Chapter

8

Field

Techniques

In this chapter we’ll

go beyond

the technological aspects of camera and flash operation (covered in the

preceding two chapters) and focus on some of the more practical issues

related to shooting in the field. We’ll cover composition principles (i.e., where

you place the bird within the frame), the capturing of interesting

poses, and how to use angles and lighting to your advantage.

We’ll also consider some of the more “physical” aspects of field work, including

how to get close to your subject, how to keep the camera steady while

tracking the bird, and how to deal with difficult situations such as

rain and mud.

8.1 General

Composition Principles

Photographers—even those who

photograph things other than birds—often talk about “composing” an image. Such language

implies, of course, that components of an image can, in some manner, be

assembled at will into a pleasing whole. In the controlled

setting of a portrait photographer’s private studio, this may well be a

viable proposition. In the field, however, with the bird making

its own decisions about whether or not it will assume a pleasing pose

in front of one background or another, the notion of “composing the image” may seem a bit ridiculous.

Nevertheless, there’s typically quite a lot you can

do to influence the overall composition of an impending

exposure—perhaps a lot more than you realize. We’ll start with

the position of the bird in the frame—something you can often dictate

very simply by changing the imaging angle a few tenths of a degree in

the horizontal or vertical directions. By slightly changing the

position of the bird in the frame, you can drastically alter the

viewer’s impression of the world

that the bird lives in. Keep in mind that a person seeing

your photo for the first time likely knows little or nothing about the

precise environment in which that bird was photographed. What

you’re showing him or her is a tiny window on the bird’s world.

From that tiny window he or she then has to imagine what else that

world contains. How you craft the contents of that window can

drastically affect how that viewer’s imaginings proceed from

there. That’s the power of creative photography.

These types of considerations have long been at the

forefront of artists’ minds—indeed, far longer than photography has

existed as an art form. Many great minds have considered the

problem of artistic composition—whether in oils, inks, or other

media—and a handful of useful “rules of thumb” have emerged which can help the

novice to gain a head start on producing more inspirational images.

The most well-known of these guidelines is the

so-called rule of thirds.

While this very crude heuristic has definite merit as a pedagogic

device, we’ll see at length that it has some clear limitations.

Nevertheless, it’ll be worthwhile to spend some time exploring the

applicability of this “rule”.

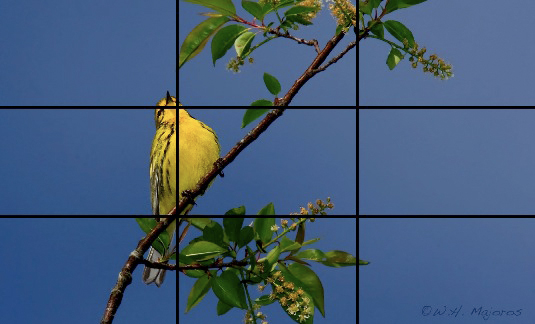

Consider the burrowing owl photo below. The

frame has been partitioned into nine equal areas, by dividing both the

horizontal and vertical axes into thirds.

Fig. 8.1.1 :

The rule of thirds. After partitioning the horizontal and

vertical axes

into thirds, the rule of thirds states that you should try to orient

important

components of the scene so as to lie along a division line, or to fall

on an

intersection of two division lines (a so-called “power point”).

Just keep in

mind that it’s only a rule of thumb—and that no rule in art is

inviolate.

The idea behind the rule of thirds is that major compositional features

of an image should, to the extent possible, align with the imaginary

vertical or horizontal lines that divide the image’s axes into thirds. The

intersections of these lines are known as power points, and are preferred

locations for important subject features. In the case of birds,

at a very course level we might try to align the bird’s vertical body

axis with one of the two vertical lines. In the image above, I’ve

managed to frame the bird in such a way that the bird’s eye almost

perfectly coincides with one of the “power points” (intersection of two guide

lines).

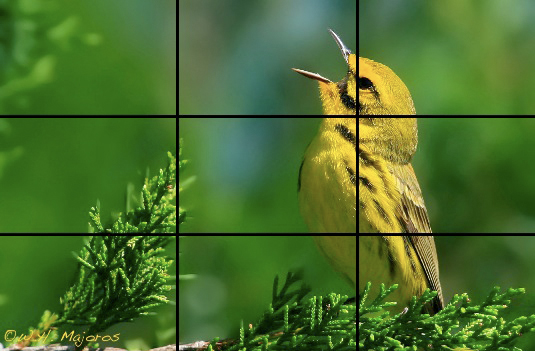

The hawk image below similarly aligns the bird’s eye

with one of the four power points:

Fig. 8.1.2 :

Positioning the bird’s eye on a power point. When the bird

fills this much of the frame, basic constraints such as having a margin

around the bird and giving the bird some space to gaze into can trump

more idealistic considerations.

