|

11.3 Correcting

Exposure

Whereas the previous section

addressed the specific issue of blown highlights—i.e., bright regions

of an image that have been overexposed to the point that details are

lost—in this section we deal with the more general issue of adjusting

exposure for the entire image. This includes images that are both

over-exposed (too bright) and under-exposed (too dark). We’ll

also consider how to manipulate the lighting patterns in the scene so

as to achieve more even lighting, as well as exposing the bird

differently from the background.

11.3.1

Fixing

Underexposure

Underexposure is one of the most difficult problems to correct in

postprocess. If you follow the ETTR/BETTR protocol (section 6.2),

you’re much more likely to overexpose than underexpose, and in

general, that’s a good thing, because as long as you don’t clip the

highlights, your overexposed images can generally be corrected without

loss of information. Underexposure can, however, occur, even for

photographers adhering to the ETTR principle. One common example

is when you’ve been shooting a pure white bird in bright sunlight in

manual exposure mode

and you suddenly encounter a non-white bird in the shade nearby.

Unless you remember to readjust your exposure settings, this new bird

is likely to be massively underexposed. The figure below shows an

example of an extremely underexposed image.

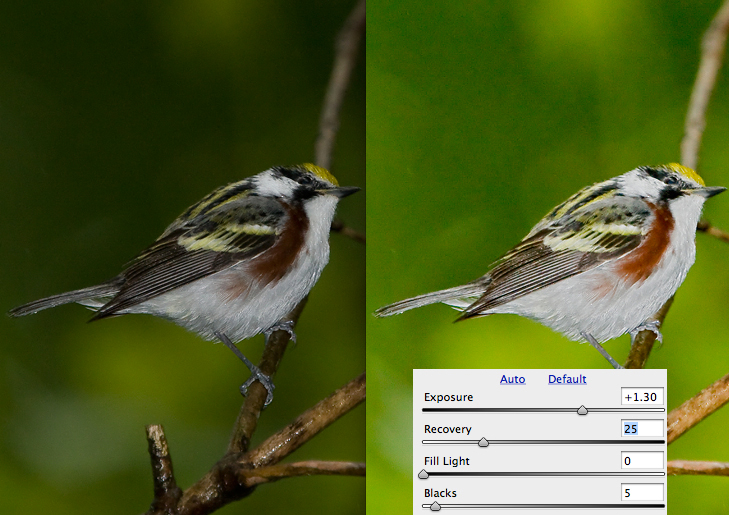

Fig. 11.3.1: An

extremely underexposed image, and attempts to correct it.

Left: the original image. Center: after increasing exposure

digitally in ACR.

Notice the background noise and the overall poor image quality.

Right:

after reducing noise and increasing sharpness in Photoshop.

Notice that

the colors are quite poor. There’s a limit to what you can do

with images

this massively underexposed; shooting in RAW definitely helps.

In the leftmost pane of the above figure is

the original RAW image. The middle pane shows the image in Adobe Camera Raw (ACR) after

increasing the Exposure

slider in ACR to its highest setting. Notice the enormous amount

of noise in the background. The rightmost pane shows the final

image in Photoshop proper, after sharpening and noise reduction.

Though it’s impressive that so much information was able to be pulled

out of such a massively underexposed photo, the resulting image doesn’t

look great. The overall color has suffered from the underexposure

and the measures that were taken to correct the exposure.

Nevertheless, this example does illustrate the advantage of shooting in

RAW: if the original image had instead been a JPG, the degree of

information recovery illustrated here would have been utterly

impossible.

The example below shows a more tractible case, in

which the image is only slightly underexposed. In this case we’ve

again increased the brightness of the image via the Exposure slider in

ACR (note that the Fill Light

slider is often useful for this purpose as well, though we didn’t use

it here). Doing so created some blown highlight regions, so we’ve

also adjusted the Recovery slider to protect those areas. The Brightness slider (not shown here)

can often be just as useful as the Exposure

slider, and sometimes even more so. The exposure shown here is

far from perfect, but is at least brighter than before, and can now be

fine-tuned in Photoshop proper.

Fig. 11.3.2:

Increasing brightness via the Exposure slider in ACR. Be careful

to check how the defaults are set for the other sliders, since this can

work against

you if you don’t change them.

