10.6 Selection

Of all the processing features

available in Photoshop, the most powerful—for processing bird

photos—is, by far, its array of tools for selecting parts of an image

and processing those elements differently from the rest of the

scene. The flexible

and efficient selection methods in Photoshop are nothing less than a

godsend to bird photographers. The reason is simple: people who

spend time looking at (or even buying) bird photos do so because they

are, in the majority of cases, inordinately fond of birds. They

therefore place greater importance on the aesthetic qualities of

the bird in any given image than would a casual viewer, and are

by-and-large impressed the most by

photos in which the bird stands out prominently from its

background. Notwithstanding the proverbial

exception-to-every-rule, for avian art the bird, as the principal

subject, needs to occupy a central place in the awareness of the viewer

(even if not centrally located in the image frame). Differential

processing of the bird versus its background—even if only subtle—is

thus a key capability in any workflow involving the producion of avian

art.

We’ve already seen, in section 10.3,

that Photoshop

allows for efficient differential processing via the separation of

image elements into different layers

(though we’ll see later that

differential processing is possible even without the explicit use of

layers). In order to separate image

elements into different layers, however, you first need to be able to select them.

That is precisely what we want to address in this

section: how to select the bird (or any other part of the image) via

the cursor-controlled tools available in Photoshop. In

particularly, we’ll want to explore how to select the bird efficiently (without having to

spend excessive amounts of time fiddling with the computer’s mouse) and

accurately (so

that the selection

boundary follows the bird’s outline with sufficient exactitude).

We will proceed via concrete examples. The

first is illustrated below. Here, the bird has been hastily

selected via the Lasso tool

in Photoshop. The black-and-white

dashed line roughly following the bird’s contour indicates the current

selection. As you can see, this selection isn’t perfect, since

some parts of the bird lie outside the selection, and a few pixels from

the background fall within the selection. For some applications,

such a sloppy selection may be good enough for the task at hand, but

for many it won’t. We’ll see shortly how to get more accurate

selections using other tools.

Fig. 10.6.1:

Selecting the bird using the Lasso tool. This selection is very

sloppy: some of the bird lies outside the selection, and a few pixels

from

the background lie within the selection. The Lasso tool is very

difficult

to use (especially with a trackball), so I recommend avoiding it.

The way this selection was created

is as follows. First, I clicked on the Lasso tool’s icon in the

toolbar. Then I clicked on an arbitrary starting point on the

bird’s outer boundary, and then without releasing the mouse button I

dragged the mouse cursor (using my computer’s trackball, which is

similar to a mouse) so as to trace the outline of the bird. When

I had traced a complete circuit around the bird’s outline, I released

the mouse button. Selecting a bird this way can be quite tedious,

and is rarely as accurate as you’d like.

Fortunately, there are

better options in Photoshop for selecting complex shapes—options that

can be far more accurate without requiring much more effort (once

you’ve had some practice). Some of

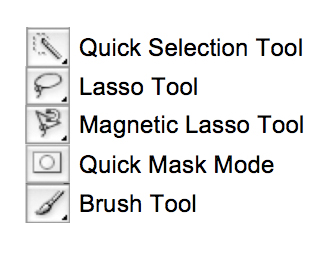

Photoshop’s selection tools are depicted in iconic form in the figure

below.

Fig. 10.6.2:

Some of the selection tools in Photoshop’s

toolbar. Clicking on a tool’s icon in the toolbar turns

your mouse cursor into that tool. For the icons with a

small triangle in the lower right corner, holding down

the mouse button while clicking the icon will bring up

a second palette with additional tools in the same family.

Most tools have keyboard shortcuts, for faster access.

We’ve already encountered the Lasso tool; the Magnetic Lasso tool is

similar, except that the computer tries to help you by fixing what it

perceives as your “mistakes” (i.e., errors in the trajectory

of your

mouse cursor), while you’re in the process of making

them. For example, if while tracing the bird’s contour with the

mouse cursor you accidentally slip and veer outside the bird’s contour

a bit, the Magnetic Lasso will (in the ideal case) notice your mistake

and automatically correct it for you by re-routing the selection

boundary to correspond more closely with the outer edge of the

bird. This can work well if the bird’s contour is strongly

defined in the image (i.e., via an abrupt contrast differential at the

pixel level), but in many cases the tool will get confused and re-route

your selection in a way that makes it worse than if it hadn’t

intervened. This tool can be very frustrating to use.