Note from these two examples that

birds at different distances will generally fill different proportions

of the imaging frame, and that this has implications for the relative

positioning of both major body axes and detailed body features (such as

the eyes, which are typically the most important part of the bird, in

terms of visual and psychological impact). Although it may be

satisfyingly simple

to propose that all birds’ eyes should be positioned at one of the

so-called “power points” implied by the rule of thirds,

the stubborn truth is that the rest of the bird’s body typically

imposes constraints on the image composition that, while often of

lesser rank than that of the positioning of the bird’s eye in frame,

still influence the overall notion of compositional “optimality”. (There’s also the question of just how “powerful” these power points really

are. We’ll get to that later.)

The image below illustrates some of these

issues. Though the eye has been placed some distance from the

nearest power point, the bird’s vertical axis is roughly co-axial with

a vertical division line. Note that the bird is also roughly

bounded above and below by the two horizontal division lines.

Whether this is significant is subject to interpretation. The

greenery is largely confined to the top center rectangle and the bottom

center rectangle, lending some more symmetry to the image. The

fact that the branch’s endpoints don’t both coincide with a division

line works against the overall symmetry somewhat, but composing an

image almost always involves some sort of compromise. Personally,

I think I could have shifted the entire image slightly to the right.

Fig. 8.1.3 :

The rule of thirds may apply in a number of ways.

This bird’s height is roughly one-third of the frame, the greenery

fits (almost) into two of the nine cells, and the bird’s vertical

axis aligns fairly well with one of the division lines. The main

branch doesn’t entirely conform, however.

Let’s move on to the tricolored heron below.

The central axis of the bird’s anterior half does seem to align fairly well

with the vertical guide line, and the axis of the head and beak do seem

to average to a conformation nicely intersecting the upper horizontal

guide line. The eye almost falls on a power point. What I

like about this image—forgetting about the division lines for now—is

that the bird has a lot of space on the left to look at, and to move

into if it so chooses. That is, the bird’s world—as imagined by

the viewer of the image—contains enough space, in the direction that

the bird is facing, to possibly account for the bird’s attention being

focused where it is.

Fig. 8.1.4 :

Axes and spacing. Though the bird’s main axis seems fairly

well aligned with one of the division lines, the overall spacing around

the

bird seems more significant in this image. The bird has a

comfortable

margin above, below, and to its right, while the direction in which it’s

gazing is wide open, leaving more to the imagination.

Notice also in this image that the

water seems to asymptote

toward the lower horizontal line. The bird has a roughly equal

amount of space above and below it. Although it has plenty of

space to its left to contemplate, the bird isn’t right up against the

edge of the image on the other side.

Now on to the osprey below. The bird’s

horizontal axis lines up nicely with the lower guide line, and the

vertical axis of the wing lines up with the vertical guide line.

As with the previous image, there’s an equal amount of space above and

below the bird, and there’s at least some margin (albeit a small one)

behind the bird. I think this bird would look fine slightly

forward of its current position, but I think the framing shown as it is

could be more dramatic for large prints (20×30 inches or larger); for smaller

prints (8×10 or 11×14) I may indeed prefer to move

the bird foward a bit in the frame.

Fig. 8.1.5 :

Birds in flight need some place to fly to. Though this bird’s

horizontal

and vertical axes conform well with the rule of thirds, the eye does

not fall on a

power point. More important in this case is that no part of the

bird touches the

edge of the frame, while the bird has plenty of space in front of it,

leaving

the viewer room to imagine the bird’s trajectory and destination.

Moving on to the ruddy shelduck below, we see

that the bird’s vertical axis is almost perfectly aligned to the

vertical guide line on the left. In addition, the head falls

directly on a power point. The moonlight reflecting in the water

has a central axis that doesn’t quite coincide with the other vertical

guide line, but is at least close; in this case, moving the moon beam

to the right would eliminate the black margin, and would move the bird

into the center, both of which I’d prefer not to do. As in

previous images, the bird has comparable upper and lower margins.

