|

12.5 Separation

of Subject

As has been noted numerous times

in this text, the ability to separate the subject from its background

before applying digital enhancements to an image is probably the most

powerful “darkroom” technique available to today’s

wildlife photographers. In Photoshop, this can be accomplished

very easily in many cases via the use of the Quick Selection tool. In

section 10.6 we outlined a number of

techniques for precisely selecting

the bird using the powerful tools provided by Photoshop. For some

bird photos, selecting the subject can still be quite difficult,

however, particularly if there are branches or leaves partially

occluding the bird; legs and beaks and tails often complicate matters a

bit as well, since they’re usually thinner and of a different color

than the rest of the bird. Nevertheless, even in difficult

situations it’s often worthwhile to put in the effort to separate the

bird from its background, so that the subject can be processed

separately from the rest of the scene.

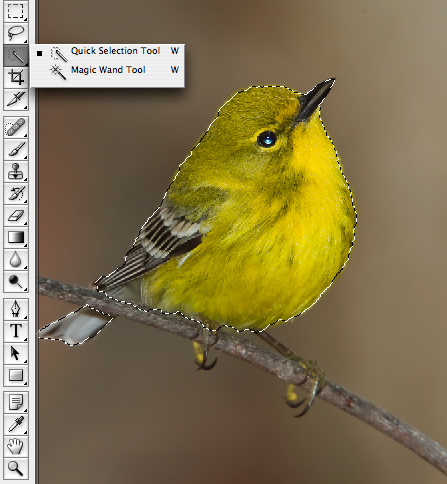

Fig. 12.5.1:

Separating the subject from the background is one

of the first tasks to be performed in my own workflow. This allows

me to adjust the brightness, sharpness, and saturation of the

bird differently from the background. This can be useful not

only for correcting visual defects in the subject, but also for

making the bird stand out more (or perhaps less).

As we described in section 10.6,

simply selecting the bird via one of Photoshop’s standard selection

tools may not be sufficient for the types of subtle processing that

you’d like to apply. In particular, it’s often a good idea to feather the selection via the Select > Modify > Feather

menu option, so that the selection has a soft edge. When the

selection is given a soft edge in this way, any processing that is

applied to the selection will gradually fall off in intensity around

the borders of the selection; this can help to reduce unnatural

boundary effects, especially for filters involving brightness or

blurring. Prior to feathering you’ll often want to contract the

selection via the Select > Modify

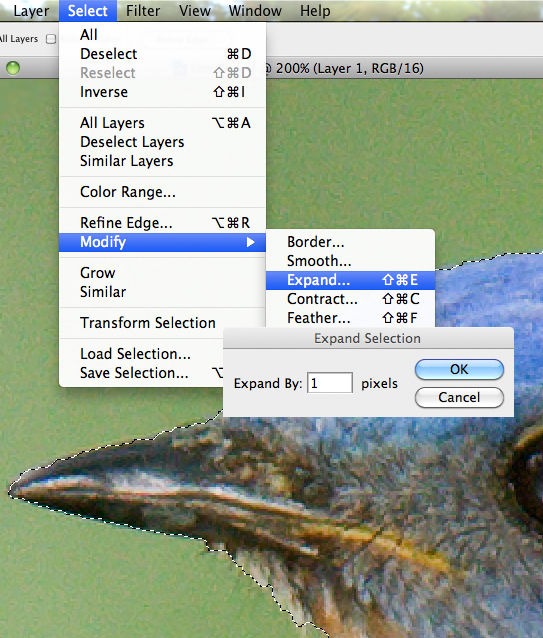

> Contract menu option. The figure below illustrates

the related task of expanding the selection.

Fig. 12.5.2:

Depending on what kind of processing you’re about

to apply to the bird, you may want to expand or contract the selection

by a few pixels, and to apply some feathering, to supress any edge

artifacts that may occur as a result of further processing.

Once you’ve got

the bird selected, the next thing you should do is save the selection

to a named channel, via the Select > Save Selection menu

option. Saved selections are saved in the PSD file when you save

your work, so they’ll be available during subsequent post-processing

sessions on the same image. You’ll typically want to first save a

non-feathered version of the selection, since you can always re-load

the selection from memory and feather it as needed, whereas

un-feathering a saved, feathered selection is rather more

difficult. You can, of course, save multiple versions of a

selection (such as a feathered and a non-feather version, or versions

feathered at different radii) by simply creating different channel

names when saving the selection.

