|

3.8 Bells and

Whistles

There are a few other useful

features that some lenses offer, which you may want to take into

consideration when shopping for a birding lens. Just keep in mind

that these are far less important than the basic lens parameters that

we’ve already discussed: focal length, maximum aperture, and overall

image quality.

3.8.1

Full-time Manual Override

Most lenses have a switch that

turns autofocus on and off. If you find that autofocus doesn’t

work well for the shot you’re trying to take (for example, if there’s a

stick in front of part of the bird), then you have to flip that switch

on the lens before manually focusing. Some newer lenses feature a

full-time manual override

mechanism, which means that you can adjust the focus manually any time

you want, without first flipping the manual/AF switch on the

lens. This is only useful in one-shot mode, after the camera has

finished autofocusing, and while you still have your finger on the

shutter-release button. At this point you can manually adjust the

focus and then press the shutter-release button the rest of the way to

take the photo. Note that if you manually adjust the focus before

pressing the shutter-release button halfway, then the autofocus will

still kick in (if you haven’t disabled it via the switch on the lens)

when you press the shutter-release button, which usually isn’t what you

want. The product literature for lenses having full-time manual

override make it sound like an indispensible feature, but in truth I

rarely use it.

3.8.2

Range Limiter Switches

A more useful feature is the range

limiter switch, which many of the cheaper lenses don’t have, and even

on the more expensive lenses it’s often not implemented as well as it

could be. This is a switch that allows you to limit the lens’

focus capability to a range of distances. If you’re at a birding

location in which all the bird are far away, you may be able to improve

the autofocus acquisition speed by limiting the lens so as to focus

only subjects at a distance. Conversely, if all the birds are

very close, you may improve AF speed by limiting the lens to only focus

on nearby subjects. The limiter switch typically has a threshold

distance, N, which might be

20 or 30 feet or so, and may allow you to limit the lens to focus only

at distances greater than N

feet, or less than N feet, or

to allow focusing at any distance (i.e., limiting disabled).

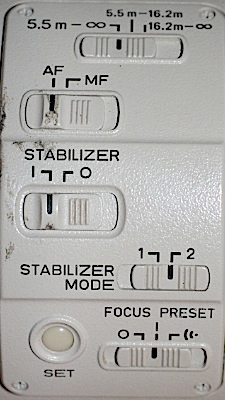

In the figure below is the control panel for a Canon

600mm lens. The top switch is the focus limiter switch. The

leftmost setting disables the limiter, so that the lens can focus at

any distance. This is the setting that I use 99.9% of the

time. The middle setting allows you to focus only on subjects

between 5.5 and 16.2 meters away from the lens, and the rightmost

setting permits focusing only on subjects further than 16 meters.

Fig. 3.8.1: The

control panel of the Canon 600mm f/4L IS lens.

The focus limiter switch is at top. Below that is the autofocus

switch (this lens has full-time manual override), then the switch

to disable image stabilization and a switch for stabilizer mode

(mode 2 is panning mode). I never use the focus preset (it

accidentally got turned on for this photo).

The way the

limiter improves AF speed is to keep the lens from from racking in and

out over its entire focus range when the camera has lost focus.

Recall from section 2.6 that SLR cameras use a

trick to quickly

determine exactly how much the lens’ focusing element has to be

adjusted, and in which direction, in order to bring a subject

immediately into focus. For subjects with poor contrast, however,

this system fails. It can also fail if the current setting of the

lens’ focusing element is far from where it needs to be in order for

the subject to be in focus. In either case, the camera will

typically rack the lens’ focusing element in and out over its full

range, searching for a high-contrast subject to focus on. For

some lenses this can be a very slow process. By limiting the

lens’ focusing range, you can speed up this process, since the camera

has a reduced range to search through in order to find the

subject. If you’ve already got the bird almost in focus, however,

the camera should be able to adjust the focusing element without

racking (though somethings it does anyway, especially in low light, and

especially for cameras will poor AF), and then the limiter switch will

have no effect on AF speed.

In practice, I rarely use this feature, because I

always forget to turn limiting off after I move on to the next

bird. If the next bird is outside the focus range I’ve set on the

limiter switch, then the lens won’t be able to focus on that next

bird. It may take a moment then to realize why the camera isn’t

focusing on the bird, and by the time you realize the problem and

change the setting on the limiter switch, the bird may be gone.

For that reason, I only use the limiter switch in very challenging

lighting conditions, where the AF system is having trouble finding the

bird and hence doing a lot of racking.

3.8.3

Lens Hoods

A very simple, but very useful,

lens feature is the lens hood. Most super-telephoto lenses (i.e.,

those with focal length of 300mm or more) have them. The hood is

the part of the lens beyond the last glass element (the objective lens

element). It shields the lens from the direct rays of the

sunlight that can cause glare and reduce image contrast.

Fig. 3.8.2:

Canon 400mm f/4 lens with (left) and

without (right) lens hood attached. The lens hood

protects the objective lens element (glass visible in

image on the right) from glare and from damage

in the field.

In the figure above is shown a 400mm f/4

lens with and without the lens hood attached. As you can see, the

lens looks much less impressive without the hood, and indeed most

people don’t realize that about a third of this lens (with the hood

attached) is empty. A nice, long hood like this is very effective

at reducing glare, and also helps to protect the lens itself.

With the hood in place, the objective lens element is far less likely

to come into contact with tree branches or other objects that may

scratch the lens. Also, if you drop the lens, there’s a

possibility that it will land on the lens hood, which may prevent

damage to the lens itself.

Not all lens hoods are removable like the one shown

above. Removable hoods are good for cleaning, since it’s easier

to get at the glass to clean it with the hood removed. However, I

never leave the hood off in the field; only during cleaning of the

lens. Note also that lens hoods for expensive lenses are

themselves typically expensive, so it’s a good idea to take care of

them.

|

|

|