|

11.6 Sharpening

Probably the most

under-appreciated challenge of digital postprocessing of bird images is

that of sharpening.

Recall that because most DSLR cameras employ an anti-aliasing filter in front of

the imaging sensor, which has a dispersive effect on the pixel

information in the raw image, some degree of artificial sharpening in

postprocess is almost always necessary in order to reclaim the

crispness of the original scene.

When I first started digitally processing bird

images, I never expected the degree of difficulty I would eventually

face in trying to find the ideal sharpening parameters for my

images. One of the problems is that my tastes regarding the ideal

amount of sharpening have changed over time. At first I liked

seeing all of my images with maximal sharpness—probably because I had

become so frustrated with the softness imparted by the optically

inferior lens I was using at the time. In time I became aware

that many of my postprocessed images appeared over-sharpened—a quality that those

with experience in digital imaging can identify almost immediately,

though to novices it’s not always immediately apparent.

Over-sharpened images, more than anything else, carry the stigma of

being the product of an amateur—or,

worse yet, someone lacking any semblance of artistic talent or taste.

As a result, I stopped sharpening my images so

aggressively, and in some cases I over-compensated by leaving my images

too soft. I’ve now realized that there is a very, very delicate

balance between artificial sharpening and natural softness that

produces the most aesthetic images—at least from my perspective.

Sharpness, like any other image aspect, is to a large degree a

subjective quality. For that reason, there are no hard-and-fast

rules that can be followed to always consistently produce the ideal

results. As with any art form, you need to learn to listen to the

intuition embedded in your visual cortex and other primitive brain

centers to aid your rational decision-making during

postprocessing. In this section we’ll consider a number of issues

and general rules-of-thumb that you can use as an initial set of mental

crutches as you refine your sharpening technique.

First, let’s consider the tools at your

disposal. In Photoshop, there are several distinct tools that can

be used to artificially increase the sharpness of an image. The

one I recommend most strongly is the Sharpening

pane in Adobe Camera

Raw (ACR), which is depicted in the figure below.

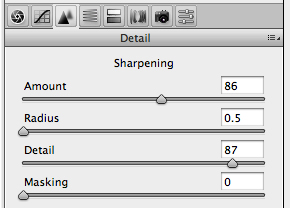

Fig. 11.6.1:

The Sharpening pane of Adobe Camera Raw.

The advantage of sharpening in

Adobe Camera Raw (ACR) is that the sharpening algorithm used by the

software has access to the largest amount of information, since it is

applied directly to the RAW file during conversion to Photoshop’s

internal representation. Keep in mind, however, that the degree

of advantage that you gain from performing sharpening during RAW

conversion (versus doing it later, after conversion, in Photoshop

proper) may very well be camera-dependent, since the process of RAW

conversion is necessarily tailored to the different file formats of

different camera vendors. For my Canon EOS 1D Mark III camera, I

find

that the sharpening effect that I can achieve in ACR is far superior to

what I can achieve later in Photoshop proper (with default ACR

settings), so I try to perform the

bulk of my sharpening in ACR, though I always apply a bit of additional

sharpening later in Photoshop proper, after conversion and resizing of

the image for the specific distribution medium (e.g., web page,

photographic paper, or canvas).

In the above figure you can see that the version of

ACR that I currently use provides four sliders: Amount, Radius, Detail, and Masking. I

always leave Radius at 0.5

and Masking at 0, and then

try to find the

ideal settings for Amount and

Detail. Note

that in some versions

of ACR, the effect of these sharpening sliders is only apparent when

viewing the image at 100% zoom. In my experience, the Detail

slider tends to affect the finest details in the image, and should be

set most aggressively, while the Sharpening

slider needs to be set more

conservatively to avoid artifacts due to over-sharpening.