Fortunately, there’s a better way: the Quick Selection tool. This is

the method I use for 95% of my work. It has some predictive

intelligence built into it, much like the Magnetic Lasso, but is far

easier to control, as we’ll see. The main technological

difference is that with the Quick Selection tool you’re selecting regions, not boundaries, and the tool can

quickly infer what you’re trying to select in the image by studying the

pixels you’ve already selected (as well as those you’ve explicitly de-selected). Because it has

more data to work with (i.e., more pixels to learn from), it often

makes much more intelligent decisions than the Magnetic Lasso.

Let’s consider how this remarkable tool can be used in practice to

rapidly and accurately select a bird from an image.

After clicking on the Quick

Selection tool’s icon in the tools palette, you’ll then need to select

a brush size, as

depicted in the figure below. The “Diameter”

slider controls your brush size (we’ll consider “Hardness” in just a

moment—for now you should leave it at 100%—but the other parameters you can

simply ignore). A good rule of

thumb is to start out with a brush size that is larger than the bird’s

eyeball, but smaller than its head.

Fig. 10.6.3:

Setting the brush size in the Quick Selection tool.

The brush size is important, because you’ll be using the brush

to sweep out regions that you want to select, and if the brush

is too big it won't be able to fit in all parts of the bird, while

if it’s too small it’ll take to longer to sweep out the whole bird.

A good rule of thumb is to choose a size larger than the bird’s

eyeball but smaller than its head. You’ll see the size of your

cursor change as your move the Diameter slider.

Once you’ve chosen a brush size, you’re ready to select the

bird. To do so, simply click the computer’s mouse anywhere inside

the bird,

and while still holding down the mouse button, drag the mouse cursor

around inside the subject. Photoshop will try to intelligently expand your selection to the

nearest natural boundaries in the image. In many situations, this

works very well—often extremely

well—in which case you’ll see the

selection contour almost magically expand to the precise outline of the

bird. In other cases it’s not quite so impressive, but at least

in the case of birds I’ve almost always found this tool to be the most

efficient means of selecting the subject. It does require some

practice, however, and there are a few important tips you need to be

aware of.

First, you can use the tool to both add to the selection and to subtract from it. Note that

in the tool’s settings pane

there are several icons, two of which look like this:

Make sure you click on the left icon (with the “+” sign) before you begin using the

tool. That will allow you to add to your original selection by

making additional clicks and sweeps with the mouse. If you

accidentally draw outside the bird, or if Photoshop is too aggressive

in automatically expanding your selection region, you can de-select regions by holding down

the option/alt key while

using the tool.

Holding down the option/alt

key temporarily puts the tool into its “subtract” mode; you’d get the same behavior

by exlicitly clicking on the second icon shown above (the one with the

minus sign), but I find that it’s much faster to just keep my finger on

the option/alt key when I’m using this tool, and then I can quickly

press or release that key as needed to switch between the add and

subtract modes. Once you become skilled at using this tool in

both its add and subtract modes, you’ll be able to rapidly select just

about any bird through a series of sweeps with the Quick Selection tool.

Note that you can use the tool in subtract mode even

on

regions that haven’t been selected—doing so explicitly tells Photoshop

that you don’t want it to

select that region later when you go into the

add mode and sweep the cursor nearby. This can be useful when you

notice that some part of the bird blends into the background.

If you just used the add mode you might find that when you near that

part of the bird the selection suddenly expands to include the entire

background region, which might then take a bit of work to explicitly

de-select. If you were instead to sweep out the “off-limits” area in the region where the bird

blends with its background, effectively tracing out a boundary that the

selection should not cross, then when you later switch to the add mode

you should find that Photoshop is more reluctant to expand the

selection into that off-limits region.

When using this tool you’ll also need to make

changes to your brush size periodically. As suggsted above, a

good rule of thumb is to start with a brush size that’s small enough to

fit within the bird’s head. If you start with a brush that’s too

small you’ll find that Photoshop doesn’t expand to the bird’s contour

as well, and may instead just expand to the nearest feather or group of

feathers, requiring more work on your part. The behavior of the

expansion algorithm used by

Photoshop is affected by the brush size, with a larger brush indicating

to Photoshop that the contour it’s looking for is on a correspondingly

larger scale. Once you’ve got the outline of the bird roughly

selected, it’s time to switch to a finer-scale brush and to zoom in a

bit (so that only part of the bird will probably fit on your

screen).