I like having this bird centered vertically, since it’s off-center

horizontally. This also works out to keep the bird’s reflection

just barely contained in the frame. Any of these constraints

could have been violated to varying degrees, but what matters is the

sum of these individual effects—keeping in mind that not all of

these individual constraints are equally important.

Fig. 8.1.6 :

The bird isn’t the only important element of

the scene. Here the wide reflection of moonlight helps to

provide balance to the off-center bird. Enough vertical

spacing is provided to avoid clipping the bird’s reflection.

For the waterthrush below, we see

that the center of the bird’s body is well-centered around a power

point, and the water’s horizon is approaching the upper guide

line. There’s a significant color difference between the top

third of the image and the bottom two thirds. Note also that the “gully” or “pocket” of water centered around the

rightmost vertical

guide line in some ways seems to balance out the vertical protrusion on

the left that is the bird; this creates a subtle but powerful balance—or perhaps conflict—in the image.

Fig. 8.1.7 :

Yin and yang. The water gully below the horizon helps to balance

the positive projection of the bird above the horizon.

In the merganser image below, the

bird’s body aligns with the lower horizontal guide line, while the

vertical axis of the neck and head come close to aligning with the

vertical guide line. However, the water horizon doesn’t fall on a

guide line, and the bird’s eye is nowhere near a power point.

Also, the larger space is behind

the bird rather than in front of it, emphasizing where the bird has been rather than where it’s going to.

Fig. 8.1.8 :

Past versus present. Though it’s more common to leave the larger

amount of space in front of the bird, to allow for future trajectories,

here

the greater amount of space is behind the subject, emphasizing that the

bird

has been traveling for some distance, while also requiring

proportionally

more from the viewer’s imagination as to where the bird might be headed.

This is a good time to remind ourselves that the

rule of thirds (as well as the other pointers offered parenthetically

along the way) are just rules of

thumb—following them doesn’t guarantee perfection, and failing

to follow them doesn’t guarantee failure. In terms of the

much-celebrated rule of thirds,

the rule itself is actually a crude approximation to the golden ratio, which is believed by

many to underpin works by such great artists as Leonardo da Vinci and

Michelangelo. The golden ratio (also called the divine

ratio, or simply phi) places the guide lines

approximately 38% and 62% of the way across the canvas; the rule of

thirds revises these numbers to approximately 33% and 66%, which are a

bit easier to visualize when in the field since they divide the

viewfinder into simple thirds. In either case, the rules are just

“guidelines” (in a figurative and literal

sense) to help novices to get started—or for more experienced

photographers to fall back upon when the task of finding the right

composition proves especially difficult for a particular scene.

Now let’s consider some cases where the rule of

thirds has rather more limited applicability. The first notable

exception is when the entire subject doesn’t fit completely in the

frame. The golden eagle below falls into this category.

Fig. 8.1.9 :

Macro subjects make their own rules. When the bird fills

a rather considerable portion of the frame, the rule of thirds becomes

much less dominant in the overall dynamics of the scene. Here, the

bird’s vertical axis aligns well with the guide line, but the vertical

spacing is more pragmatic, with a very modest margin above and

enough of the bird’s lower half revealed to adequately define the

wing.

Although the axis implied by the

head and neck of this bird does roughly coincide with a vertical guide

line, the head lies above the horizontal guide and the eye does not

fall on a power point. In this case, positioning the eye on the

closest power point would, in my opinion, ruin the overall balance of

foreground (bird) to background, which I think is of paramount

importance for this particular image. Of similar importance in

this image is the left-right spacing of the bird: the bird has a lot of

space on the left to gaze into, and there’s a goodly margin separating

the bird from the rightmost edge of the frame. It’s also

important that none of the vertical lines in the background are

positioned close to either edge of the frame.

The prairie warbler below is also aligned well with

the vertical guide line, but again the eye misses the power

point. In this case, lowering the bird to allow the eye to fall

on the power point would bring the bird’s body down to the lower edge

of the frame, eliminating the branch that the bird is perched on.

For extremely close portrait shots like the golden eagle above, it’s

obviously not possible to show what the bird is perched on, but when

the bird is small enough to fit in the frame, showing its perch can

help the image to make more sense to the viewer.

Fig. 8.1.10 :

Space for perching and singing. A singing bird needs

some space for its sound waves to travel into. For perching birds,

showing at least some portion of the bird’s perch helps to allay any

(subconscious) fears the viewer may have about the bird’s stability.