After setting the sharpening parameters (and any

others in ACR), I then convert the image from RAW and view it in

Photoshop proper. Often I’ll find that the image, after

conversion from

RAW, doesn’t exhibit the ideal amount of sharpening, and I then need to

close the file and re-open it in ACR so that I can change the

sharpening parameters and re-convert from RAW. Though this is an

awkward and inconvenient process, I generally find that it’s more than

worthwhile, since the sharpening tools in Photoshop proper often can’t

reproduce the exact sharpening effect that those in ACR can.

Once I’ve got the image into Photoshop proper and

I’m

more-or-less satisfied with the sharpness of the full-resolution image,

I then reduce the resolution as desired (via the Image

Size window, which I have tied to the Cmd-I key combination on

my computer) and adjust the sharpness of the reduced image using the Unsharp Mask tool of Photoshop,

which is depicated below.

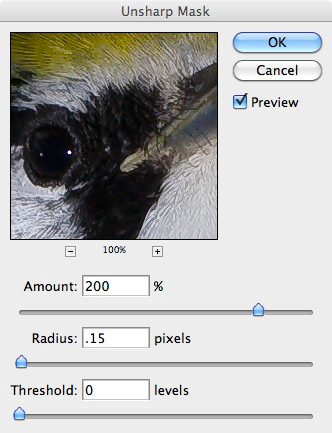

Fig. 11.6.2:

The unshsarp mask in Photoshop.

The Unsharp Mask is by far the

most popular sharpening method in Photoshop. As you can see

above, the tool provides a tiny preview of the image, though with the Preview check-box

checked, the entire image will also act as a preview

(though you should make sure that the image is zoomed to 100% before

using the image preview to assess the effect of sharpening).

The three parameters of the Unsharp Mask are Amount, Radius, and Threshold. For the vast

majority of cases, I set the Threshold

to 0 and

the Radius to 0.15, and then

adjust the Amount slider

until the image looks best to my eye. For my current version of

Photoshop (version CS3), 0.15 is the smallest radius that has any

effect, so it allows me to attend to the smallest possible details in

the image. In some cases I do find that 0.15 results in too many

image artifacts (primarily whitish pixels appearing in the busiest

parts of the bird’s plumage), and will then set it instead to

2.0. On rare occasions I’ll use a radius of 1.0 in conjunction

with an extremely small Amount

setting; this tends to improve the

overall perception of clarity in the bird without over-sharpening the

fine details or introducing halos and other artifacts associated with

over-sharpening. It’s worth experimenting with the Threshold

slider in cases in which you keep getting artifacts whenever you get

close to the amount of sharpening that you think is required. The

Threshold

parameter can sometimes eliminate or reduce those artifacts

without affecting the resulting clarity achieved by the

sharpening. But for the vast majority of post-conversion

sharpening that I do, the Threshold

is set to 0 and the Radius to

0.15,

and I just painstakingly vary the Amount

slider until the image (at

100% zoom) looks good to my eye.

Though the Unsharp Mask is the most popular sharpening

method for serious Photoshop users, there is one other tool that some

people

swear by: Smart Sharpen.

This tool is considerably more

sophisticated than the Unsharp Mask.

First, it allows you to set

separate sharpening parameters for shadow

and highlight regions of the

image. Second, it automatically applies a post-sharpening blur to

help reduce artifacts introduced by the sharpening procedure.

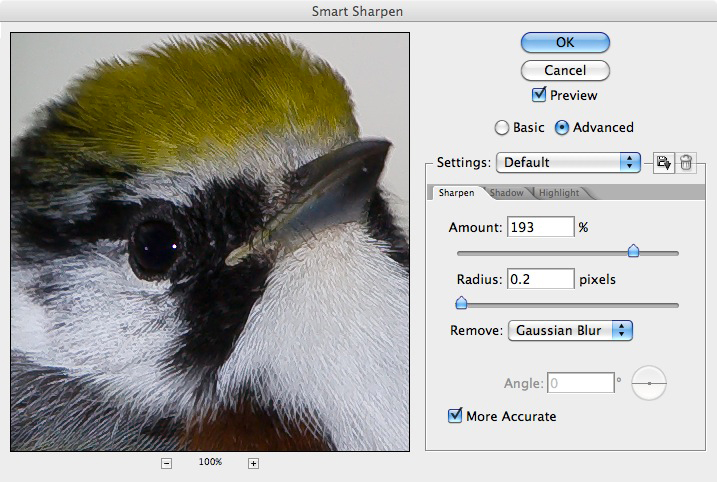

Fig. 11.6.3:

The Smart Sharpen tool in Photoshop.

