|

| Whereas Part I of

this book provided guidance on buying the equipment you need

for high-quality bird photography, Part

II gives instruction on the

effective operation of that equipment. We begin with the

technical

aspects of operating the camera and the external flash so as to capture

sharp images that are properly exposed

(i.e., well-lit). After

this

we expand the discussion to a broader range of practical issues that

are relevant when shooting in the field, such as choosing the right

angle and composition, making

the best use of light and background

colors, and capturing the bird in the ideal pose. We’ll conclude Part

II with some pointers on turning your yard into an aesthetic

bird-photography studio. |

Chapter

6

Operating

the Camera

In

Chapter 2 we reviewed the basic technology underlying today’s

DSLR’s.

As we now consider the effective operation of the camera in the field,

we’ll rely on a number of concepts introduced in that earlier

chapter.

Though we’ll briefly review essential concepts where necessary, it may

be useful to skim through Chapter 2 at various points

in order to most effectively digest the material presented here.

6.1

F-stops, Shutter Speeds, and ISO

The very first task in learning to

use your DSLR is to master the skills involved in obtaining a good exposure—that is, in getting a

photo in which the bird is lit well

enough that you can discern sufficient detail in the bird’s plumage and

other features. Of course, the “correct” exposure of a bird

depends to a very large degree on what you’re trying to achieve,

aesthetically, with the image that you’re crafting: you may want the

scene to have a dreary, subdued mood, or you might be trying to achieve

a “high key” effect in which the photo is

excessively bright, for

artistic reasons. For now, however, we’ll concentrate on the more

basic task of maximizing the amount of detail visible in the bird, and

leave the more artistic considerations for later.

As explained in Chapter 2, there are three

settings that you can manipulate in the camera in order to affect the

exposure (brightness) of an image: the aperture, the shutter speed,

and the ISO setting.

The aperture is the easiest to understand:

a wider hole, or aperture, will let in more light per unit time,

resulting in brighter images. The aperture that we’re talking

about here is the diaphram

(or iris) located within the

lens.

This diaphram can be opened or closed to varying sizes, resulting in

changes to the amount of light that passes through the lens.

Recall from section 3.1 that a larger aperture

(wider hole) corresponds

to a smaller f-number; thus, f/8 lets in more light than f/11.

Fig. 6.1.1 :

F-numbers and aperture are inversely related. As the f-number is

varied from

2.8 (at left) to 32 (at right), the aperture decreases in size.

This is counter-intuitive, but it’s

absolutely essential to remember this fact when shooting in the

field. Otherwise, you’ll

find yourself adjusting exposure parameters in the wrong direction,

resulting in useless shots.

Light passing through the lens (and diaphram) only

reaches the imaging sensor when the shutter is open, and the amount of

time that the shutter is open is dependent on the shutter speed.

Obviously, if the shutter opens and closes very quickly, less light

will reach the sensor than if the shutter opens and closes

slowly. Thus, a faster shutter speed results in a darker exposure.

Fig. 6.1.2 :

The three exposure parameters in DLSRs (left-to-right): ISO, shutter

speed, and aperture.

The aperture limits light via space constraints, the shutter speed

limits light via time constraints,

and the ISO setting artificially amplifies the signal (and noise) from

the imaging sensor after

exposure has already taken place.

Finally, we have the ISO setting. Recall from

section 2.5 that the ISO setting controls the

amount by which the

analog output of the sensor (the signal,

as well as any attendant noise) is amplified before being converted to

digital pixel encodings. Because higher signal

values result in brighter pixels in the resulting image, turning up the

ISO (i.e., increasing the amount of amplification) will cause the

resulting image to look brighter (though possibly also noisier).

We thus have the following simple rules:

If

you want a brighter image...

|

If

you want a darker image...

|

| decrease

the shutter speed |

increase

the shutter speed |

enlarge

the aperture

(decrease the f-number) |

constrict

the aperture

(increase f-number) |

increase

the ISO

|

decrease

the ISO

|

Table. 6.1.1 :

The Fundamental Rules of Exposure.

Note that if you’re shooting in

Manual Exposure mode, you can apply these rules

directly. However, if you’re shooting in

one of the Automatic Exposure modes

(section 6.3) you’ll instead need

to adjust a pseudo-parameter called “exposure

compensation”, because in

the Automatic Exposure modes, the camera tries to

maintain a constant brightness by trading off one parameter for

another. All of

this is explained in section 6.3.

