|

12.2

Structuring Your Archive

Before we delve into the details

of workflow-based image processing, let’s take a moment to consider an

important topic that tends to be overlooked, but that can have a

significant impact on your workflow—namely, how to optimally structure

your rapidly-growing collection of digital image files. As you’ve

no doubt already noticed, collections of digital images tend to grow

very rapidly, and can easily become a dense, unmanagable mess.

The critical issue here is how to efficiently find what you’re looking

for in that mess, when the need arises—i.e., how to find the proverbial

needle in a haystack.

As it turns out, this very issue has been subjected

to intense academic investigation over the past few decades, primarily

in the field of information retrieval.

Unfortunately, the science of information retrieval, as applied to

digital images, has advanced rather more slowly than the other areas of

that field. The problem is that computers really aren’t very good

at figuring out what an image file actually depicts—i.e., whether it’s an image

of a golden-winged warbler at dawn, or of the Eiffel tower at

dusk. For all intents and purposes (i.e., in the absence of

carefully curated databases and highly trained classification

algorithms), the computer has no idea what the image contains.

Thus, to make automated searching for particular

images in your growing archive feasible, you’re going to have to tell

the computer what each image contains: whether a blackbird clinging to

a cattail, an osprey feeding bits of fish to its offspring, or an

ostrich with its head in the sand. The simplest way to do this is

to indicate the photo’s semantic content via the image’s

filename. For example, an image showing a juvenile osprey

exercising its flight muscles in the nest might be called osprey-chick-flapping.jpg. In

all likelihood, if you’ve got one such image, then you’ve probably got

many, so you’ll want to number them—e.g., osprey-chick-flapping-47.jpg.

The idea is simply to spell out in the filename what the image

shows. The purpose of doing so is to allow the computer’s

automated file searching tools to find the images that satisfy whatever

criteria you give them. You might, for example, search for all

photos depicting ospreys, or all photos depicting osprey chicks, or all

photos depicting osprey chicks flapping their wings. When

choosing a filename for an image, you really need to think about the

types of automated searches you might perform in the future; your

ability to find particular photos later will depend on how well you’ve crafted their names.

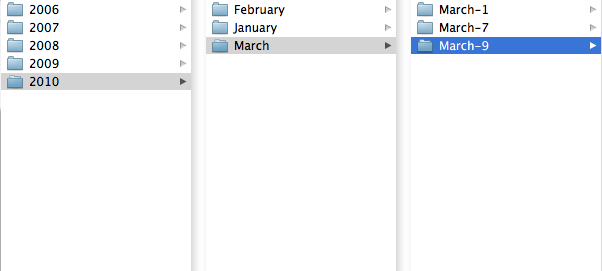

Fig. 12.2.1:

Most operating systems have a search tool

that allows you to find files based on their filenames.

If you make a habit of putting the species name (and

possibly other relevant information) in the filenames of

your images, your archive will be more easily searchable.

Assigning an informative filename can be done very

conveniently when saving the postprocessed version of an image.

Photoshop will prompt you for a filename anyway (since you can’t save

changes back to the RAW file), so that’s a good time to choose a name

that will be informative. Since you’ve just finished

postprocessing the image, you’ll know at that time what species of bird

is depicted in the scene. I recommend using a filename of the

form:

species - RAWID . ext

where species would be

something like “great-blue-heron”, RAWID would be the base filename

assigned to the RAW file by the camera (i.e., something like 7D1E4233 or the like), and ext would be PSD, JPG, or TIFF,

depending on the type of file you’re saving (PSD files are native

Photoshop files that contain layers, saved selections, text elements,

etc.). The advantage of this filename convention is that the

species part (which might also include descriptive words such as “flying” or “eating”) can be searched easily, while

the RAWID portion of the filename allows you to connect the processed

JPG file to the original RAW file if necessary (for example, if the

original JPG is a low-resolution version for display on a web page, and

you decide later to re-process the RAW file to produce a printable

high-resolution JPG or TIFF for publication).

If your JPG files retain EXIF

information, you can also use specialized search tools, such as the Find function in Adobe Bridge,

that allow you to search for files based on the equipment settings used

for the photo, such as ISO and focal length (see the figure

below). EXIF data is stored in both the RAW files and the JPG

files that are produced by the camera. In post-processing, if you

save a RAW photo from Photoshop into a JPG file, that JPG file will

also retain the EXIF data. Note, however, if you perform screen-scraping—using a

pixel-capture utility to copy the image directly from the screen into a

file—the EXIF data won’t be copied to the new file.