Correcting exposure in ACR is typically the most effective option,

since it’s the option that has the most information available to

it. Once the photo case been converted from RAW to the internal

representation used by Photoshop proper, certain information will have

been discarded and can’t be reclaimed without going back to the

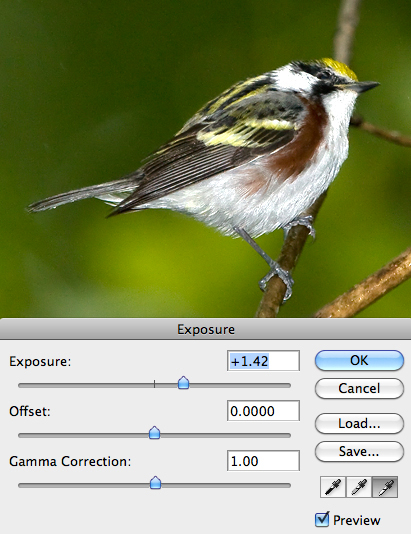

original RAW file. The next example (below) shows the effect of

adjusting exposure via the Exposure tool in Photoshop proper. As

you can see, in order to achieve an overall brightness level similar to

that for the previous example we’ve had to blow the highlights in the

bird’s cheek and throat. Whereas in ACR we could guard against

this by adjusting the Recovery

slider at the same time, once the image is in Photoshop proper (i.e.,

after it’s been converted from RAW), that’s not possible. By and

large, highlights that you’ve blown via adjustments made in Photoshop

proper aren’t directly recoverable.

Fig. 11.3.3:

Increasing brightness via the Exposure slider in

Photoshop proper (rather than ACR). This method often results

in blown highlights, so I don’t recommend it.

Note that in the Exposure tool there is a slider called Gamma Correction. While the Exposure slider in Photoshop proper

tends to be unwieldy for images having bright white regions, the Gamma Correction slider can be very

useful, both for increasing brightness and for decreasing it. In

the example below we’ve gone back to the original image and increased

brightness by adjusting the Gamma slider in the Exposure tool.

Increasing brightness this way often results in a decrease in the

overall contrast of the image, but this can be corrected subsequently

via the Brightness/Contrast

tool or the Levels tool (we’ll get to those tools in just a minute).

Fig. 11.3.4:

Increasing brightness via the Gamma slider in

the Exposure tool. Reducing gamma increases brightness,

but it can also reduce contrast; you can compensate by

increasing contrast later via the Brightness/Contrast tool

or the Levels or Curves tools.

Note that in all of these examples we’ve made sure that the Preview button is checked.

This allows you to see the effect of your changes immediately. To

compare the new settings to the original image, you can simply toggle

the Preview button on and off

repeatedly. This is an extremely useful feature, because it

provides context and allows you to judge the effect of a tool relative

to the unmodified image.

In the next example we again return to the original

image and correct the exposure using the Brightness / Contrast tool.

Here we’ve increased the Brightness

slider substantially, and you can see that it has increased the overall

image brightness without blowing the highlights. We’ll see in the

next section that the Contrast

slider can be useful for restoring contrast in overexposed images,

though there are more flexible ways to adjust contrast, as we’ll see.

Fig. 11.3.5:

Increasing brightness via the Brightness/

Contrast tool.

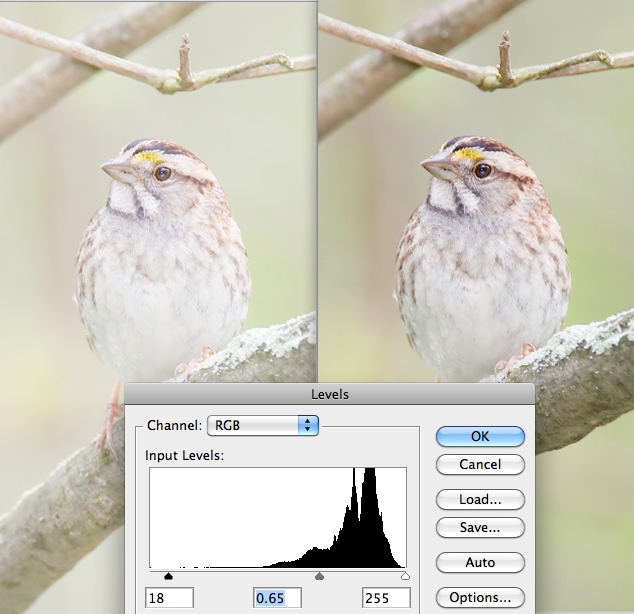

The next tool is one of the most

useful tools in Photoshop for adjusting brightness and contrast.