For example, if you take a photo

(in manual exposure mode—section 6.3)

and then, upon

reviewing the image on

the camera’s LCD, decide that it’s too dark, you can make sure the next

photo (of the same scene) turns out brighter than this one by either

increasing the ISO,

enlarging the aperture (i.e., using a smaller f-number), or decreasing

the shutter speed (or some equivalent combination). If after

making the adjustment(s) to these settings, you find that the next

photo is still too dark, then you can simply adjust one or more of the

settings further and try again, and repeat this process until you get

an image that has just the right amount of exposure. This

trial-and-error process may seem slow and wasteful, but in time (with

experience in the field) you’ll get better at adjusting these three

settings rapidly and in the proper amounts, so as to hone in on the

right values with fewer trials.

Fig. 6.1.3 :

Finding the right exposure settings via highlight alerts. This

rock was

the whitest object I could find at the beginning of a shooting session

at a bald eagle

hotspot. Adult bald eagles have white heads, so I chose my

exposure parameters

so as to avoid overexposing white objects. The red indicator

pixels show that

I was clipping some highlights. After seeing this on my camera’s

LCD, I turned

down the exposure until the highlight alerts indicated no clipping of

highlights.

Now we need to consider some of the complications

involved in adjusting these three parameters (aperture, shutter speed,

ISO). The good news is that there isn’t a single, unique

combination of the three parameters that results in the “correct”

exposure. Once you’ve found a setting that gives you an exposure

that you like, it’s possible to change two or more of the parameters

(in the proper way) and still get the same overall level of

brightness. For example, if you were to turn the f-number down

one “click” on your camera’s aperture dial

(say, from f/8 to f/7.1),

and then turn the shutter speed up

one click on your camera’s

shutter-speed dial (say, from 1/320 to 1/400), you should find that the

resulting exposure hasn’t

changed. That’s because the larger aperture (smaller f-number)

has been counterbalanced by the increase in shutter speed. This

is called reciprocity. Reciprocity works by trading off “stops” of light between

parameters. A stop of

light corresponds to a doubling/halving of the shutter speed (or ISO),

or multiplying/dividing the f-number

by 1.4 (the square root of 2). In practice, you can usually

forget about the exact definitions (multiples of 2 versus 1.4) and just

think in terms of clicks on the parameter dials.

So the good

news is that you’re not looking for a

needle in a haystack: a number of different combinations of ISO /

aperture / shutter speed will typically give you a good exposure, and

you just need to find one of

those combinations. The bad news is

that there are secondary effects of adjusting these parameters—that

is, other effects besides just changing the exposure. As we

explained in section 3.7, for example,

enlarging the aperture not only

increases the amount of light collected, it also results in a shallower

depth of field

(DOF). Sometimes you’ll want to do both (increase

brightness and decrease DOF), and in those cases you can achieve that

by adjusting the aperture. If, however, you don’t want to

change the DOF, then you’ll have to resort to changing one of the other

two parameters (ISO or shutter speed) in order to adjust the exposure.

Fig. 6.1.4 :

Snowy egret in a shallow depth-of-field (DOF). Because I wanted

to isolate my

subject, I set my aperture very wide, and then calibrated my

exposure by adjusting the

shutter speed and ISO (but not the aperture). When one of the

exposure parameters is

constrained for artistic reasons, adjusting the brightness has to be

done using the other

parameters. (1/1250 sec, f/6.3, ISO 125, 600mm, manual

mode, TTL flash at +1

FEC).

Similarly, changing the ISO or shutter speed can

have other effects on the resulting image. Increasing the ISO can

increase the noise level (as explained in section 2.5),

while

decreasing the shutter speed can decrease the sharpness of the image,

due to motion blur. Thus, the challenge is in finding the

combination of these three parameters which gives you an acceptable

exposure, without producing too much noise (via high ISO) or motion

blur (via low shutter speeds); in addition, if you’re trying to achieve

a specific effect via DOF (such as isolating the bird via a shallow

DOF), then you’ll want to find a combination of parameters that doesn’t

violate your desired DOF.

