8.4 Getting Close

With relatively few exceptions,

the most common problem for bird photographers in the field is getting

close enough to capture a detailed image of the bird. Even

exposure problems due to limited lighting often reduce to the problem

of getting close enough for the effective use of flash. And

although there are certainly many instances in which the scenery itself

can carry the image and the bird therefore needn’t be especially large in the

frame, for hopelessly obsessed bird-lovers the feathered subject rarely

seems to be close enough to the camera. In this section we’ll

survey quite a wide variety of approaches to solving this most

fundamental of problems.

Fig. 8.4.1 :

Getting close usually isn’t this easy. In this case, the

enterprising tourist was able to get close to these free-ranging

wild birds because they had become accustomed to human

contact. City parks often have the tamest birds, for precisely

this reason.

The first task

in getting close to the bird is just finding

the bird. For birds that aren’t terribly common in your area of

residence, it’s often better to make a special trip to some place where

that bird is common, than to

try to capture the occasional image of the bird in suboptimal

habitat. As a case in point, I used to spend many hours trying to

get just one good warbler photo in my home town; now I instead make a

yearly 10-day trip to a warbler hot-spot far from home, where I can get

a hundredfold more photos of warblers in a single day than I could back

home in an entire season. It’s a simple matter of

efficiency. It’s more efficient for me to drive nine hours to

Ohio and intensively shoot for ten days, than to spend hundreds of

hours scouring the local parks in the North Carolina piedmont (where I

live) for a few mediocre warbler photos.

For birds that are

common in your home area, there are some definite strategies that you

can employ to (hopefully) improve your rate of contact with those

birds. The first strategy is to cast a wide net for information

about bird concentrations. Your local bird clubs or online forums

and e-mail listserves are good starting points. Other birders can

be a truly invaluable source of information about recent bird sightings

and also about observation sites that you may not know about

(especially sites that aren’t part of any official park).

Within a park or other natural area, a general

strategy for finding the species you’re looking for is to seek out the

wandering, mixed-species flocks that commonly rove about, especially

during non-breeding seasons. In North America, for example,

chickadees and titmice (genus: Parus)

often wander about together, and other birds such as warblers and the

like sometimes tag along behind them. So, even if you’re not

especially interested in chickadees or titmice, it may be productive to

hike around till you find a roving flock of these common birds, and to

then seek out the hangers-on that follow in their wake. Keep in

mind also that even photos of common birds can unexpectedly turn out to

be exceptional, if they capture the bird in a novel pose or with a

particularly striking background.

An especially effective strategy is one that can be

summed up in a single word: opportunism.

My personal philosophy is that by just wandering around photographing

the common birds that happen by, I should over the course of enough

time also encounter a goodly number of less-common birds without having

to specifically seek them out. In my experience, seeking out a

particular species of bird most often results in a depressingly low

rate of “return on investment”. When I go out in the field

I simply seek out any birds that I can find; in the process, I might

also encounter a number of unexpected varieties that in time can swell

the “species diversity” of my portfolio. The

advantage of being an opportunist is that you can avoid the frustration

of failing to find the bird you seek, while occasionally reaping the

rewards of the chance encounter with an unsought, but highly

appreciated, rare sighting.

There’s an old saying that “the harder you work, the luckier

you get.” This is, in fact, a

mathematical truth: as long as a desired event isn’t completely

precluded, the more chances you incur the greater the overall

probability that it will occur at least once over the aggregate trials

(or, more compactly: limn–>inf

1–(1–p)n=1, for 0<p<1). What this means for

the opportunistic bird photographer is that the more time you spend in

the field, the more high-quality photos you should get (on

average). As I look back on some of my own favorite photos, it

becomes increasingly clear to me that I owe those images to my large

investment of time in the field collecting lucky shots. There’s

no substitute for excessive amounts of time spent in the field.

While we’re on the topic of time, it’s worth

mentioning what should probably be obvious for any experienced bird

watcher—that early mornings and (to a lesser extent) early evenings can

be especially productive times of the day for bird photography.

We’ve already commented on the potential for sunset images (section

8.2). The hours spanning

sunrise and early morning are

potentially more important for many birds that have fasted all night

and need to procure calories to fuel their elevated metabolism.

When traveling to an exotic location for the purpose of bird

photography, it can be especially critical to put in morning and late

afternoon hours. In the hour before sunset many birds can be on

the move in search of roosting spots, or in search of those last few

calories needed to keep their metabolism going till morning. The

low angle of sunlight can also be beneficial at these times.