It can also be used as an alternative to the Highlights tool to recover

blown highlights. This is the Levels

tool (see below), which shows you the image’s current histogram and

allows you to set sliders that reshape that histogram. The

sliders in this case are the small triangles (actually pentagons) below

the histogram and below the Output

Levels track. In the current example, we’ve moved the

leftmost (black) and middle (gray) sliders below the histogram.

Fig. 11.3.6:

Simultaneously increasing brightness and contrast

via the Levels tool. The triangles/hexagons under the histogram

are the sliders. The black slider increases blacks, the white

slider

increases whites, and the gray slider can increase or decrease

overall brightness, depending on which way you slide it.

The middle (gray) slider adjusts

the overall brightness; in the example above we’ve moved it toward the

left, which increases brightness. In order to restore some

contrast, we’ve moved the leftmost (black) slider a bit to the right,

which darkens darker colors toward black. Another way to increase

brightness is to move the rightmost (white) slider for the histogram to

the left; this increases lighter hues toward pure white. If you

slide that white slider too far left (i.e., into the region of the

histogram having nonzero height), you’ll induce clipping of highlights,

so be careful. This slider is mainly useful for making sure that

the brightest point in the image is true white (rather than gray),

which helps to foster the impression of high dynamic range. The

sliders beneath the Output Levels

track are less often useful, because they have a fairly drastic effect

on the image. We’ll see later that sliding the white slider all

the way to the left is useful for fixing eye-shine, by making the

selected region (the eyes) pure black. We’ll see that there are

many uses for the Levels tool; this tool is very simple to use, fast,

and often highly effective for adjusting brightness or contrast either

in the entire image or in selected regions (as per the D-PIE technique: Differential Processing of Image Elements).