Screen-scraping is sometimes useful for non-Photoshop image-processing

applications, since some of those applications don’t show you an exact WYSIWYG (What You See is What You Get)

representation of the file on screen; that is, the file saved by the

application may not look exactly like what you see on-screen when

editing the image. Once you get the on-screen image looking the

way you like it, screen-scraping that image directly to a file using a

separate pixel-copying utility will ensure that the saved file looks

exactly like what you saw on the screen. If you’re using

Photoshop, however, this shouldn’t be necessary (though you may need to

adjust the setting under View >

Proof Setup for your monitor). Exporting a JPG directly

from Photoshop should produce a WYSIWYG file, which will also retain

EXIF information. The EXIF information contains just about

everything you’d want to know about the technical details of the image:

the shutter speed, aperture, focal length, flash power, exposure

compensation level, etc.

Fig. 12.2.2:

Some tools, like Adobe Bridge, allow you to search

through your RAW files based on EXIF features such as focal

length, ISO setting, etc.

The next thing to consider is how to choose a directory structure for organizing

your files. Keeping different sets of files in different

subdirectories allows you to zero in on the particular files you’re

looking for faster. Some options are to create separate

directories for individual bird species, or for different shooting

locations, or by the date the photos were taken. I prefer the

latter option. As illustrated in the figure below, my archive is

organized by year at the top level, then by month within each year, and

then by day within each month.

Fig. 12.2.3: An

archive structure based on date. If you know roughly

when you took the photo you’re looking for, you can perform a directed

search based on the date. This structure has minimal maintenance

requirements: whenever you upload photos from a memory card, you

simply create a new directory with today’s date. That’s ideal for

large

numbers of RAW files. For your postprocessed JPG files, a

better

structure might be based on taxonomic classification or location.

The main

advantage of this type of organization is that adding new photos

requires the minimal amount of time and effort. When I return

home from the field, I simply create a new folder with today’s date,

and then download all my memory cards into that directory. (I

also backup the new directory to two external hard drives).

Although organizing my directory structure by species would make

searching later easier, I rarely have enough time to sort through all

the photos I’ve taken each day and move them to the appropriate

directories. However, during post-processing (which sometimes

doesn’t happen till months after the photos were taken), I can put the

species name in the filename of the processed JPG file, which allows

searching by species using a search tool such as Adobe Bridge or the Spotlight tool in Mac OS X.

In addition to my vast archive of RAW files, I also keep a

separate, much smaller archive of post-processed JPG files. When

searching for images of a particular species, I can then search the

smaller JPG archive, and then when I’ve chosen the handful of JPG files

I’m interested in, I can track those back to the corresponding RAW

files in my RAW archive (based on the capture date in the EXIF).

Because my JPG archive is separate from my RAW archive, I can structure

it differently. In particular, I can create specialized

subdirectories for various purposes—e.g., for individual species, or

for files that have been optimized for printing on a particular medium,

or for photos taken during a particular birding trip, etc.

Because there are far fewer post-processed images than RAW files in my

archives, I can more easily find the time to organize the JPG’s into a

thematic directory structure. Note that in some operating systems

you can also create links or shortcut files that allow one file

to appear simultaneously in multiple directories (without wasting space

by actually duplicating the file). This is useful for when a

photo naturally belongs to multiple categories—e.g., both the “Great Blue Heron” category and the “Photos from My Florida Trip” category.

At some point, your archive will almost certainly

become so big that it no longer fits on your computer’s hard

drive. I now keep my archive on external hard drives rather than

on my computer’s internal hard drive. When the external drive

becomes full, I simply buy another external drive and put the newer

images on the new drive. I keep two identical copies of each

drive (for a total of three copies), for backup purposes, and I keep

those copies in different physical locations: one at home, one at work,

and one in a safe-deposit box at my bank. I’ve learned the hard way that hard

drive failures are extremely common.

In terms of the file formats for post-processed

images, I use JPG because it’s more space-efficient than TIFF.

Sometimes I need to generate a TIFF version for publication, and in

those cases I either convert the JPG file directly to TIFF (in

Photoshop), or go back to the original RAW file and post-process it

from scratch into TIFF (i.e., if I think that doing so will produce

more detail in the resulting TIFF than was present in the JPG).

Remember that the images you post-process for posting on your web page

or sending to friends via email will generally be much too small (i..e,

be of insufficient resolution) for printing or publication. This

is why you should always retain your RAW files in case you need to

later re-process them to produce a higher-resolution image.

Finally, note that there are commercial database

applications that can be used to manage your photos. I generally

don’t recommend these, since they tend to tie you to a particular

operating system (or even a particular version of the operating sytem),

and in some cases they may be prone to losing images via corruption of

the database.

|

|

|