Although some people consider it “cheating”, a great way to increase your

contacts with birds is to bring them to you, by drawing them in with

bait. Setting up a birdfeeder close outside your window can be

extremely effective at bringing granivores (seed-eating birds) and

nectarivores (i.e., hummingbirds) within shooting range.

Fig. 8.4.2 :

Bribery is sometimes the best way to get what you want.

Carrying a small bag of birdseed with you in the field can sometimes

prove useful for attracting granivorous birds. I’ve used this

trick in

winter in areas where the birds could be heard but not seen.

Spreading a bit of seed on open surfaces can sometimes bring

them out where you can get photos of them.

Fruit-eating birds can also be

drawn in by setting out oranges or other types of fruits; some people

have also had luck drawing in orioles and other frugivores by putting

out some jelly, though this can be dangerous for hummingbirds because

they can get the jelly on their feathers and then get stuck or become

unable to fly. Suet also brings in many birds, including

woodpeckers and even some warblers.

Fig. 8.4.3 :

For some birds, fruit is a much better form of

bribery than birdseed. In addition to oranges, I’ve had

luck bringing in various frugivores with bananas,

cantaloupes, and even pineapples.

Away from home, bait can still be

used, though some care must be taken to ensure that legal and ethical

considerations are observed. In many parks and wildlife preserves

the feeding of any animal is prohibited, and these prohibitions are

often put in place to protect the animals. Feeding fish to

waterbirds at a fishing pier, for example, can be detrimental to the

birds since it’s likely to condition them to loiter at the pier, where

the constant presence of fish hooks can be a serious threat.

Fig. 8.4.4 :

Grains and fruits won’t work for carnivores. In environments

harboring many carnivorous waterbirds such as herons, egrets, and

pelicans,

a good strategy is to pick up a box of frozen sardines from the local

bait shop

and let them thaw in a cooler of tap water so you can set them out for

any

hesitant birds you may encounter in the field. I’ve only done

this once (in

Florida), but it worked like a charm, and I’ll probably do it again

when I

next have the opportunity.

Zoos and other places with captive birds—while again

technically “cheating” according to some people—are also

great places to get intimate shots of otherwise hard-to-find

birds. For those of us who have to work for a living (doing

something other than photography), the time and money constraints

typically make a trip to the zoo much more feasible than a trip to

Antarctica or Africa. There are some caveats involved with

shooting at zoos, however.

First, note that some zoos (such as the San Diego

Zoo) prohibit commercial use of photos taken of their animals.

Technically, this means you wouldn’t be able to sell your prints or

publish your images in a magazine (see Chapter 14 for tips on selling

bird photos). Some might also ban professional (or even

professional-looking) photographers, so be sure to call first and ask

about their policies).

A major difficulty in shooting zoo animals is that

there will typically be a cage or glass enclosure that you have to

shoot through. Glass can be a problem for flash photography, due

to the reflection from the glass; in some cases this can be mitigated

by shooting at an oblique angle to the glass, so the light reflects

away from the camera rather than toward it. I generally don’t

bother trying to shoot through glass at all, because it’s usually so

scratched and dirty that the resulting image would be terrible anyway.

Shooting through wire mesh, on the other hand, can

often work surprisingly well. The trick is to get as close to the

mesh as possible, and wait until the bird is far from the mesh.

Since you’ll be focusing on the bird, which is far from the mesh, the

mesh should be rendered out of focus if you use a large enough

aperture. In many cases you won’t be able to tell from the image

that the bird was in a cage. Obviously, you’ll want to ensure

that the background contains no visible man-made objects, if at all

possible.

Fig. 8.4.5 :

Photographing birds behind glass or wire mesh requires some care.

For glass, either don’t use flash, or use an oblique angle to avoid

flash glare.

For wire mesh, put your lens as close to the mesh as possible and use a

shallow

depth-of-field to render the mesh completely out of focus. The

above photo was

taken through wire mesh, which is so out-of-focus it’s invisible.

Even in the

wild, there are some locations in which the birds are much tamer than

elsewhere. At many locations in Florida, for example, the birds

are so tame that you can literally walk right up to the bird and take

its photo from a distance of mere yards or even feet. Elsewhere,

birds tend to be approachable in small city parks more than in outlying

suburban parks, because the birds living there are constantly exposed

to people and are less wary of them. Formal gardens can be great

places to find granivores, due to the availability and variety of seeds

year-round. Duck ponds where children feed the ducks are likewise

very productive.

