Preview.

This technique will give you only a rough indication of the

sharpenability of the photo, but with practice you can develop some

intuition for which photos seem to be sharpenable enough in Preview to

warrant opening them in ACR and proceeding with full

post-processing.

To reiterate, the point of all this is to quickly

identify those images that do not have the potential to become great

images, so that you can quickly discard those files and move on to more

promising ones. It’s all about managing your time and avoiding

wasted effort. As you get practice with large-scale filtering,

you’ll naturally fall into a rhythm that allows you to work most

efficiently on your particular computer system.

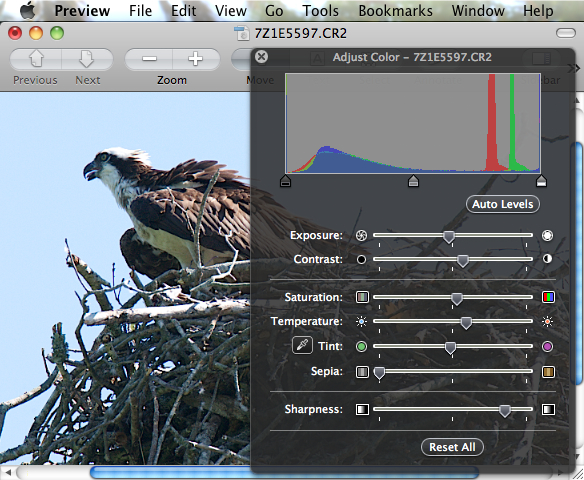

Fig. 12.3.2:

Assessing image sharpenability in the Preview utility of

Mac OS X (similar utilities are available for other operating systems).

This utility can open RAW files very quickly—sometimes more quickly

than Photoshop. If the image looks good in Preview, it’s then

worthwhile

opening it in ACR/Photoshop for full post-processing. Note that

if ACR

opens quickly on your computer, you can skip the Preview step.

Note that when we say that filtering is about discarding images, we don’t

necessarily mean deleting

those images. For images that are clearly of no use

whatsoever—e.g., that are totally blurred, or massively underexposed or

overexposed—you may indeed want to simply delete them during

filtering. On Mac OS X systems, deleting a file in the Finder can

be done instantaneously by pressing the key combination Cmd-delete, so deleting files

needn’t take any more time than simply skipping them. For images

that aren’t defective per se, but appear rather unexciting, you may

instead want to skip them rather than actually deleting them from your

hard drive, in case you later find a use for them. I rarely

delete files anymore, since the rate at which hard drives have gotten

larger over the years has kept pace with my rate of taking photos (and

the rate at which the file sizes have increased, due to the megapixel

race). However, the good thing about deleting files that are

clearly useless is that later searches through your archive can proceed

more quickly, since there will be fewer files to examine. Note

that most operating systems nowadays have a trash can mechanism, so that after

deleting a bunch of images you can go back and make sure you really

wanted to delete them before emptying the trash can (which permanently

deletes the files).

The way I like to filter a directory of images is to

create three subdirectories, called YES, MAYBE, and NO. As I

preview the images, I note which ones I definitely want to publish, and

I drag those into the YES folder (see the figure below). For

those that are clearly of no use to me, I drag them into the NO

folder. All others I drag into the MAYBE folder.

Fig. 12.3.3:

Filtering images via drag-and-drop. I classify my images

into quality categories (best to worst) and drag them from the main

directory to an appropriate subdirectory. When all images have

been dragged to a subdirectory, I then review the highest quality

category and possibly subdivide those as well. The goal is to pull

out the “best of the best” and publish

only those.

When deciding

which files to drag into the YES versus MAYBE or NO folders, I apply

what I call the BBLP rule,

where BBLP stands for Beautiful

Bird, Lousy Photo. Whenever I see an image of mine that

depicts a bird that is clearly a beautiful specimen, but that has been

poorly captured in the image, I say that it is a beautiful bird, but a

lousy photo. Many beginners have difficulty skipping over photos

that depict what they know are beautiful birds, but that have been

captured by a truly horrendous photo (whether due to blurring, poor

exposure, or any other technical or aesthetic shortcoming). For

some people this can be a severe mental block, because they fail to

acknowledge that a photo can be lousy even if the bird that was

photographed is a truly beautiful specimen. They may even feel

that by deleting the photo they’re somehow offending the bird.

This is where the mantra of BBLP comes into play. Telling

yourself that the bird is beautiful but the photo is lousy may allow

you to more easily detach yourself emotionally from some of your more

mediocre images, so that you can focus more fully on the more promising

images in your collection.

