|

13.5 Merging

Poses

The nice thing about digital

photography is that with a copious stash of memory cards you can take

far more photos in the field that you’d be likely to do if you were

shooting film. This allows you to be pickier when choosing which

of your images to share with the world. If you’re a real

perfectionist, however, you may find that for a particular subject you

simply have no photos that satisfy all of your aesthetic

preferences. Sometimes, however, you’ll notice that one of your

images satisfies some of your requirements, while other photos of the

same bird satisfy other requirements. In these cases you might

consider merging these images, keeping the best parts of each image for

inclusion in the final, composite image. We’ve already been doing

this in the preceding chapters: first as we merged the background of

one image with the foreground of another image, and then as we merged

portions of differently exposed photos in the case of HDR. In

this section we’ll consider yet another application: merging different

poses of a bird into a single, “frankenstein” creature.

Fig. 13.5.1: Two images of the same bird in different poses.

The left image features some nice wing action, but the angle

of the head isn’t ideal. The right image features a better profile

of the head, but lacks any wing action. These photos can be

merged to combine the better aspects of the two poses.

The figure above shows two photos

of the same bird. The left photo features some nice wing action,

though angle of the head isn’t ideal—if it was turned a tiny bit to the

right, a better profile would be presented. The photo on the

right

features the same bird presenting a slightly better profile, though

unfortunately it’s facing left instead of right, and it’s slightly

larger in frame. We’ll show how to very easily overcome both of

these issues, resulting in an image that can be merged into the first,

thereby combining elements from both poses.

The first thing to do is to mirror the second image

(the right image in the figure above) so that the bird is facing to the

right. This is as simple as invoking Image > Rotate Canvas > Flip Canvas

Horizontal. Once this is done, we can begin thinking about

how to

resize the image so that the bird’s proportions match those in the left

photo. The first thing to do is to ensure that both images are

being viewed at the same zoom level. The two photos can then be

positioned side-by-side on the screen, with the scroll bars adjusted so

that the bird’s head is clearly visible within the window

frame. Now we can invoke the Image > Canvas Size tool and try

different sizing proportions (see section 12.7)

until we find one that

equalizes the sizes of the two birds. If you wish to be

more exacting, you can use the Ruler

tool to measure various dimensions

of the bird (e.g., its beak length) in the two images. Just keep

in

mind that some measurements can be deceptive, due to different angles

(e.g., foreshortening of features due to camera perspective).

The next step is to select a portion of one image to

be merged into the other image. For this example we’ve selected

the bird’s head from the rightmost image in the above figure, and

copied it via Cmd-C / Ctrl-C.

We then pasted this selection as a

new layer in the other image (the leftmost photo in the above

figure). The figure below shows the Layers panel resulting from

this operation. The top layer contains only the bird’s head from

the other photo.

Fig. 13.5.2:

The Layers panel after copying

the bird’s head from one photo into another.

Though not shown here, a layer mask can

be used to trim the new head and aid in

blending it with the lower layer.

What remains

now is to adjust the new layer so that it blends in seamlessly with the

lower layer. First we’ll need to invoke the Move tool (press V)