For truly wild birds out in the wilderness, a good

strategy for increasing your sightings of the bird is to find its

nest. During the breeding season, finding an active bird’s nest

is like a give from heaven. When the chicks are in the nest the

adults can be expected to return regularly to deliver food, and these

comings and goings provide opportunities for getting the bird in

flight. Finding nests can be very difficult; one strategy for

finding them is to follow the birds in the field, and especially take

note of any bird that you repeatedly see flying by in the same

direction over the course of an hour or so.

Fig.

8.4.6 :

Finding a nest can be a godsend. In spring, take particular note

of any bird that seems to be flying repeatedly to the same location, or

that

flies past you going in the same direction. It could be a parent

making

frequent deliveries to a nest full of chicks.

If you do find a bird’s nest, be

extremely careful not to endanger the birds by getting too close.

Some birds, such as bald eagles, can be extremely sensitive to the

presence of humans close to the nest, and may abandon the nest (and the

chicks) if they feel harassed. Also, walking right up to

the tree in which a bird is nesting can lead raccoons to the nest by

laying a trail of your scent up to the tree; many naturalists who’ve

tried to help out a bird family by removing parasitic cowbirds or

cuckoos from another species’ nest have returned the following

day to find that raccoons came during the night and ate the remaining

chicks. Always keep the safety and comfort of the bird at the

very top of your priority list whenever you’re in the field, and most

especially so at nests.

In addition to

nests, another good find is a favorite perch. Some exposed snags

make such good perches that many different birds can be seen using them

over time. Some birds have a daily routine that places them on a

particular perch at nearly the same time every day. If you find a

situation like this, you can set up shop near the perch and wait for

the bird to come; landing shots of a bird approaching a perch can be

very nice.

Fig. 8.4.7 :

If you know the bird’s daily schedule, you can try to get to

where it’s going before it gets there. For the photo above, I

knew that

the birds would be coming in for the 3:30pm daily feeding at the wild

bird center in the Florida keys. They show up like clockwork

every day.

For waterbirds the way to get close is to approach

low by crawling or

slithering on your belly up to the edge of the water. By staying

low you can either avoid being seen by the bird, or avoid scaring it

away if it does see you; a low angle is also a good one for artistic

reasons (see section 8.2). There are some

things you can do to

make such a low approach easier. First, using a frying pan as

mentioned earlier can make it much easier to slide your large camera

rig along. Wearing gloves and knee pads can reduce some of the

discomfort when crawling on your hands and knees, though obviously your

gloves could get very dirty and then be useful later when operating the

camera. While sliding over hard mud or sand, a tarp can be used

to keep your clothes from getting too soiled, though doing so quietly

can be very difficult.

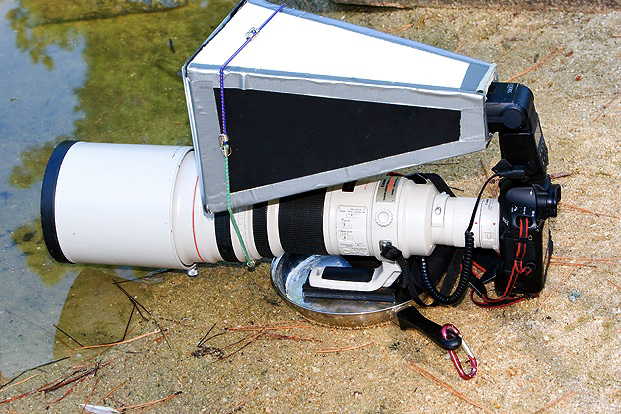

Fig. 8.4.8 : A

frying pan can be useful not only when shooting from a low

angle, but also when approaching on your hands and knees, since you can

slide the pan and its contents along on the ground ahead of you.

A popular way

to get close to

birds in the wild is to stake out a photo blind. I’ve rarely had

any luck with this, because there aren’t many blinds in the places

where I go, and the’re rarely located exactly where the birds

are. An alternative is to use some sort of portable blind.

Small, lightweight camouflage tents are available from hunting supply

stores; these can be can be carried fairly easily in the field and then

set up wherever needed, though they tend to be cramped and in the

summer they can get quite hot inside. An even more flexible

alternative is to use what might be called a wearable blind—that is, to apply

heavy camouflage to yourself and your equipment, so that all you need

to do when you find a good location for shooting is to just remain

still and effortlessly blend in. The photo below (courtesy of Fred Hurteau)

illustrates this strategy very nicely.

Fig. 8.4.9 :

Camouflaging yourself and your photo rig can sometimes be as effective

as

using a stationary photo blind, while permitting far greater

mobility.