Now you can refine the selection boundary to more closely match the

contour of the bird. When doing this I make frequent use of the option/alt key to

rapidly switch between the add and subtract modes of

the tool, to nudge the selection boundary back and forth until it

precisely follows the bird’s silhouette. When working at the

finest scales

it’s sometimes useful to resort to single clicks of the mouse button,

rather than sweeping with a drag-and-drop type of motion, or at least

to use smaller sweeps rather than continuously “painting” as before. Rest

assured that you’ll get better at it as you gain more experience using

this tool. Just keeping working at it. It’s well worth the effort you put in

now to become more efficent for later.

Fig. 10.6.4:

Selecting the bird with the Quick Selection tool. This selection

was made

in about five seconds by sweeping a medium-sized selection brush within

the interior of

the bird. Some additional work remains, however, since a few

parts of the bird remain

unselected, and a few pixels outside the bird (the berry behind it)

have been selected.

These finer-scale adjustments can now be made using a finer-scale

selection brush.

You’ll want to zoom in (using cmd+ or ctrl+) to make those fine-scale

adjustments.

Once you’ve got

the bird selected, it’s a good idea to either save that selection or to

copy the bird to a separate layer (or both). Choosing menu option

Select and then Save Selection allows you to store

this selection under a specified name, so that you can call it up again

later, if needed (via Select >

Load Selection). Alternatively, you can press cmd-J on a

Mac (ctrl-J in Windows) to

automatically create a new layer containing

only the contents of the selection. Each of these two options has

its own advantages. Saving a selection is slightly more

flexible than creating a new layer, because when you call up the

selection later you’re free to modify the selection boundaries if

needed. Also, when saving into a Photoshop file (*.psd), a saved

selection will take up less space than an additional layer.

Layers, on the other hand, have some advantages of their own.

Once you’ve created a separate layer containing the bird, you can apply

other processing filters (e.g., altering the saturation, sharpness, or

contrast) to just that layer; a single click of the mouse then allows

you to turn that layer on or off, thereby allowing you to rapidly

assess the overall effect of the modifications you’ve made to that

layer (relative to the original pixels in the underlying base

layer).

For especially difficult subjects I sometimes resort

to the Quick Mask mode, which

is activated by clicking this icon in the tools palette:

Note that Quick Mask is a mode,

not a tool. Once you’ve

activated this mode, you need to select the Brush Tool, which will now

be set to paint in red (which is why in previous tutorials I’ve

referred to it as the Mask of the

Red Death*). Anything

that you

paint red in Quick Mask mode will be enclosed in a selection when you

transition out of Quick Mask mode (or, depending on how you have the

tool set up, it may be the parts not

painted red that end up being selected—but in that case you can then

invert the selection via Select >

Inverse). The figure below shows a

sloppy attempt to paint a bird red in the Quick Mask mode (note that

the berries are naturally red, and haven’t been selected).

Fig. 10.6.5:

Selecting the bird using the “Mask of the Red

Death” (Quick Mask).

Simply paint the bird with the Brush Tool. If you make a mistake,

switch colors

and unpaint the mistake. When you leave the Quick Mask mode,

everything

you’ve painted red will be selected. The actual color used to

depict the mask, as

well as the behavior of the mask—i.e., whether it is the painted

regions or the

unpainted regions that are selected—can be specified in the Quick Mask

Options window (double-click the Quick Mask icon to show this window).

If you accidentally paint outside

of the bird, you can very quickly fix your mistake by pressing the “X” key (which swaps the foreground

and background painting colors for the current brush) and then

un-painting the area you mistakenly painted; alternatively, you can use

the Undo feature in Photoshop

by pressing ctrl-Z or ctrl-shift-Z.

When the Quick Mask icon is clicked a second time,

the regions that have been painted with the Quick Mask brush will then

be enclosed in a selection boundary, just as if they had been selected

with one of the standard selection tools. The advantage of the

Quick Mask

tool is that it allows you to (more easily) specify what I call fuzzy boundaries. Imagine an

image in which part of the bird fades into the background. The

exact boundary between the bird and the background in that region may

be entirely imperceptible. If you were to arbitrarily impose a

selection boundary where you imagine the contour of the bird to lie in

this region, and then apply some digital processing which makes the

bird stand out more from its background (e.g., making it darker, or

more saturated), the effect in the region of

ambiguity between the bird and its background will often be to produce

an unnatural-looking contour that many viewers will quickly perceive as

an

artifact of digital manipulation. In other words, it won’t look good.