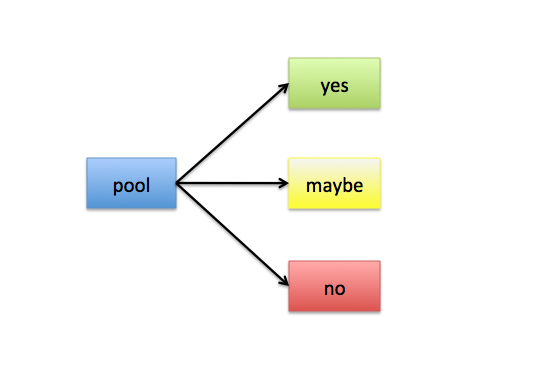

Fig. 12.3.4: My

classification schema for image filtering.

I quickly classify each image into the YES, MAYBE, or NO

categories. The YES photos will get uploaded to my web site;

all the others will remain unused.

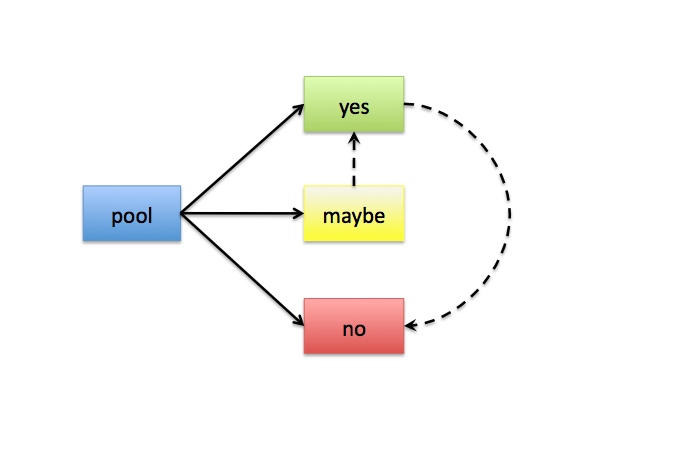

After performing an initial pass to classify all

files as YES, MAYBE, or NO, the main directory will then be devoid of

image files. At this point I then look to see how many files are

in the YES subdirectory, and ask myself whether I’ve got too many or

too few YESes. If I think there are too many YES files, I’ll then

re-examine each and every file in the YES subdirectory and

painstakingly find the least promising among them, which I then drag

from the YES subdirectory into the NO subdirectory (or perhaps into

MAYBE instead). Conversely, if I realize that the YES

subdirectory contains fewer images than I’d like, I may decide to

re-analyze the files in the MAYBE subdirectory and drag the very best

of those into the YES subdirectory. I’m also careful to make sure

that no two images in my YES bin look too similar to each other; if

I’ve got many excellent images of a bird in the same pose or very

similar poses on the same perch, I’ll force myself to pick only one.

Fig. 12.3.5:

After the initial filtering step, you can then revisit some

of the decisions you’ve made by dragging some of the best MAYBE

photos into YES, and/or dragging some of the more questionable

YES photos into MAYBE. These decisions are often very difficult

to make, so it’s good to make a second pass through the entire set,

preferably after resting your eyes for several hours, to see if you’ve

changed your mind about any of the images.

Once I’m satisfied that the images in the YES subdirectory

are indeed those that I want to publish from this set, I move the

entire contents of the YES subdirectory back up to the parent

directory, and then consolidate the MAYBE and NO sets into a single

subdirectory called UNUSED. In this way, I still have access to

the unused images from each set, in case they prove useful at a later

date (such as for documentation purposes). The YES photos I’ll

typically upload to a single photo album or blog on my web site.

Note that filtering can be applied either to your

RAW archive or to your collection of post-processed JPG images.

Indeed, there is good reason to apply filtering to both. During

post-processing, I generally perform a simpler form of filtering on the

RAW images: I simply skip through the files in each each directory

until I find one that piques my interest. I then post-process

that image into a JPG file, which goes into my (separate) JPG

archive. Once I’ve gone through all the RAW files in a given

directory, I then perform a separate pass of filtering on the

post-processed JPG files, using the YES/MAYBE/NO protocol described

above. The YES images then get uploaded to a single page on my

web site. If a client then finds an image on my web site that she

or he wants to re-publish in another medium, s/he can simply send me

the URL (internet address) of that photo from my web site. I then

track that JPG back to its RAW file and then re-process the image to a

higher-resolution JPG or TIFF which I can then deliver to my client.

Filtering mountains of image data is a tiring

process. Keep in mind that many of the post-processing decisions

you make (including your filtering decisions) can change as your eyes

get tired, your attention span shortens, or the lighting in your work

space changes. During subsequent post-processing sessions I often

double-check images that I’ve already post-processed, and often I’ll

find that I feel differently today about an image that I post-processed

(or filtered) yesterday. This is a natural part of the artistic

process. Just remember that post-processing images can be at

least as difficult as capturing them in the field, and deserves at

least as much effort and attention if you want to achieve your full

potential as a digital artist.

1 Liberally adapted from a quote by Ryszard

Sytnik.

|

|

|