Photo ©Fred

Hurteau, used with permission.

In some places

you can use your car as a blind. Sitting in the car with your

lens resting on the window frame, you can sometimes gain the trust of

birds easier than if you were standing outside your car. The hawk

photo shown below was captured this way. The bird was actually

hunting along a busy road when I happened to be driving by. Over

the course of twenty minutes I was able to progressively reposition my

car until I was within about 20 feet of the bird. Note that the

background of the image has been replaced in Photoshop; the original

background featured a hotdog stand (!).

Fig. 8.4.10 : A

hawk I photographed from my car. I found this bird

hunting next to the road. I pulled over and slowly positioned my

car within shooting range. Because the background included a

hotdog stand, I replaced it in Photoshop.

You can buy special window-mount supports for your lens to use in the

car, but I’ve never tried these. In the few cases where I’ve used

my car as a blind, the use of special window-mounting hardware either

would have taken too long to set up, or simply wasn’t needed.

Just be careful not to drop your lens out the window (or to

accidentally press the electronic window control).

When approaching any bird, it’s obviously important

to try to avoid getting so close that you scare off the bird. One

way to do this is to watch the bird very carefully and study its

behavior for any signs that the bird is becoming alarmed. If the

bird continues foraging without taking any notice of you, it’s usually

safe to continue approaching (slowly). If the bird stops what it’s

doing and looks at you (even if with only one eye), it’s best to stop

your approach, remain very still, and wait to see what the bird does

next; it may even help to turn around and face away from the bird, to

allay any fears the bird may have that you’re a predator hunting for

food. Depending on how desperate you are to get any photo of the

bird at all, you may want to hold off flashing the bird until it again

appears relaxed, since flash might scare off an already alarmed

bird. And as already mentioned, always respect the bird.

There are a number of factors that can influence how

approachable a bird is. As previously mentioned, birds living in

city parks tend to be more approachable than the same species living in

secluded areas. Juveniles tend to be more approachable than

adults (a good thing to keep in mind in summer). Predatory birds

feeding on large prey items are sometimes more approachable than they

otherwise would be (since flying off would probably mean losing their

meal). The species of the bird matters

too: belted kingfishers (Megaceryle

alcyon) are usually very difficult to get close to, while

saw-whet owls (Aegolius acadicus)

are reputed to be so approachable that it’s possible to walk right up

to the bird and photograph it with a macro lens. Finally, daily

contact with the same individual will sometimes allow you to earn the

bird’s trust (to some degree). In the case of

the osprey (Pandion haliaeetus)

photo below, I was standing almost directly beneath the

bird; most raptors would fly off before you even got close to the

tree. In this case, the bird was a juvenile with a carcass, and

had become accustomed to my presence over the course of several weeks.

Fig. 8.4.11 :

An osprey I photographed while standing almost directly beneath it.

Several factors allowed me to get so close. First, the bird is a

juvenile. Second, the

bird was familiar with me and my camera rig, since it saw me almost

every day at

its nest while it was growing up. Finally, the bird was feeding

on a carcass, which

would have been slightly inconvenient to fly away with.

One strategy

that will occasionally pay off is to observe which way a foraging bird

or flock is moving, and to position yourself so as to be in the bird’s

path. In other words, let the

bird come to you. I’ve found that birds will often come

much closer to me than they’ll let me approach them. This

strategy also has the advantage that it allows you to get some test

shots (to fine-tune your exposure and flash ratio) while the bird is

approaching you; taking test shots while you’re approaching the bird

can often be much more difficult (e.g., when you’re crawling on your

belly or have your tripod slung over your shoulder).

Fig. 8.4.12 :

Instead of approaching the bird, it’s sometimes better to wait for

the bird to approach you. When I saw that this sandpiper was

foraging along

a narrow strip of land bordering a pond, I positioned myself further

along the

shore and waited. Once it had approached to within shooting

distance, I

continued to wait until the bird presented a good pose. When the

bird began

stalking a fly perched on a wooden piling nearby, I knew the right

moment was near.

If you do

decide to approach the bird (rather than waiting for it to approach

you), there are several important things to keep in mind. First,

many birds are suspicious of long, gun-shaped objects, so be careful

about swinging your huge lens or tripod around when you’re within “firing distance” of the bird. Move slowly

and try to avoid

moving directly toward the subject. If the bird is looking in

your direction, then try to avoid staring at it while you approach

obliquely. If there’s a wide-boled tree between you and the bird,

it sometimes helps to first move yourself behind the tree so that the

bird can’t see you; then walk straight toward the tree (remaining out

of the bird’s view), and upon reaching the tree step out very slowly

from behind it. This sometimes allows you to approach the bird

far more rapidly than if you had to slowly walk toward it in open view,

and the savings in time may buy you a few additional shots before the

bird eventually finishes its business (whatever that happens to be) and

flies off.