The Smart Sharpen tool is highly

flexible and undoubtedly very powerful. I’ve personally avoided

using it

because I find that the preview that is rendered in real-time doesn’t

always match the way the image looks after I press the OK button and

commit the changes. I instead find the combination of sharpening

in ACR and fine-tuning later in Photoshop via the Unsharp Mask (after

changing image resolution via the Image

Size tool) to provide all the

flexibility I need. The real challenge is finding the ideal

parameter settings for these respective tools, so as to produce the

most

aesthetically pleasing bird images. The latter goal is what we’ll

concentrate

on for the remainder of this section.

First, we need to note several things. The

issue of monitor-dependence is one of the most important—and most

unfortunate. After upgrading my Apple

laptop to a newer model of

the same line, I noticed that many of my bird photos that looked

tack-sharp on my older laptop no longer looked so nice on the newer

machine. Different computer monitors can differ fairly

substantially not only in the pixel

pitch (the number of pixels per millimeter—or, stated

differently, the size of the individual pixels, in micrometers), but

also in their color fidelity and contrast

ratio. As computer

manufacturers continue to make improvements to their hardware over the

years, newer monitors will inevitably become better and better.

Unfortunately, this doesn’t necessarily mean that your images,

postprocessed on an older monitor, will look better on newer

monitors. Over time you’ll become highly proficient at precisely

optimizing your images so as to look virtually perfect on your

particular computer’s monitor. Just keep in mind that differences

in

rendering technologies will result in your image looking somewhat different (whether

better or worse) on other peoples’ monitors. This is a very

frustrating

aspect of digital imaging, but one that does not seem to have any

practical solution at present. (See section 16.2.4 for a

discussion of the

related issue of gamma

differences between monitors). Note also

that sharpening is highly medium dependent, so don’t assume that the

ideal sharpening for internet distribution of your images will also

serve as the optimal parameterization for printing (see Chapter 14).

Second, it’s important to note at the outset that

the ideal sharpening amount can be highly variable across the

image. In particular, you’ll typically want to sharpen the eye

and beak separately from the rest of the bird, since the eye and beak

are the two most psychologically salient features to human observers of

birds. I generally sharpen the beak more than any other part of

the bird, often setting the Amount

slider to 500% in the Unsharp

Mask. The eye I typically sharpen less than the beak, but

more than any other part of the bird. In both cases (eye and

beak) I generally use a radius of 0.15. Sharpening of the eye and

beak is usually very straightforward. The difficulty generally

arises when trying to find the ideal amount of sharpening of the bird’s

plumage. This will, therefore, be the focus of the rest of this

section. We'll proceed largely by anecdotal illustration, since

this is a highly subjective issue and will necessarily vary in subtle

ways from image to image.

Let’s start by

considering the example illustrated below. For this flycatcher,

the eye and beak appear suitably sharp (the beak could be slightly

sharper, but it’s at least acceptably sharp). What remains is to

assess the sharpness of the bird’s plumage.

Fig. 11.6.4: Flycatcher with a fly.

For this particular example, the overall bird appears suitably

sharpened on my

monitor—though on yours it may appear over-

or under-sharpened,

depending on your monitor’s pixel characteristics. On my monitor

I can just start to discern the individual feather barbs making up the

bird’s plumage, though none of those fine-scaled biological features

show any obvious image artifacts here (on my screen, at least).