and use the mouse cursor to drag the new head into place in front of

the

old head in the lower layer. In this case, some parts of the old

head

ended up still being visible behind the new head (not shown

here). There are several techniques that could be used to rectify

this, including the use of the Clone

tool and/or the use of layer

masks. We opted to use the Clone

tool, since it’s generally very

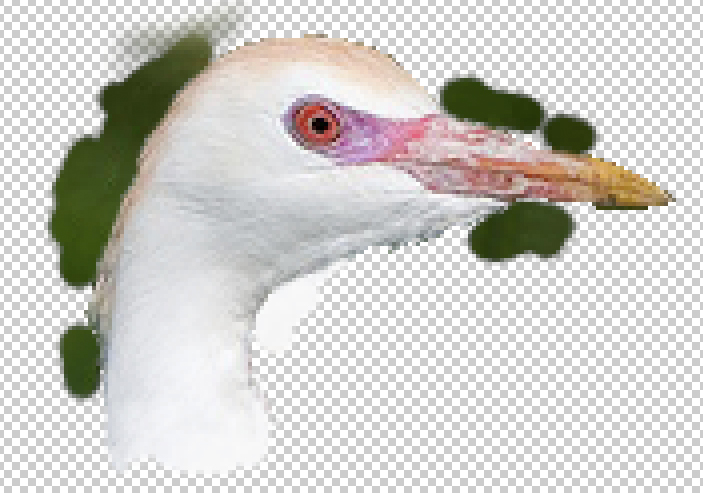

fast and convenient. The figure below shows just the top layer

after the Clone tool was

applied to cover up parts of the old head

showing through. The source for the Clone tool was taken to be a

region of the background layer close to the drawing (target)

location.

Fig. 13.5.3:

The new layer after some touch-up with the Clone tool.

Pixels from nearby areas of the lower layer were cloned into this

layer to cover up parts of the old head that were showing through.

The Eraser tool was also used to trim away some of the darker

background pixels from around the new head.

In addition to

the Clone tool, the Eraser tool was

used to trim away some unwanted pixels from the new

head. Recall from previous sections in this chapter that it’s

sometimes useful to enlarge a selection before copying pixels, to

ensure that nothing is inadvertently omitted. In this case, some

of the pixels around the new head were slightly too dark, and needed to

be trimmed away using the Eraser tool;

a layer mask could equally well

have served this purpose.

The figure below shows the result. The top

image is the original; the bottom is the composite image featuring the

better head profile.

Fig. 13.5.4:

The result of merging the poses. Top: one of the two original

images. Bottom: the final “frankenstein” image, after

grafting the head from

another image onto this body. Merging poses takes time and

effort, and is

perhaps best left for the birds that are most special to you, or most

rarely seen.

Like replacing the background of

an image, merging different poses of a bird can be time-consuming; I

rarely ever do it, because of the time and effort involved. These

types of highly manipulative techniques are perhaps best left for those

rare cases where you’ve got a photo of a very special bird (e.g., a

species rarely seen in your area), but the photo isn’t ideal and you

don’t have the option of simply taking more photos of the bird in hopes

of getting the ideal image.

A related application is that of adding canvas when part of the bird

(typically the wingtips) have been clipped. Personally, I think

some photographers put too much emphasis on the issue of clipped

wingtips; when proportions are fixed by publication constraints, the

logical (if not artistic) desire to retain all extremities often needs

to take a back seat to the more important consideration of subject size

and position in the frame, and it’s doubtful in many cases that general

viewers would find the clipping of a bit of wingtip to be that terribly

offensive, given current trends in artistic photography.

Nevertheless, it’s sometimes the case that you’ll wish you had captured

more of the scene around the periphery of the photo. The same

technique described above can be used to clone in extremities such as

clipped wings or feet from other photos of the same subject.

You’d first have to expand the image via Image > Canvas Size, to make

room for the addition of grafted elements. Once this is done, you

can copy a selection from a second image and past it into the

(enlarged) first image, or use the Clone

tool with the cloning source set to the other image. When

choosing a new canvas size, it’s usually best to over-estimate how much

additional “canvas” you’ll need, since you can always

crop the image later using the Crop

tool.

Note that if you’re desperate to re-create a clipped

wingtip or other extremity but don’t have any other photos of the same

bird that you can use, you can sometimes get away with mirroring the

symmetric feature from, e.g., the bird’s other wing or other

foot. This needn’t be as difficult as it may seem. Though

the source for the clone operation will likely be at the wrong angle

and orientation, the rotation and mirroring tools available under Edit > Transform will often

prove sufficient to achieve the desired effect.

Another possible use of this technique is when

you’re shooting with an extremely shallow depth-of-field (DOF), so that

only part of the bird can be in-focus in any one image. You might

conceivably want to try merging the different in-focus regions from

different shots, to produce a composite image having all or most of the

bird in focus. There are surely other applications that one can

think of. The wonderful thing about digital processing

technologies is the great flexibility that they afford the creative

mind. And creativity is a good thing.

|

|

|