In terms of actually finding birds to photograph, there

are two main strategies: the sit-and-wait

approach, and deliberate searching

(which usually means wandering around at random). Which strategy

is better depends on the circumstances. I find that actively

searching (i.e., wandering aimlessly) often works better for me, in the

types of locations where I go to do my birding. I typically only

try the sit-and-wait approach when I’m at a concentrated food source

(such as a berry bush) that I think birds are likely to visit

regularly, and even then I usually give up and revert to wandering if

they don’t show up within a certain amount of time.

Around water, searching for birds or following them

once you’ve found them can get tricky. Some people like to do

their birding in these types of environments by boat (i.e. in a canoe

or kayak), though personally I’m rather hesitant to try this, due to

the possibility of water damage to my equipment. The potential

for getting close to otherwise inaccessible birds, however, makes this

a very tempting option. Serious waterbirders have been known to

go to great lengths to camouflage their crafts, resulting in floating

photo blinds that can get their occupant within literally inches of

their quarry. The photo below (courtesy of Fred Hurteau)

illustrates just how cryptic these vessels can be made to be.

Fig. 8.4.13 :

Believe it or not, there’s a boat in this picture! The heavily

camouflaged

boat is “parked” at the edge of

a lake, and its occupant, also heavily camouflaged,

is wielding a camera with a small lens. A rig like this can

sometimes get you so

close to your quarry that you don’t need a big lens to get a

frame-filling shot.

Photo ©Fred Hurteau,

used with permission.

For shallow water (such as in a marsh, or along a

lakeshore), the use of a boat may be overkill. For these types of

environments, wading boots can be very useful when trying to find or

follow a bird. I’ve personally used thigh waders fairly

extensively while following prothonotary warblers (Protonotaria citrea) around in a

marshy area at the edge of a lake, and also for getting better angles

when shooting tame ducks at a duck pond. Though I’ve not yet

tried using chest waders, I’d imagine that they could provide even more

flexibility in environments with moderately deep water.

Fig. 8.4.14 :

Prothonotary warbler photographed at the edge of a shallow pool.

To get this angle I had to wade in knee-deep water; thigh waders kept

me dry. I

followed this individual bird around, off and on, for about eight

hours one day as it

foraged in a marshy area next to a lake. Without the wading

boots I would have

been much less comfortable. Note that after eight hours the

bird was still foraging,

but I had to go home because I was dead-tired from

hand-holding my huge lens

all day. It’s the only time

I’ve had my

rear-end handed to me by a three-inch bird.

It goes without

saying that the use of

higher-magnification optics effectively “gets you closer” to the bird—or rather, moderates

the necessity of getting as close (physically) as you’d otherwise need

to do. Higher magnification (i.e., focal length) can help only so

much, however, and can in some cases be a hindrance. When

shooting over a large distance at high magnification, air turbulence

and even impurities (including even swarms of insects) in the air can

noticeably degrade image quality; in this way, using higher

magnification isn’t exactly the same as being closer to the bird.

On the other hand, higher magnifications may allow you to avoid

disturbing the bird, by keeping a more respectful distance.

Keeping a 1.4× and/or 2× teleconverter in your pocket will

at least give you the option of using higher magnification when you

need it.

Keep in mind that the use of teleconverters does

come with some compromises. First, putting on and taking off the

teleconverter in the field can be very inconvenient, and increases the

chance of getting dust particles into the mirror box that can then

migrate onto the imaging sensor, resulting in visible dust spots in

images. Teleconverters decrease the aperture, and for many

camera/lens combinations this will disable autofocus capability, or

force you to perform autofocus with the center AF point only.

Attaching the teleconverter involves introducing a number of additional

glass elements into the imaging light path, which can reduce sharpness

and possibly affect image quality in other ways (such as via aberrations—see section 3.3).

Finally, by using a higher magnification you exacerbate the

effect of optical leveraging

(section 3.5), which effectively magnifies the

blurring effect of

camera shake.

Fig.

8.4.15 :

Pelican perched on the author’s camera.

It’s amazing how

close birds will get when they’ve

been acclimated to human presence. This was obviously

one of those cases where a high-power lens was rather

less useful for magnifying the bird—though it

turned out

to be useful for supporting the bird!

|