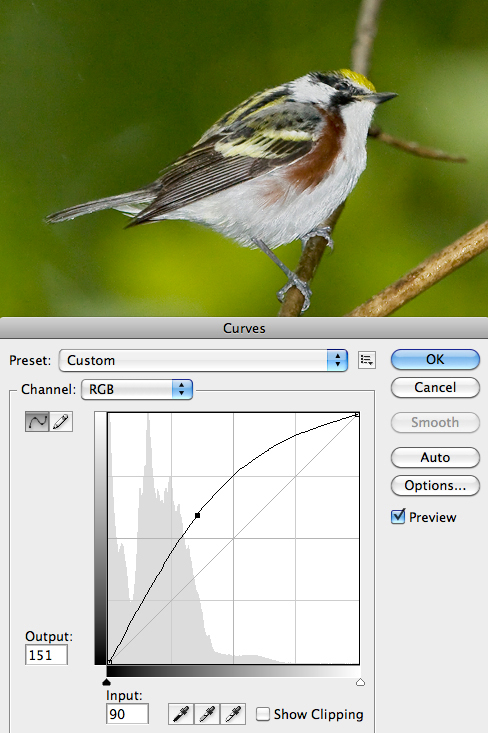

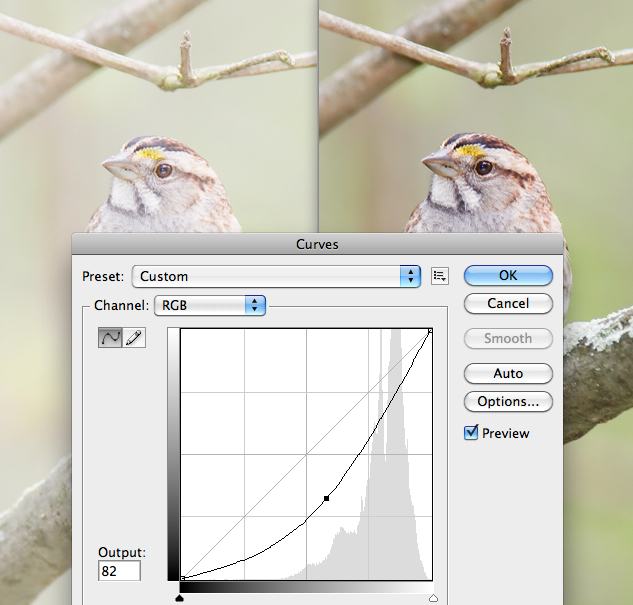

The next tool is one that I find to be too unweildy

for most tasks, though it is a popular tool among avid

Photoshoppers. This is the Curves

tool, which allows you to superimpose a curve onto the histogram to

indicate how you’d like to transform the brightness profile of the

image. In the example below, we’ve increased the overall

brightness of the image by applying a convex curve that concentrates

the increase in the middle tones, with progressively less change toward

the extremes. This type of nonlinear transformation is useful for

increasing overall brightness without blowing the highlights or

softening the blacks.

Fig. 11.3.7:

Increasing brightness via the Curves tool. I find this

tool very unwieldy, and rarely use it, but others swear by it.

In this particular case the Curves tool has done a very decent

job of improving this image, and it took only two seconds to

accomplish. Notice the tiny black square on the curve. The

way we drew this curve was by clicking the mouse on the diagonal line

(the one that runs from the lower left corner to the upper right

corner) and dragging this point upward until the curve assumed the

shape you see above. Because the Preview box is checked, we were

able to see the effect of this transformation on the image in

real-time. Simple adjustments like this can be performed in no

time flat using the Curves

tool. Note that you can now refine this curve by clicking

anywhere on the curve and dragging that point up or down. By

repeating this process you can create a whole set of anchor points that

define an arbitrarily complex curve. In theory, this is an

extremely flexible means of adjusting an image’s histogram. In

practice, it becomes very tedious and frustrating, because the effect

of moving each point is tempered by the positions of all the other

points you’ve already set. Also, the working space in the Curves window is limited and it’s

hard to make tiny changes at the finest levels. As a result, the

transformation tends to be very sensitive to small mouse movements,

making it difficult to achieve subtle changes. For that reason, I

personally tend to use the other tools much more often, particularly

Levels, Shadows/Highlights,

and the Gamma slider in the Exposure tool.

11.3.2

Fixing Overexposure

For photographers committed to the ETTR technique (Exposing To The Right—section 6.2),

it’s much more common to have overexposed than underexposed

images. While the highlight alerts on your camera’s LCD can help

you to avoid blowing the highlights, for some photos you’ll find that

the resulting image appears too bright, or “washed out”. This can be corrected

using any of the tools mentioned in the previous section (as we’ll

illustrate shortly). The advantage of reducing brightness for

overexposed (but non-clipped) images over increasing brightness for

underexposed images it that the brighter images use larger numbers of

bits to encode their pixels, so no information has been lost, unlike

the case with underexposure, in which fewer bits are used and numerical

precision often suffers as a result. Also, brighter images tend

to be less noisy (as long as they were produced via large apertures or

slow shutter speeds, rather than high ISO settings) than underexposed

images.