The white parts of the

bird’s ventral side show sufficient detail in all areas, indicating

that little or no over-exposure has occurred. The top of the

bird’s head

exhibits some feather glare, possibly due to flash, and there are

a few sharpening artifacts—apparent as whitish pixels that stand out

from the

rest. Take special note also of the wing feathers. They

vary

from sharp to soft, largely as dictated by the depth-of-field (DOF)

induced by

the configuration of the optical system (e.g., the aperture and

distance to subject), and are therefore somewhat natural. The fly

in the

bird’s mouth could, in my opinion, be sharper, as could the bird’s feet.

Continuing in the vein of instruction-by-example,

let’s consider the bay-breasted warbler shown below. The beak

appears suitably sharp, as does the eye. The rest of the head is

less sharp. The bird’s upper back appears quite sharp, and in my

opinion shows very few (if any) sharpening artifacts. The flight

feathers on the left wing show a region of very nice sharpness, though

the DOF is very shallow here, so the tips of those feathers are

suitably blurred. The bird’s right flank looks a bit unnatural to

me, though the number of sharpening artifacts (i.e., unnaturally

whitish pixels) in this region isn’t terribly large. The bright

part of the bird’s dorsal neck (the thin slice of direct sunlight

striking the bird from behind) does appear over-sharpened, showing that

over-sharpening can be exposure-dependent.

Fig. 11.6.5:

Bay-breasted warbler.

For the next

example, a Prothonotary warbler, the sharpest elements are the beak and

the toes. The DOF is again shallow, with the in-focus area

including only the bird’s head and feet, and the perching

substrate. Keep in mind that DOF is a natural phenomenon that

viewers can intuitively relate to, so don’t try to unnaturally sharpen

parts of the bird falling outside the shallow focus area. In the

example below I think the beak is adequately sharpened, and the eye is

probably adequately sharpened as well, though the rest of the bird’s

head (particularly the throat region) could be sharpened slightly

more. In this case the wing coverts could probably have been

sharpened a tiny bit more, since they’re obviously a high-contrast

feature on this bird. Note that sharpening of the intense yellow

regions of this bird can be difficult, since sharpening filters will

tend to produce artifacts (isolated bright pixels) in these types of

cases. Don’t hesitate to select even the smallest regions of the

bird for differential sharpening. Also, recall (from section

11.2) that the Highlights

filter can in many cases be used to bring out subtle details in bright

plumage areas; the Unsharp Mask

isn't the only tool at your disposal in this regard.

Fig. 11.6.6:

Prothonotary warbler.

The image blow is of another Prothonotary

warbler. In this case, a bit a over-sharpening is apparent,

primarily in the back, mid-wing, and flank regions of the bird.

To me, the head and beak look nearly perfect, with no evidence of

over-sharpening. The tail looks likewise quite acceptable

as-is. Notice in this example that the wing comprises a number of

different regions, each with different sharpening needs, due to their

differing positions relative to the focus plane. The nearer parts

of the wing look perfect to me, the middle portions somewhat blurry,

and the distal portions again suitably sharpened.

Fig. 11.6.7:

Prothonotary warbler.

For the Palm

Warbler image below, we’re again faced with an exceptionally shallow

DOF, comprising less than an inch of perfectly in-focus area. The

beak falls somewhat outside this area, and is consequently

less-than-perfectly sharp. The sharpest regions are the throat,

the cheek, the dorsal portion of the head and nape, and the upper

chest. The only parts that strike me as slightly over-sharpened

are the throat (directly beneath the beak) and the nape, which exhibits

some very, very slight artifacts (isolated whitish pixels). The

top of the head could use some more sharpening, in my opinion, possibly

with a large radius and small amount.

Otherwise, the lack of sharpness in the regions of the bird outside the

focus area seem appropriate to me, given the shallow DOF.

Fig. 11.6.8:

Palm warbler.

