|

13.4 Simulating

Motion Blur

Although motion blur is typically

undesirable in bird photography, it can sometimes enhance rather than

mar an image, especially if it affects only part of the scene, such as

a hummingbird’s wings. For birds in flight, if the background is

too busy for your tastes, you might consider adding some motion blur to

the background to strengthen the perception that the bird is

moving. This is the application that we’ll consider in this

section.

The figure below shows a male osprey hurrying back

to to the nest with a meal for the family. To reinforce the

impression of urgency and great speed, we’ll apply the Motion Blur

filter in Photoshop to the background; the impression we’re trying to

create is that while the viewer maintains focus on the bird, the scene

is passing by in a blur.

Fig.

13.4.1: Male osprey on his way back to the nest with yummy

victuals. Because the

camera was following the bird, the background was in motion, and is

thus slightly blurred.

The Filter > Blur > Motion Blur effect in Photoshop can be used

to exaggerate this effect.

As usual, the first step is to separate the bird

from the background, via the use of layers. In this case we used

the Quick Selection tool to

quickly select the bird, and then used Select

> Inverse to invert the selection so as to include the

background instead

of the bird. Pressing Cmd-J /

Ctrl-J then copies the background

into a new layer. (We could instead have duplicated the entire

image and then used the background selection to initialize a layer

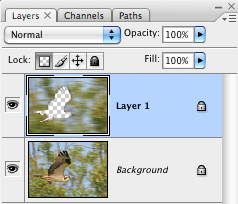

mask). The resulting Layers

panel is shown below. Note that

we’ve locked the transparent pixels in the top layer by clicking on the

checkerboard icon next to the “Lock” label.

Fig.

13.4.2: The Layers panel after

Fig.

13.4.2: The Layers panel after

creating a background layer. The bird

has clearly been omitted from the

background layer. We could also have

left the bird in the background layer

and then masked it out using a layer

mask.

We then invoke the Filter

> Blur > Motion Blur

filter while the background layer is active (the blue highlighting in

the above figure indicates which layer is active). The figure

below depicts the Motion Blur

tool. Then Angle

setting was left

at 0 since the bird is flying horizontally. The trick is then to

find a Distance value that

conveys the desired sense of speed.

With the Preview box checked,

changes to this slider should appear

instantaneously on your screen so you can judge the aesthetics of the

effect.

Fig.

13.4.3: The Motion Blur tool in Photoshop allows you

to indicate an angle and degree of blurring (“Distance”).

While the angle obviously needs to match the direction of

movement, the Distance setting allows some flexibility in

achieving the desired artistic effect.

The figure below shows the final image, after

application of the blur filter. Note several things about this

image. First, the blurring of the background not only conveys the

notion of movement and speed, but also reduces the detail in the

background and thus helps to make the bird stand out more.

Second, note the dark shadow that extends a short distance left and

right of the bird. This is an artifact of the blur filter that

arises because of an imprecise selection when creating the background

layer. The problem is that some of the darker pixels from the

bird were inadvertently included in the background selection; the blur

filter smeared these darker pixels out around the bird, resulting in

the shadow.

Fig.

13.4.4: The result of applying Motion Blur to the background.

Note the shadow apparent to the left and right of the bird. This

is

an artifact resulting from sloppy selection prior to creating the

background layer. Expanding or contracting the selection prior

to creating the layer can mitigate these effects, though if taken

too far you can induce other unpleasant artifacts (e.g., an

obvious margin around the bird that lacks any blurring).

The leftmost image in the figure below illustrates a

more extreme case of this. Upon noticing this effect, the History

tool (section 10.5) was used to back up to an

earlier state of

processing, and then the foreground selection was expanded by 2 pixels

via Select > Modify > Expand.

The foregoing procedure was

then repeated: the selection was inverted, the background was

duplicated into a separate layer, transparent pixels were locked, and

the blur filter was applied. (The reason we expanded the

foreground selection rather than contracting the background selection

was to avoid edge artifacts around the outer margin of the image;

because of edge effects, expanding one selection is not always the

same as contracting its inverse selection). The rightmost image

in the figure below shows the result. The shadow effect has been

substantially reduced, due to the inclusion of fewer dark pixels from

the bird in the background selection. Further improvement could

be achieved using either a larger expansion radius or by manually

adjusting the selection boundary using the Quick Selection (or other) tool.

Fig.

13.4.5: Mitigating blur artifacts by adjusting the selection.

Left: dark pixels from the bird that were included in the background

selection resulted in dark smearing around the bird. Right:

expanding

the foreground selection prior to inverting it reduced the shadow effect

by allowing fewer stray pixels from the bird to fall within the

background

selection.

The next figure (below) illustrates the importance

of locking the transparent pixels before applying the blur

filter. The left image shows what happens when the transparent

pixels are not locked: the blurring has extended into parts of the

image occupied by the bird, resulting in loss of foreground detail, and

even the impression of a fog in front of the bird. There may

indeed be cases in which such an effect may be desirable in achieving a

particular artistic goal, so it’s often worthwhile to try multiple

settings of each parameter or button in a filter’s interface before

settling on a final setting.

Fig.

13.4.6: The importance of locking transparent pixels prior to blurring.

Left: blurring the background layer without first locking transparent

pixels

results in a haze over the bird. Right: locking the transparent

pixels ensures

that the output of the blur filter can’t intrude into the area occupied

by the bird.

As we’ve already remarked too many times in this

book, post-processing operations that dramatically alter reality in

this way will be found objectionable by some people; as long as you

don’t misrepresent your processed images by implying that they are

unaltered photographs, there is no reason why you should feel ashamed

to take advantage of digital tools to achieve an artistic rendering of

a bird and the scene it’s depicted in.

|

|

|