In these cases it’s possible to instead use a

soft-edged (rather than hard-edged) brush in the Quick Mask when

painting the bird red, so that you can effect a smooth selection

gradient in the region of ambiguity between the bird and its

background. When you switch out of Quick Mask mode you’ll see a

selection contour that looks just like any other, but Photoshop will

remember that the selection in the ambiguity region follows a gradient,

and will respect that gradient when applying digital effects to the

selection, and/or when blending a layer created from the selection with

layers beneath it. All you need to do is to modify the Hardness slider in the brush’s

attributes pane so as to achieve the desired fading radius. You

can also modify the Opacity setting for the brush, to achieve a similar

effect; some experimentation with these two settings (Hardness and

Opacity) in the context of a standard paint brush in Photoshop will

give you some intuition for how these work in practice. Yet

another option is to use Select >

Modify > Feather and to choose an appropriate Feather Radius to give you the

degree of fade-out for your selection that you desire.

Note that you can seamlessly switch between

selection

tools. For example, I often begin with the Quick Selection tool,

and then switch into Quick Mask mode to refine the selection.

When you go into Quick Mask, any region that’s currently selected will

appear red (or, depending on your settings, it may be that regions not selected will appear red—or

some other mask color that you have set). After refining the

selection in Quick Mask mode you can leave that mode and then further

tweak the selection using any of the other selection tools. Any

selection tool can be set to the “add” or “subtract” mode to allow modification of the

current selection, so you can switch between selection tools at will

when working on a particular selection.

In your quest

to make the bird stand out from its background, it’s sometimes more

productive to concentrate on modifying the background rather than the bird;

you might therefore want to select the background, or some

part of the background, rather than selecting the bird itself.

When the background consists of a narrow range of colors (a sky, for

example), there’s an easy way to select the background which often

either gives you exactly the selection that you want or something close

enough that you can then modify that selection easily using the tools

described above.

Fig. 10.6.6:

Selecting a color range in an

image. This is often useful for selecting the

background of the image. Remember that

you can always invert a selection via the

menu option: Select > Inverse.

As shown in the figure above, it’s

a simple matter to invoke the Select

> Color Range menu option, which then brings up the Color

Range

dialog box shown below. The first thing you need to do when the

Color Range box appears is to move your mouse cursor out of the Color

Range box and to click it on some part of the visible image that

contains the

color you want to select. As soon as you do so, all pixels in the

image which more-or-less match that color will be selected, and will be

temporarily masked

out in red (or, depending on how you have the brush color or Invert selector set, all the pixels

not of that color

may be masked in red).

Fig. 10.6.7:

Selecting the background via the Color Range tool. The Fuzziness

parameter controls how aggressively Photoshop will include other colors

similar

to the one you’ve selected. By holding the shift key when

clicking on the image you

can add additional colors to those already selected via previous

clicks.

By turning up the Fuzziness

setting you’ll allow Photoshop to also

select pixels that are of a color similar to the one you’ve clicked on,

with the required degree of similarity being indicated by your

Fuzziness setting. Note that you can also hold down the shift key on your keyboard and

click on additional pixels to add to the set of colors that you want to

be selected.

Fig.

10.6.8:

The result of using Color Range. After pressing the OK button,

the Color

Range window goes away, and the masked regions (or their inverse) are

selected. In

the example above, you can imagine how much more difficult it would

have been to

select the given regions manually, using the mouse cursor.

The reason this tool is useful for selecting backgrounds (especially

skies) is that out-of-focus backgrounds often contain a restricted set

of colors, which you can rapidly select via this tool. Once you

press OK in the dialog box (or the enter

key on your keyboard), the red

mask is replaced by a familiar dashed-line selection boundary, as shown

in the figure above. In this particular case you’ll notice that

some parts of the background have been omitted from the selection, and

a few pixels in the bird have been included; this can be quickly

corrected

using the Quick Selection tool or the Quick Mask

mode.

There are a number of other things you can do with

selections that you might occasionally find useful. For example,

the Select > Modify > Expand

and Select > Modify > Contract

options allow you to automatically expand or contract your selection by

a specified number of pixels in the appropriate direction.

Expanding or contracting the selection in this way can be useful in

conjunction with the Feather

feature (Select

> Modify > Feather), since you may want to feather

outward or inward from the selection you’ve already obtained. Yet

another possibility is to convert a selection into a layer mask, which

effectively masks out regions of the current layer so that pixels from

lower layers can show through. Layer masks tend to be wasteful

(in terms of memory use and file size), but often provide much greater

flexibility in terms of being able to make later adjustments.

Layer masks are addressed in greater detail in Chapter 13.