The next

example again features a palm warbler. In this case the eye and

beak look slightly soft to me, as does the rusty cap, while the bird’s

chest, back, belly, and wing look well-sharpened on my monitor.

To

sharpen up the eye and beak in this example, I’d simply use the Quick

Select tool to select those regions and then open the Unsharp Mask

while those regions are still selected. When there is an active

selection in the image, the Unsharp

Mask affects only those selected

regions (just as with any other filter in Photoshop).

Fig. 11.6.9:

Palm warbler.

For the next example (below) we have a

chestnut-sided warbler. On my

screen the overall sharpness looks fine, though the beak could use a

bit more sharpening. Notice that the white underside of the bird

has a large amount of detail. Much of what you’re seeing in that

white region is actually an artifact of agressive sharpening, in

combination with micro-contrast

induced by flash (see section 7.1). The

local aggregations of

pure white

pixels would, in a non-white part of the bird, create an impression of

over-sharpening, but in the pure white plumage it can sometimes help to

over-sharpen in order to emphasize details that would otherwise go

unnoticed in a sea of almost pure white.

Fig. 11.6.10:

Chestnut-sided warbler

Our next example features a golden-winged warbler

(below). The

only thing that appears under-sharpened on my monitor is this bird’s

eye. The near-white underside of the bird is, in my opinion,

tastefully over-sharpened—meaning that over-sharpening of this

near-white area has brought out details that would be otherwise

difficult to see. In contrast, the bird’s back is just starting

to show some moire artifacts

due to sharpening, and these generally

aren’t aesthetically pleasing. In this case, on my monitor, the

effect is quite tolerable, but if it were sharpened just a tad more it

would probably look offensive to my eyes.

Fig. 11.6.11:

Golden-winged warbler.

For the Baltimore oriole below,

the overall sharpeness looks good on my monitor. The beak and

head feathers are well-defined, though the beak could possibly use just

a tad

more sharpening. Beaks can take quite a lot of sharpening without

looking over-done, certainly more so than feathers. Keep in mind

that all of these images will likely be rendered at a different pixel

pitch on your monitor (unless you happen to have exactly the same

laptop model I’m using), and your assessment of what looks like an

ideal amount of sharpening will likely differ. This is the curse

of media-dependent image qualities (of which sharpness is just one).

Fig. 11.6.12:

Baltimore Oriole.

Continuing on to the next example image, the female

yellow warbler

below looks slightly soft to me in her eye, while some moire patterning

in the bird’s back feathers suggests over-sharpening. Moire is,

of course, a natural phenomenon that you can perceive even when viewing

the bird with your naked eyes, and is especially prevalent in certain

types of feather patterns. The difficulty is to try to both avoid

creating unnatural moire patterns and to also avoid exacerbating

natural

moire patterns into what many viewers will perceive as sharpening

artifacts (whether they are or not). This simply requires

experimentation with different sharpening levels as applied to the

specific part of the bird that is most moire-prone.

Fig. 11.6.13:

Female yellow warbler.

The next example (below) again

illustrates the value of aggressive sharpening in white plumage.

Though this bird’s underside is arguably not over-sharpened, a bit of

over-sharpening might actually help to further emphasize the detail

present in that vast white region. Regarding the rest of the

bird, I find the lower wing feathers to be appropriately sharp, the

upper wing feathers to be appropriately soft, and the face (including

the eye) to also be appropriately soft. The eye, which appears

remarkably three-dimensional in this image, could probably bear

additional sharpening, but in this case I think it has enough

definition to stand as-is. Though the beak could be sharper, its

slight softness matches that of the rest of the face. Remember

that modern viewers are aware (even if subconsiously) of the issue of

depth-of-field (DOF), so when your DOF is razor-thin, some softness in

the out-of-DOF regions are not only acceptable but indeed

expected. To the extent that you may be striving for a true “photographic” look (rather than an artificial, “painted” effect), your sharpening strategy

should respect any apparent DOF in the image. For more abstract

works, however, such constraints can be largely set aside.