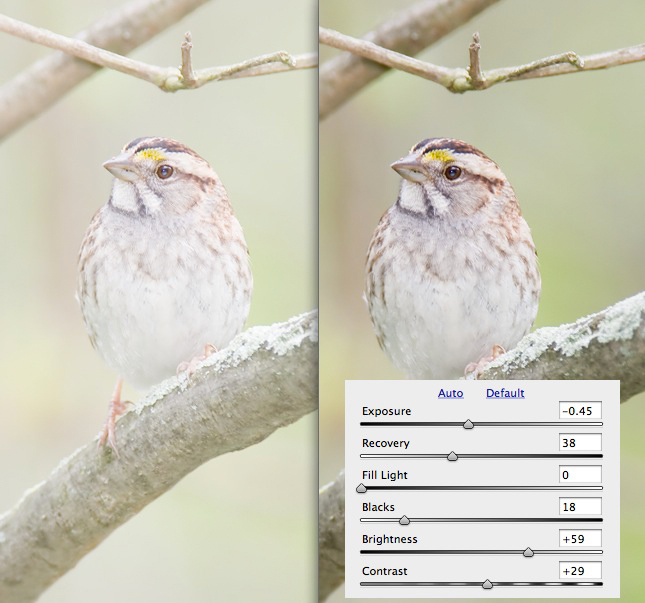

Reducing brightness in Adobe Camera Raw can be

accomplished via the Exposure

slider. In the example below, we’ve decreased the Exposure by

-0.45, while also using the Recovery

slider to reclaim highlights. We’ve also increased the Blacks

setting and then increased the Brightness to improve contrast; the Contrast slider was also adjusted a

bit. Although the resulting image is far from perfect, these

adjustments are appropriately conservative for the RAW conversion

phase, which applies to the full resolution image. Finer

adjustments to the exposure can be performed when the image has been

reduced to its target resolution prior to distribution (i.e., posting

on a web page or printing to photographic paper). Ideal

brightness and contrast, like sharpness and saturation, are very

medium-dependent.

Fig. 11.3.8:

Fixing overexposure in ACR can be done by decreasing the

Exposure setting. Though this will certainly reduce overall

brightness,

you may still need to increase the contrast of the image, since many

overexposed photos appear washed out. Here we’ve increased

contrast

both via the Contrast slider and also by increasing the Blacks and then

compensating by increasing the Brightness.

In the example below we’ve returned to the original RAW image and

adjusted the brightness in Photoshop proper using the Gamma slider in the Exposure tool. Increasing

gamma generally increases contrast and saturation while decreasing

brightness. Like the Curves

tool in its most basic use (see below), Gamma Correction applies a

nonlinear function that leaves pure white and pure black values

unmodified while adjusting mid-tone values (the gamma function is described in more

detail in section 16.2).

Fig. 11.3.9:

Overexposure can also be adjusted in Photoshop proper,

via the Exposure tool. Here, we’ve ignored the Exposure slider and

instead increased the Gamma, which simultaneously decreases

brightness while increasing contrast.

In the next example we instead use

the Levels tool to decrease brightness and increase contrast. By

moving the gray slider to the right, we’ve deformed the histogram so as

to darken the mid-tones, while moving the black slider to the right has

increased the dark presence and enhanced the overall contrast.

Note that we have, in effect, adjusted the three sliders so that the

black slider is close to the leftmost end of the nonempty part of the

histogram, the white slider is close to the rightmost end of the

nonempty part of the histogram, and the gray slider is closer to the

main mass of the histogram. Though not infallible, this procedure

provides a very general set of guidelines for using the Levels tool. Just keep in

mind that moving the black and white sliders into the interior of the

histogram mass will cause clipping of blacks and whites, respectively,

in the image. This is why it’s preferable to keep them at or near

the ends of the visible histogram mass.

Fig. 11.3.10:

The Levels tool is another favorite method for fixing

overexposure. Here we’ve moved the midtone slider (gray triangle

below the histogram) to the right, to decrease overall brightness,

and then moved the black slider to the right a bit to beef up the

blacks in the image.

For the next example we’ve

achieved roughly the same effect using the Brightness / Contrast tool instead

of Levels. In this case

we’ve descreased the brightness and increased the contrast directly via

their respective sliders. Though this appears to be a simpler and

more direct means of adjusting these image qualities, the Levels tool with its visual

representation of the histogram provides more information to guide you

when setting the sliders.

Fig.

11.3.11: The Brightness / Contrast tool can also be

useful for decreasing brightness while also adjusting

contrast, which is commonly required for overexposed

photos.

In the next example we apply the Curves tool. Whereas in the

previous section we dragged the curve above the diagonal to increase

brightness, for this overexposed image we instead drag the curve

downward so as to decrease brightness. Though we’ve again used

only a single point, we could have introduced any number of points to

arbitrarily shape the curve to our liking. Note that a silhouette

of the image’s histogram is faintly depicted in the background of the

curve pane, providing some guidance as to which parts of the brightness

spectrum need attention. The black and white triangles below the

curve act as sliders just as in the Levels

tool, allowing you to set the white/black points and possibly to clip

the histogram at either end. Thus, the curves tool provides all

the information present in the Levels

tool, with the added capability to deform the histogram (via the curve)

in any arbitrary way.