Another use of Expand

and Contract is to rapidly

eliminate large numbers of tiny “holes” in your selection, such as may

occur when selecting via Select >

Color Range. Rather than sweeping these little “holes” out via a selection brush, you

can simply Expand by some

number of pixels and then Contract

by the same number of pixels. This should close up any holes of

sufficiently small diameter, without too drastically altering your

selection otherwise (though it will tend to smooth your selection

boundary). Along a similar vein, beware of tiny “islands” of selection that may remain

after you deselect a region that the Quick

Selection tool incorrectly selected; these little islands of

selection may escape your attention when you’re creating the selection,

but later can become more obvious if drastic exposure adjustments are

made to the selected pixels. Checking for these superfluous

selection islands can be done by (temporarily) creating a layer mask

for the current layer from the selection, and then holding the Option / Alt key while clicking on the mask

with the mouse cursor; this will display the layer mask at high

resolution in the main image area, so you can check for small islands

of black pixels representing selection islands that you don’t

want. Alternatively, you can simply Contract your selections by some

small number of pixels (say, 10) and then Expand by the same number, to

ensure that features smaller than this diameter will be automatically

deselected.

It’s worth keeping in mind that for many

applications you needn’t obtain the most perfect selection that

separates, with 100% accuracy, pixels of the bird from the non-bird

pixels around them. Though sometimes it’s possible to obtain

nearly perfect selections using the Quick

Selection tool, in many other cases you’ll find it requires

rather more work. For images that you intend to print on large

media, it may indeed be worthwhile for you to magnify an image to 100%

zoom and then spend the time painstakingly adjusting the selection

boundary to achieve perfect separation between the bird and non-bird

pixels. For images to be posted on the internet, this is rarely

necessary. Even for images to be printed large, imprecise

selection is often still acceptable, especially if you’ll be feathering

the selection anyway. For bird photographers who take thousands

of images at each outing, imprecise selection during postprocessing is

a matter of practicality. Many of the transformations you’ll

apply to a selected region (such as sharpening or de-noising) can be

done using only quick-and-dirty (i.e., imprecise) selections.

Knowing which selections need to be precise is something that will come

to you with practice (as will knowing how much feathering to apply, and

related decisions). Just keep in mind that when processing the

bird separately from the background you’ll want to make sure that no

part of the selection extends beyond

the actual boundary of the bird.

Note that once you’ve selected part of an image via

the selection tools, you can then apply just about any processing

filter

in Photoshop to just that part of the image. For example, if

after selecting

the bird you then invoke the Hue/Saturation

window, you’ll find that

the

adjustments you make in that window will affect only the bird (or any

other part of the image which is currently selected). As we’ll

see later, this is an extremely powerful and efficient technique for

improving the

aesthetics of an image.

Finally, note that the decision of whether to apply

filters to a selection directly, or to first convert the selection to a

layer, needn’t be an “either-or” proposition. Because

creating and deleting (or merging) layers is so quick and easy in

Photoshop, it’s often convenient to go back and forth between them as

needed. What I typically do is as follows. First, I create

my selection, usually using the Quick

Selection tool. I then save the selection to a named

channel (Select > Save Selection).

The selection stays active after saving it, so I can simply press Cmd-J on my Macintosh to make a

layer out of the selected pixels. The selection goes away at that

point, so the “marching ants” (dashed line indicating the

selection boundary) are gone and will no longer distract me. I

then invoke the desired filter to bring up its parameter window, and

make sure the Preview box is

checked, so that the effects of parameter changes are updated

instantaneously. With the marching ants out of the way, I can

concentrate more easily on the overall aesthetics of the image and how

my impression of the image changes as I move each parameter

slider. Once I’ve finished setting the parameters and have

applied the filter, I then merge the temporary layer back into the

underlying layer that it came from (by right-clicking the mouse on the

layer in the Layers panel and

selecting Merge Down, Merge Layers, or Merge Visible, as

appropriate).

If later I decide the same region needs

additional processing, I can easily call up the same selection via Select > Load Selection and then

proceed according to the same series of steps. By not keeping

these temporary selection layers around indefinitely, I’m both saving

memory and disk space and also keeping the Layers panel uncluttered.

This also avoids the potential for confusion later: keeping too many

layers can complicate further processing, since you need to put more

mental effort into keeping track of which layers are on top of which

others, and which layers you want to select from, when making new

selections. With saved selections, you can re-create a layer for

a selection at any time, as needed.

*If

you double-click the Quick Mask icon you should see a dialog box

containing a number of parameters, one of which allows you to use black

or white as the masking color rather than red; you can also dictate

whether the painted regions, or, alternatively, the unpainted regions,

are to be

selected when transitioning out of Quick Mask mode.

|