|

5.2 Choosing a

Monitor

If you decide to use a desktop

rather than a laptop, you’ll obviously

need to buy a monitor to go with your computer, and in fact even if you

do opt to use a laptop, you may want to buy a monitor to use with your

laptop (especially if your laptop has a small screen). Large,

bright, flat-panel monitors have become extremely affordable in recent

years, and the use of widescreen monitors can be especially convenient

when processing high-resolution images, since the added “real estate”

of the larger monitor will allow you to view larger portions of the

(zoomed-in) image at one time, while also leaving room on the screen

for other information, such as the image’s histogram and the software’s tool palettes.

5.2.1

Monitor Sizes

Whereas most laptops have a built-in screen of only about 15 inches

(measured diagonally between opposite corners), affordable external

monitors now range up to 30 (diagonal) inches or more. As

mentioned above, such enormous screens are a joy to use when editing

images, since you end up

spending less time scrolling back

and forth between parts of an image. Given the amount of time

some of us spend in front of a computer, anything that can make the

process go faster is a godsend. However, it’s important to keep

in mind, when shopping for a monitor, that any model which is both

extremely large and inexplicably cheap is probably inferior in some

other way—i.e., in the pixel pitch

(the size of individual pixels on

the screen), the color rendition, or perhaps the overall construction

and tendency toward component failure. As with cameras and

lenses, it’s usually wise to stick to the name brands when possible

(such as Samsung or Sony),

and to keep in mind that you get what you pay for.

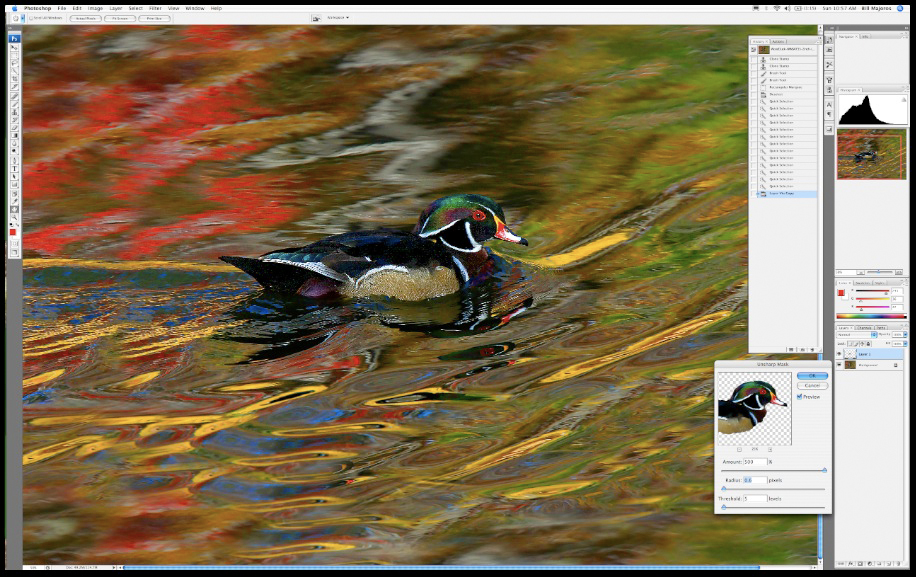

Fig. 5.2.1:

Life on the Big Screen. A 30-inch monitor provides a truly vast

amount of visual

real-estate. With such a large portion of your image visible in

the same window, relatively

little time is spent scrolling back and forth between critical parts of

an image during intensive

editing. This will become even more important as the megapixel

race continues and images

with 30 million pixels or more have to be inspected and/or edited for

publication.

5.2.2

Color Gamut

The color gamut of a monitor

is the largest range of colors that it

is capable of displaying at one time. A limited

gamut can result in a loss of subtle details in largely monochromatic

parts of an image. Laptop

displays typically have a smaller color gamut than quality external

displays, and this can, unfortunately, affect the way you process your

images. Using such reduced-gamut devices can mislead you

into thinking that an image lacks details in particular regions, when

in fact there may be details there which your monitor is incapable of

rendering. Conversely, if your monitor has a large color gamut

but

your printer does not, you may find that an impressively detailed

image, as it appears on your monitor, does not appear quite so

impressive when printed on your consumer-grade printer, since fine

color differences used to represent some of the details in the image

may not come through as distinct details in the printed image.

Also, other people viewing your images over the internet may see less

detail in your images than you see when you view them on your

larger-gamut monitor (or vice-versa).

5.2.3

Pixel Technologies

There are several different technologies in use today by manufacturers

of flat-panel monitors, with different technologies being favored by

different users, depending on whether they prefer better color or better response time. The cheapest

flat-screens use a technology known cryptically as TN, and though these are popular

among the video-game crowd due to their fast response time, they have

significantly lower color fidelity. Indeed, when shopping for a

wide-screen monitor, it may be best to avoid those monitors with the

fastest advertised response times, since these are likely to be TN

monitors (and since faster response times are essentially useless for

static image processing). Several technologies producing higher

image quality are those currently known as IPS (sometimes called S-IPS) and VA (also called PVA or MVA). Unfortunately, these

acronyms rarely appear on product display cards in stores, though some

clever Googling (e.g., including the model number and the letters "TN"

or "IPS" or "PVA" as separate search terms) can often lead to reliable

information on the underlying pixel technology utilized by a particular

model.

In terms of other advertised features of monitors,

such as the viewing angle and

the contrast ratio, some are

likely of greater utility in image processing than others. The

viewing angles of just about all of today’s newest flat-panel monitors

are more than adequate for the single user sitting directly in front of

the monitor. The contrast ratio is likely of greater concern,

though again, the technologies used in flat-panel construction seem to

have reached the point where contrast ratios are quite adequate for

most models (with the possible exception of the cheaper TN models).

5.2.4

Monitor Calibration

Whichever monitor you choose, please

make sure you properly calibrate it before you begin postprocessing

your photos on it! If by chance your uncalibrated monitor has any

sort of bias—whether a color cast or an excess

of brightness or darkness—then you will inevitably end up

compensating for that bias during postprocessing, probably

unconsciously. As a result, your photos will end up having the opposite bias when viewed by others

on their screens. For example, suppose that your uncalibrated

monitor renders images darker than it should. When processing

your photos in photoshop, you’ll have a tendency to over-brighten your

images, to overcome the dark bias of your uncalibrated monitor.

When you post these images on the internet, other people viewing your

images with a properly calibrated monitor will think your images are too bright. You don’t want

that. Calibrate your monitor as soon as you get it, so that you

can be sure that other people viewing your photos on the internet are

probably seeing roughly the same image that you’re seeing on your

monitor. (Of course, those internet viewers won’t all be using

properly calibrated monitors, but many of them will, and on average the

uncalibrated viewers will be most satisfied—on average—by images that were postprocessed

to look well on an unbiased monitor).

You can do a quick check of your monitor’s

calibration status using the calibration key below. If any of the

gray bars have a color cast, or if you don’t see all 10 bars as having

distinct shades (particularly the two darkest bars and the two whitest

bars), then you definitely need to calibrate your monitor. More

subtle biases require specialized software and/or hardware to

detect. Monitor calibration is discussed in section 14.1.2.

Fig. 5.2.2:

Calibration key. This simple strip of

gray bars can be used to diagnose obvious biases

in your monitor’s calibration, but for the best results

you really need to use calibration software to fine-

tune your system. See section 14.1.2.

|

|

|