Fig. 11.3.12:

The Curves tool is arguably the most flexible tool

in Photoshop for fixing exposure problems, though I rarely use

it, because I find it unweildy. In this simple example, we’ve

adjusted

the exposure by dragging a point on the diagonal downward, creating

a curve. Overexposure has been substantially reduced, though the

image now exhibits saturation problems.

Finally, we consider the use of

the Shadows / Highlights tool

for decreasing brightness. By increasing the Highlights slider we’ve decreased

the overall brightness of the image.

Fig. 11.3.13:

The Shadows / Highlights tool is typically not the

best one for fixing overexposure, but in some cases it works. It

is, however, extremely useful for fixing the blown highlights (not

shown here) that often accompany overexposure.

It should be clear by now that

Photoshop (and Adobe Camera Raw)

provide numerous, redundant methods for correcting overexposure and

underexposure. Though some methods are more flexible than others,

additional flexibility (via more parameters to be adjusted) is

sometimes more of a hindrance than a help. A good strategy, when

deciding which tool to use for a given image, is to try the simpler

tools first; because of their simpler interface, it should become

quickly apparent whether the simpler tools are sufficient to achieve

the desired effect. However, in order to gain familiarity and

proficience with all the tools, it’s a good idea to vary your routine

and do some exploration before adopting a single favorite tool.

Remember that when all you have is a hammer, everything starts to look

like a nail.

11.3.3

Fixing Uneven

Lighting

When shooting on sunny days, the patterns of sun and shade can work for

you or against you. Unless the sun is directly behind you, a bird

in direct sunlight will generally have at least some part of its body

shaded, and this may or may not look good. As we described in

section 7.6, the use of flash to fill in the

shadows is a powerful

field technique that, unfortunately, is not always as effective as you

may like (due, for example, to distance or exposure constraints).

Fortunately, for many images you can fill in the shadows digitally in

Photoshop, using the Shadows /

Highlights tool introduced earlier. In the example below,

we’ve used the Shadows sliders to lighten the shadows of both the bird

and its environment. Notice how the deep shadows under the bird’s

tail and wings have been lightened to reveal significant detail that

was previously hidden. The shadow on the bird’s face has also

been lightened, and much of the bird’s underside is now lit up as if

fill flash had been used to light the bird from the front.

Fig. 11.3.14:

The Shadows / Highlights tool in Photoshop can be used to re-shape

the lighting patterns in the scene. The top image conveys the

impression of a strong

light coming from above. The bottom image, after strong

manipulation of shadows,

lessens the effect by creating the impression that light is also

shining onto the

bird from other angles as well. Notice the effect on the mood of

the image.

Obviously, the use of fill flash

and digital lightening via the Shadows

tool aren’t mutually exclusive; indeed, the Shadows tool can be highly

effective at enhancing the effect of fill flash in situations where

your flash unit isn’t powerful enough to provide enough fill at the

given distance. The use of the Highlights

tool can also help to reduce the harsh effect of direct sunlight by

mitigating the difference between the sunlit and shadowed regions of an

image. Simultaneously dampening the highlights and lightening the

shadows can make an overly-contrasty image appear more uniform, though

if taken to the extreme it can result in images that appear flat and

dull. Finding the right balance is a matter of intuition,

experience, patience, and luck.

As

with all methods that increase brightness in underexposed regions, the

ability to pull out detail is typically vastly improved by shooting in

RAW and processing your images in 16-bit mode in Photoshop.