To make matters worse, there are limits on how high

or low you can set each of these parameters, and it’s not uncommon to

run into some of those limits in the field. Native ISO values are

typically limited to a range of 100 to 1600; “expanded” ISO

ranges typically are only “simulated” and should generally be avoided

if possible. Apertures are likewise limited at both the high and

low ends of the range, though it’s the upper limit that is most often

encountered in the field, since the objective lens diameter limits how

wide the aperture can be made. Though shutter speeds are also

limited at the high end (typically 1/8000 sec for pro bodies) as well

as at the low end (typically 30 seconds), in practice you’ll want to

avoid going below 1/125 or 1/160 sec (plus or minus, depending on

whether you’re using a tripod and/or image stabilization) in order to

avoid image blur (or 1/640 to 1/1600 for birds in flight, or even just

small birds frantically foraging).

Fig. 6.1.5 : In

intense shooting situations, you need to be able to change exposure

parameters quickly, and correctly, without exceeding key limits.

For this shot,

I got a reasonable exposure (clipping some of the highlights on the

back of the

bird in order to make details visible on the underside), but I allowed

the shutter

speed to go too low, resulting in motion blur. Fortunately, the

image ended up

having a dreamy, artistic effect that I like. Notice the

eye-shine from my flash,

which normally I'd fix in Photoshop. (1/50 sec, f/10, ISO 125,

600mm, Av with

-1 EC, TTL flash)

Fortunately, as we’ll see in section 6.3, there are

several exposure modes that

you can use to make it easier to manage

the three parameters affecting exposure. What you’ll typically

find in the field, however, is that you only need to search for your

optimal parameters at the beginning of the day’s session, and then to

gradually adjust individual parameters a little bit throughout the

session, as the lighting changes (i.e., as cloud cover comes and

goes). Furthermore, if you do most of your birding at the same

place several days in a row, you’ll often find that establishing your

initial settings at the start of each session is easier, since they’ll

likely be the same settings you used at the start of yesterday’s

session, and may be just a few “clicks” (on the parameter dials on your

camera) away from whatever setting the camera was left in when you

turned it off at the end of the last session.

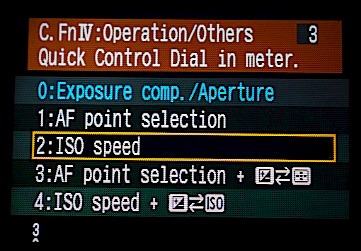

Fig. 6.1.6 :

Changing the behavior of the “thumb dial” on

the Canon 1D Mark III. For some situations I like to

set it to control ISO. Another menu option allows me

to swap it between shutter speed and aperture.

One trick that

can help you to become faster at adjusting exposure parameters is to

reassign the camera’s dials and buttons (if your camera allows you to

do that) to particular exposure parameters, depending on your shooting

style and exposure mode. For example, if you find that in a

particular birding situation you tend to adjust the ISO and aperture

more often than you adjust the shutter speed, then you could assign

those two parameters (ISO and aperture) to the two dials or joysticks

on your camera that are most easily within your reach. My current

camera has two dials, and I typically assign shutter speed and aperture

to these; adjusting the ISO can then be done by first pressing a button

and then turning the dial that normally changes the shutter

speed. However, if I’m birding in a dim environment, such that

I’m limited primarily by my shutter speed, then I may set the shutter

speed to its lowest practical value (say, 1/160 sec) and then assign

the two dials to ISO and aperture. Unfortunately, not all cameras

allow you to reassign their controls in this way.

Note that when trying to freeze birds, a faster

shutter speed isn’t always the ideal solution. As previously

mentioned, birds in flight often need a shutter speed of 1/640 to 1/800

sec for slow-flapping birds or 1/1600 to 1/2000 sec or faster for

fast-flapping birds. Even the fast head movements of foraging

birds (especially warblers and small shorebirds) can require speeds of

1/1600 or more to freeze. When these speeds aren’t feasible, due

to exposure constraints, flash can sometimes be used to freeze the bird

by keeping ambient light low and using a short flash duration (see section

7.7). In the case of foraging

birds (i.e., those not in flight),

if you’re already using flash for fill light then it’s often preferable

to keep your shutter speed below the sync

speed (to maximize effective flash output and minimize recycle

time), and just try to get the bird while it’s not moving. I’ve

found that for shooting frantically feeding warblers, 1/1600 sec

sometimes isn’t fast enough to eliminate motion blur, so I instead

shoot at 1/300 sec (the sync speed of my camera) and take lots and lots

of photos in hopes of getting the occasional lucky shot when the bird

is perfectly still. This is sometimes the only way to fully

dispel the shadows in the scene. Flash is dicussed in greater

detail in Chapter 7.

|

|

|