|

10.3

Image Layers

As will be explored in much

greater detail later in this book, an extremely powerful method of

improving the visual impact of bird photos is to process the bird

separately from its background, to make the subject stand out more

prominently. More generally, it’s often highly desirable to

process different parts of the image differently—for example, to darken

one part of an image while lightening another, or to sharpen the

subject while blurring the background, etc. In many cases (though

certainly not all), this is best accomplished via the use of image layers.

Layers in photoshop are a lot like layers in a layer

cake. If you imagine a layer cake in which the layers are

different shapes and colors, and if you imagine looking down on the

cake from above, you can envision that the top layer will eclipse a

certain portion of the layers beneath it, but that some parts of those

lower layers may be visible nonetheless, if they “poke out” around the edges of the top layer

(and any other layers above them).

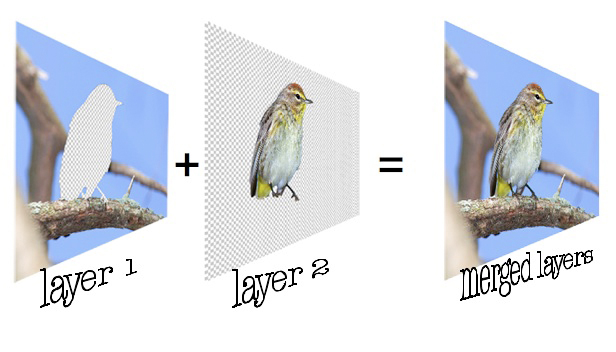

The figure below illustrates this more concretely in

the case of bird photography.

Fig. 10.3.1:

Layers in Photoshop. Separating elements of the image

into different layers is convenient because it affords much greater

efficiency when applying effects intended for only one part of the

image. Merging the layers then produces a complete image.

In this case, we’ve partitioned the original image into two layers:

layer 2 contains all of the pixels making up the bird, while layer 1

contains everything else. If you were to merge these two layers

together, you’d get back the original image. The reason it’s

useful to separate image elements into separate layers is that it makes

it very convenient for when you want to apply any sort of digital

manipulation (e.g., adjusting the sharpness, exposure, saturation,

contrast, etc.) to just the bird, or just the background, or to some

other important element in the photo which naturally stands by itself

or perhaps simply requires the most extensive processing.

Making layers is easy in Photoshop. Once

you’ve got some important part of the image selected (selection is discussed section

10.6), you can make a new layer

containing just that part of the image

by pressing Cmd-J on a Macintosh computer (Ctrl-J on a Windows

PC). A new layer will be created and can be selected by clicking

on it in the layers panel

(typically located near the lower-right part of the screen). The

figure below shows a typical layers panel. In this example we’ve

created four layers: a text layer (for signing the photo), a cloud

layer (for adding some artifical clouds in the background), a

background layer, and the full image which includes the subject (named

here “Background” because that’s the default name

assigned by Photoshop to the original layer comprising the entire

image).

Fig. 10.3.2:

The Layers panel in Photoshop. Layers can be

renamed, moved higher or lower in the stack, toggled off

and on, given layer masks that make parts of a layer

transparent, blended with other layers in various ways,

and made semi-transparent to any integral degree.

The layers panel has a number of powerful

features. First, notice the eyeball icons to the left of each of

the four layers in the figure above. Clicking on any of these

will cause that layer to toggle between the visible and invisible

states. This is especially useful for special-effect layers,

because you can repeatedly toggle the layer on and off until you decide

whether the image looks better with or without that effect. In

the upper right corner of the layers panel you’ll see that there’s an opacity setting, which can be set

differently for each layer. When the opacity is less than 100%,

the layer becomes semi-transparent; this is useful for special-effect

layers that might look overly gaudy or artificial at 100% opacity, in

which case a lower opacity might produce a more tasteful degree of

subtlety. The blending mode

(upper left corner of the panel) is a powerful tool that I almost never

use, but that can come in handy in rare cases.

The “add a mask” button along the bottom of the

panel creates what we call a layer

mask, which shows up as an additional icon in the layer

bar. This is a very powerful tool which takes some experience to

master but can save considerable time once you’re comfortable using

it. The mask is a pattern that determines which parts of the

layer are visible, and which are (fully) transparent. You can

select the mask and paint on it using the brush tool (section 10.1).

Any region of the mask that you paint in black causes the corresponding

part of the layer to become transparent. The nice thing about

masks is that if you make a mistake, you can easily fix it by switching

your brush color between black and white and re-painting that part of

the mask. You can also use shades of gray to indicate partial

transparency. Masks facilitate one form of nondestructive editing, in which

edits that you made previously can be easily changed later by simply

re-painting parts of the mask. They’re especially useful for

blending only part of a layer with other visible layers, by painting

the mask in various shades of gray (such as via the gradient tool—section 10.1).

The figure below shows just one of the many useful

things you can do with layers. In this case, we’ve created a

special layer with artificial clouds rendered by Photoshop’s built-in

cloud effect. The top image shows the result of enabling the

cloud layer, while the bottom image shows the result of disabling the

cloud layer. By repeatedly toggling the layer on and off, the

pros and cons of utilizing the layer in the final image can be assessed

visually without having to rely too much on imagination.

Fig. 10.3.3:

Assessing a special effect via layer toggling. Top: an

image in which an artificial cloud layer is toggled on. Bottom:

the

same image with the cloud layer toggled off. The ability to toggle

layers like this on and off significantly eases the task of assessing

the aesthetic value of various processing options.

Note that images that contain layers should ideally

be saved in Photoshop’s proprietary PSD format, to retain the maximal

amount of information. In order to export the image to JPEG

you’ll need to flatten the

image (either permanently or temporarily), which simply means that you

need to merge the layers into a single composite image. I

recommend keeping both the original RAW file from the camera and the

PSD file containing any layers you’ve created, in additional to any

flattened JPEG’s you’ve extracted from the PSD file. The JPEG’s

are useful for posting images on the internet or for making paper or

canvas prints. The PSD’s are useful if you need to touch-up some

part of the image (e.g., if after printing the image you find that the

bird doesn’t stand out from the background enough), or if you need to

extract additional JPEG’s at different resolutions. The RAW files

should, in my opinion, never be deleted, since you never know when you

might find some flaw in a processed image that can only be fixed by

going back to the RAW image and re-processing it from scratch.

One disadvantage of the use of layers is that each

additional layer requires more memory (and hard drive space) to store,

and can slow down your computer if you use too many of them. This

problem can be partially alleviated by installing more RAM (memory)

into your computer, though disk space remains an issue.

As we’ll see in section 10.6,

a simpler, quicker,

and somewhat less powerful alternative to layers is the use of saved selections. The ideal

balance between the use of these various techniques (i.e., layers

versus saved or de novo

selections) is one which each photographer needs to find based on his

or her own postprocessing style and hardware.

|