11.3.4

Differential

Exposure of Bird and Background

All of the methods described in the preceding two sections can be taken

one step further by applying them differently to different parts of the

image. That is, rather than applying any of the foregoing tools

to the entire image, you can use your favorite selection tool to select

one region of the image (such as just the bird, or just the bird’s

wing, or just its head, etc.) and then apply an appropriate exposure

tool to just that region. You can then repeat this for all the

different parts of the image. This obviously takes more effort,

but potentially offers greater gain, since you can fine-tune the

exposure parameters for each part of the image. Such fine-tuning,

if done well, can in some cases result in images appearing to have

higher dynamic range than

would normally be possible with today’s DLSR’s, because you can pull

the maximal amount of detail out of all parts of the image—including

both the shadows and the highlights. Normally, with today’s

DSLR’s you have to choose between maximizing detail in the bright

regions of the scene (by exposing darker) or maximizing detail in the

dark regions of the scene (by exposing brighter). We’ll see in

Chapter 13 that via the merging of multiple photos having different

exposure settings we can achieve a High

Dynamic Range (HDR) image having more striking color and tonal

ranges and more details in extreme areas of the histogram. When

working with only a single photo, the HDR technique is inapplicable,

but by applying different exposure adjustments to different parts of

the image, you can sometimes achieve an effect similar to HDR.

This is what I call the D-PIE

technique, or Differential

Processing of Image Elements.

The figure below serves as a very rudimentary

example. The top pane shows the original image and the bottom

shows the image after the bird had been separated from the background

(via separate layers) and the twain processed separately using the

Shadows / Highlights tool. As you can see, the background has

been slightly darkened while the bird has been significantly brightened.

Fig. 11.3.15:

By first selecting the bird and moving it to a separate layer,

you’re then free to manipulate the foreground and background separately.

In this case we’ve lightened the bird while darkening the background, to

make the bird stand out more. In this particular case it’s

probably been

a bit over-done. Try to be more subtle when you apply this

technique.

In this case the effect is a bit

exaggerated for the sake of illustration, but it should suffice to

demonstrate the potential of this technique to drastically alter the

relative appearance of the bird versus its background. The

background was slightly darkened by dampening the highlights via the Highlights tool—a subtle technique

I often use to make the background slightly less distracting. For

the bird, the shadows were lifted via the Shadows tool, while the highlights

were very slightly supressed using the Highlights sliders.

There are several things to note about the above

image. First, the effect achieved here is again very similar to

what could be achieved in the field using stronger flash: recall that

flash falls off rapidly with distance, so often the bird is

substantially more affected by the flash than the background. In

the case of true flash, the effect is sometimes too strong, and can be

moderated by applying the above transformation in reverse (slightly

darkening the bird and lightening the background). Second, note

that the changes to the exposure have affected the colors of the

bird. You’ll often find that after modifying the exposure of an

image you’ll want to use the Saturation tool to slightly de-saturate

the subject; this is especially true when you’ve used any of the

exposure tools to darken the bird. Third, keep in mind that all

of the techniques described here have the potential to make the image

appear artificial. Because changes to exposure in postprocess can

alter the perception of the lighting patterns in the image, they can

confuse the viewer by implying lighting patterns that differ between

foreground and background. For example, if you modify the subject

so as to appear to be lit from below, while the rest of the scene is

clearly lit from above, you run the risk of making the image appear

artificial, as if the bird had been pasted into the scene from a

different photo. This might be the effect you want—or it might

not.

Another example of the above technique is shown

below. In this case, the background was brightened using the

Levels tool, to create the perception of a bright sunrise behind the

bird. The bird was processed separately from the background, and

indeed individual parts of the bird were processed separately from each

other to create the impression of greater dynamic range. Some of

the whites were exaggerated to make the bird seem to glow. The

red pupil was desaturated and the yellow iris was brightened to make

the eye look more alive. The bird was also sharpened using the Unsharp Mask (section 11.4).

All of the exposure changes in this example were achieved using the

Levels tool.

Fig. 11.3.16:

Differential processing of image elements. In this image

the foreground and background were adjusted differentially via the

Levels tool. In addition, parts of the bird’s plumage were

individually

selected and brightened or darkened to give the impression of greater

dynamic range. This is an extremely powerful technique, though it

requires some care and experience to use it most effectively.

I often find that exposure changes that seem to look

good to me during

postprocessing don’t look as good when I come back later after taking a

break from the computer. It’s a good idea to create several

versions

of an image during postprocessing and then come back later with a

refreshed perspective (i.e., fresh eyes) and see which version looks

best. This is easy

to do using the Save As...

menu option; simply save the file using a

new file name each time by affixing a version number to the end (e.g.,

warbler-6.jpg, warbler-7.jpg, etc.).

|

|

|