Fig. 11.6.14:

Tree swallow.

The vireo image below illustrates

the value of softness (as opposed to sharpness) for certain

images. To my mind, vireos appear naturally soft, and for that

reason I’ve left much of the bird under-sharpened (especially parts of

the bird below the head). A slight suggestion of moire is still

present, however, in the visible portion of the bird’s back and in its

cap. The beak and eye appear appropriately soft for this

image. Over-sharpening of the white underside has not been

applied, in agreement with the overall soft theme of this image.

The bird’s feet and the branch it’s perched on could use more

sharpening, however.

Fig. 11.6.15:

Vireo.

In contrast to the image above,

the red-eyed vireo in the image below exhibits some obvious sharpening

artifacts (as well as a bit of over-flash in the face and neck).

Moire is clearly present in the cap. The eye is quite sharp,

though the beak unfortunately falls somewhat out of the DOF and

therefore appears soft. Some moire is apparent in the bird’s back

and in the wing coverts. A bit of over-sharpening is also

apparent in the part of the bird’s head starting at the right cheek and

extending around toward the back of the head. Though the perfect

sharpness of the eye may appear a bit unnatural if you look too closely

at it, the extreme sharpness helps to focus the viewer’s attention on

the most salient aspect of the creature, and to establish the center of

the DOF.

Fig. 11.6.16:

Red-eyed Vireo.

For the next vireo (below), we’ve

again opted for an overall soft look, though a number of sharpening

artifacts are nonetheless present. The white pixels in the bird’s

belly are just slightly over-sharpened: they create the impression of

excessive flash in that part of the bird. The flight feathers

appear appropriately soft on my monitor, and the primary and secondary

coverts seem slightly soft, but consistent with the overall theme of

the image. Moire is clearly present, however, in the bird’s back,

and some over-sharpening is apparent in the bird’s cap. The beak

is appropriately soft for the image. The tail looks a bit too

soft to me.

Fig. 11.6.17:

Red-eyed Vireo.

As one final example, the

chestnust-sided warbler below combines tasteful softness in the wings

with moderate over-sharpening in the white ventral regions to create an

image featuring a range of textures. I’d personally prefer to see

the white ventral region slightly less over-sharpened.

Fig. 11.6.18:

Chestnut-sided warbler.

One trick that

may help you in finding the right sharpening parameters is to first

duplicate the bird layer, apply fairly aggressive sharpening to that

duplicate layer, and then decrease the layer opacity in the Layers panel. Sometimes

exploring different opacities of the sharpened version of the layer

makes it easier to make up your mind about how much sharpening you

want. In some cases you may also be able to achieve an effect

that direct sharpening can’t give you, since sharpening artifacts can

be softened by the blending of the sharpened layer with the unsharpened

layer. I find that this approach often seems to make the effect

of the sharpening more subtle, so that the bird looks sharp without looking artificially sharpened. A related

technique is to subject the duplicated layer to a high pass filter (Filter > Other > High Pass)

with a radius of 0.5, and then to set the layer's blend mode to Overlay or Soft/Hard/Vivid Light, with an

appropriate opacity.

Occasionally

you’ll find that no matter what sharpening parameters you try, the

final product never looks right to you, even when the original photo

lacked any obvious motion blur or focus problems. One thing you

can try is to apply the sharpening and then to reduce contrast slightly

via the Brightness/Contrast

tool. Though sharpening works by increasing local contrast, it sometimes

results in an apparent increase of contrast at a courser scale, which

the Brightness/Contrast tool

can rectify by dialing in -5 or -10 for the Contrast slider. In rare

cases you might also find that adjusting saturation a tiny bit can

alter your perception of the effect of a previously-applied sharpening

pass. Remember also that noise reduction and sharpening (in

either order) can interact to create an effect that looks better or

worse, depending on the image and the chosen sharpening or denoising

parameters.

|

|

|