In terms of the zoom level, note

that the bird is large enough to show

significant feather detail, but is small enough to avoid touching any

of the edges of the image. Also, since this bird is singing,

positioning the bird on the right allows its song to propagate (in the

mind of the viewer) toward the left for some distances before leaving

the frame. The latter consideration falls under what some would

call the dynamics of the

image—i.e., what the viewer imagines as happening after the instant

in time frozen by the image.

In the junco

image below, the bird’s vertical axis misses the guide line, but in

this case I specifically wanted the bird to be far over toward the

right margin, to give the viewer more landscape on the left to

contemplate (to help emphasize the smallness of the bird). There

is, however, some space separating the bird from the rightmost edge of

the frame, which I consider a nearly inviolable constraint for most

bird photographs.

Fig. 8.1.11 :

Exploring the extremes in spacing. Very little of this image

supports the rule of thirds. My main concerns in choosing this

composition

were that the subject not touch any edge of the frame, that the bird

have a

(relatively) wide landscape to gaze over, and that the color and space

distribution give the impression of a small bird in a rather larger

world.

The bird’s body does coincide

nicely with the lower horizontal guide

line, but I don’t consider that to be very important in this

case. The

slope of the land and the one-third / two-thirds balance between

foreground and background are obvious contributors to the overall

aesthetics in this image.

For the

magnolia warbler below, the rule of thirds contributes very little:

though the power point falls within the bird’s body, I don’t consider

that very important in this case (except for the fact that it keeps the

bird out of the very center of the image). The important features

here are that the bird has plenty of space in front of it, but has at

least ample margins on the other sides as well.

Fig. 8.1.12 :

Symmetry and complexity. Branches and diffuse background

patterns can contribute as much as the positioning of the main subject,

in terms of the overall balance and stability of the scene.

Note

that the positioning of the main branch (that the bird is perched on)

does often come into play in composing bird photos. Perfectly

horizontal branches often don’t look very good, while branches at odd

angles can contribute a deeper symmetry to the overall image geometry.

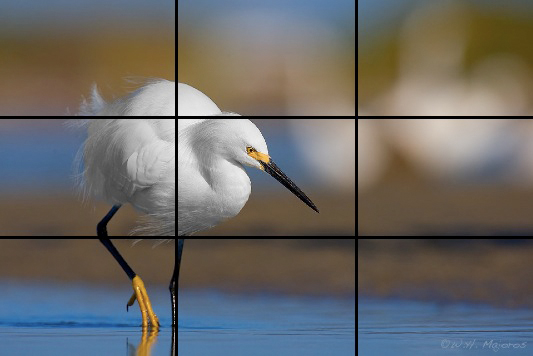

For the snowy

egret below, though the bird’s vertical axis does line up nicely with

the vertical guide line, I think what’s more important is the amount of

space around the bird, the entry point of the bird’s legs into the

water, and the overall color distribution. Although I could have

positioned the bird higher in the frame (thereby making marginally

greater use of the upper horizontal guide line), that would have

eliminated the thin band of blue sky at the top of the frame and

allowed greater dominance of the blue of the water at the bottom,

thereby changing the overall color distribution. In this case,

however, I probably didn’t have time to consider all of those issues

when shooting, since I was just trying to keep the subject in focus and

to capture the bird with its head at a nice angle and the legs in a

non-crossing configuration.

Fig. 8.1.13 :

A complex balancing act. Small changes in framing can

have significant implications for the overall impact of the scene,

including

the color distribution of the background, the overall horizontal and

vertical

balance of the salient features in the scene, and the psychological

ramifications

relating to the bird and its perceived behavioral dynamics.

As one final

example in the context of the rule of thirds, consider the mynah shown

below. The body axis intersects with the vertical guide line, but

the significance of this is somewhat doubtful. More important in

this photo is the space distribution. The spacing on the left and

right of the bird, in this case, follows a different sort of rule of “thirds”, with the space behind the bird

taking up roughly half as much

area as the space in front of the bird. Also, the bird has some

room above its head (which is always important), and the subtle

background gradient has enough space on the left for the black to turn

light again before reaching the edge of the frame.

Fig. 8.1.14 :

Applying the rule of thirds in a slightly different manner.

This mynah divides the background roughly into thirds, but in a

non-rectilinear fashion. Giving the bird enough headroom while

showing enough of its lower body, and retaining the lightening of

the background on the left were my main constraints for this shot.

When the

subject is extremely close, sometimes all you can do is try to capture

an abstract composition involving the bird’s head. In the pelican

photo below, it may be difficult for viewers to immediately tell what

kind of bird this is, and that may enhance their curiosity. I’ve

intentionally omitted the grid lines from this photo so you can

concentrate on observing the non-rectilinear proportions in the

image—such as the proportion of feathered body surface to skin, the

proportion of lighted surface to shadowed surface, and the relative

positions and sizes of the green background regions. These

proportions aren’t necessarily “perfect” in this particular instance,

but this should at least serve as an example of what you can do with

the distribution of textures and colors in an image via creative

framing (where “framing” in this case refers to

composition and bird

placement, not to the addition of an outer wooden frame).

Fig. 8.1.15 :

A study in proportions: feather to skin, sunlit to

shadowed, and foreground to background. These aren’t all

necessarily “perfectly” proportioned

here, but they give the

viewer something to contemplate—in addition to wondering

what kind of bird they’re looking at.

While all of

these considerations involving “divine proportions” and “golden ratios” may indeed have some merit in

both the analysis and construction of artistic images, in the field

there’s typically not enough time to think through these things

systematically. In the field I’m usually happy just to get an

in-focus, properly exposed image, which I might later be able to crop

(in Photoshop) into a pleasing composition. Even in those rare

occasions when the bird is so extremely cooperative that I can think

about composition, I never do so (explicitly) in terms of grid lines or

mathematical relations. Instead, I just search through the

possibilities for framing the subject and scenery until I see something

that strikes me as especially pleasing. In many cases I

intentionally blank my mind, letting the primitive instincts of my

visual cortex have free reign.

Finally, let’s consider the size of the bird in the

frame. If you have a zoom lens (or can change lenses or add

teleconverters) or can easily move closer to the bird or further away,

then you’ll typically be faced with having to decide how much “zooming”

(whether via the lens’ zoom or via your biological “foot zoom”) to apply before

taking the shot. In most cases, this is just another aesthetic

consideration. However, if you intend to make prints of your

images, it’s sometimes good to add a little extra space around the

outside of the frame, to account for any cropping that will be applied

by the printing process. This is primarily a concern when making

canvas wraps (see sections 14.1 and 14.2), in which case parts of the

image will

be wrapped around the sides of the underlying wooden frame. When

making canvas wraps, printers often stretch the canvas a bit further

than necessary, to ensure that no white canvas is showing around the

edges; this can sometimes result in the bird being closer to an edge

than you’d like, possibly even wrapping around onto the side

panel. Adding a wide margin when taking the shot can help to

avoid this problem. For traditional, framed and matted prints,

this is less of an issue, because the mat typically only covers a thin

margin around the outside of the image.

All of the foregoing composition techniques can be

used either in the field (with an especially cooperative bird) or later

during postprocessing, when trying to decide how to crop the image

around the subject. For fast-moving birds such as warblers, I

virtually never think of composition in the field; when dealing with

such small birds, there’s typically plenty of room around the bird in

the frame, affording much flexibility for creative cropping later in

postprocess. In these cases I’ll generally use the center focus

point and just keep the subject in the center of the frame.

During postprocessing I can decide whether to leave the bird in the

center or to crop off-center. Even with an 8 or 10 megapixel

camera you’ll often be able to crop the image fairly aggressively, at

least for images intended for viewing on a computer (e.g., via web

pages on the internet).

Although the position of the bird in the frame is

obviously of prime importance in bird photography, there are other

important aspects of image composition that need to be

considered. We’ll address several of these in the next two

sections of this

chapter. For now, just keep in mind that scene composition is an

artistic consideration, and as such is entirely up to you as the

artist. As an artist, it’s your right to choose whatever

composition feels best to you, and you shouldn’t feel pressured to

compose your images according to how someone else thinks you should

compose

them. Adhering too closely to the prescriptions of other

photographers is likely to lead to

images that are stylistically identical to the thousands of images

already published by the current crop of so-called “experts” and “professionals”. That’s fine, if that’s

what you want to do. In fact, imitating the “old masters” can be a great way to start out,

but in time you’ll likely feel the urge to exercise your own

creativity, and you shouldn’t feel pressured to supress that creativity

in order to satisfy someone else’s rules about how bird photos should

look. Think of your photographic activities as an opportunity to

explore your own artistic vision and instincts, rather than

as a prescriptive activity dictated by a handful of “experts”. Remember that there are no

rules in art. Following any set of rules can lead, in the long

term,

to stagnation. Above all, remember that art—even

photographic art—is something that you can do in pursuit of your own

personal happiness—whatever that means for you as an individual.

|