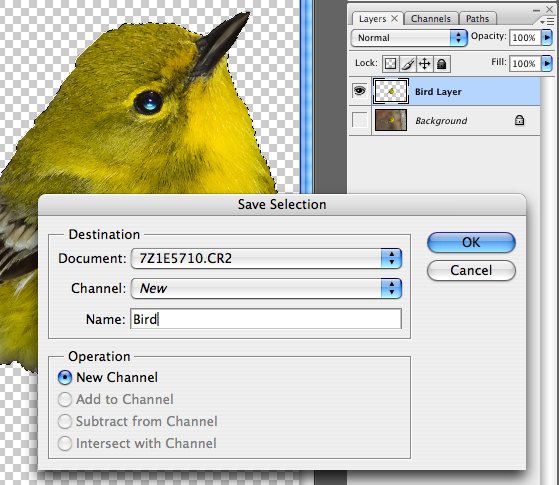

Fig. 12.5.3:

You should always save any nontrivial selection

into a new channel, so you can recall it later. Once you’ve

saved the selection, you can then either apply processing

directly to the selected area, or first copy the selected area

to a new layer.

After saving the selection of the

bird, you can then either apply processing filters directly to the

selection, or duplicate the selection into its own, separate layer (by

pressing Cmd-J / Ctrl-J).

There are many advantages to creating a separate layer for the bird;

just about the only disadvantage is the increased memory space required

to do so, though on most computer systems this won’t be a practical

limitation (though your file sizes will also increase, and this may be

more of a limitation for you if your hard drive is almost full).

Once you’ve separated the bird and its background

into different layers, you’re then free to process those layers

differently by simply clicking on a given layer before invoking any

image processing filters or painting tools. Once you’ve got a

part of the image separated into its own layer, you can then select

parts of that layer (with the standard selection tools) and copy those

parts to layers of their own, if desired. For example, once

you’ve got the bird on its own layer, you can then separate out the

face, the chest, the wings, and the tail all onto their own, separate

layers, and then process those layers differently. One reason for

doing so is to be able to correct local lighting deficiencies that

affect specific parts of the bird. For example, when using flash

to illuminate warblers, I often find that the highly reflective flight

feathers often result in feather glare that I then need to fix in

postprocess. I do this by selecting just the part of the bird

exhibiting the glare and then applying the Highlights tool to reduce the

glare. Conversely, some parts of the bird typically end up less

well lit than others, and for these parts I like to apply the Shadows or Levels tool to dispel the shadows

and create the impression of more even lighting. Though these

operations don’t always require that parts of the bird be selected

before applying the adjustment, doing so often provides for greater

control and reduces unintended side effects on other parts of the image.

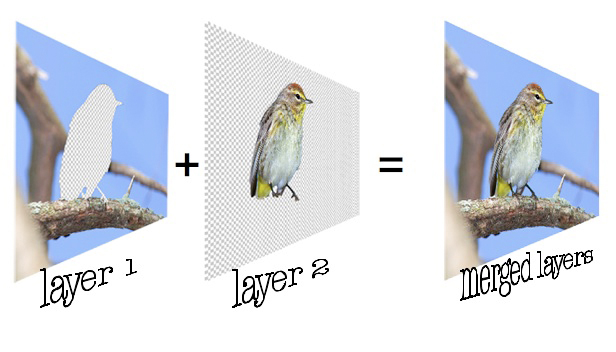

Fig. 12.5.4:

Once you’ve separated the bird and the background

into different layers, you can apply different processing to them,

allowing you to adjust how strongly the bird stands out. The use

of layers requires more memory, but affords enormous flexibility.

Keep in mind that while we talk

about “separation of the subject”, what we really mean in many

cases is separation of the foreground

from the background, where

the foreground will typically include not only the bird but also its

perching substrate. The perching substrate will, of course,

typically be in focus just as well as the bird, so attempts to

de-emphasize that substrate (by processing it the same as the

background) may result in an unnatural effect that is apparent to the

viewer. However, because the perching substrate will almost

always have a different texture and color than the bird itself, it’s

typically worthwhile to separate the substrate from the bird, so that

you’ll generatelly want to parse the image into three parts: the bird,

the in-focus portion of the perching substrate, and the out-of-focus

background.

Fig. 12.5.5: An

example of differential processing of foreground

and background. Left: the original image. Right: after

rendering

clouds into the background. The sky was selected via Color Range

and then duplicated twice; one copy was brightened and the other

darkened. Render > Clouds was then applied to a layer mask on

the top layer, allowing the brighter lower layer to show through

as clouds. The whole process took about two minutes.

Note that for

many purposes (especially when preparing images to be posted on the

internet in low-resolution), you won’t necessarily need to separate the

subject from the background with exacting precision; we already alluded

to this in some sense when discussing the issue of feathering.

Since birds are three dimensional and the imaging plane is

two-dimensional, the borders of the bird will often look acceptable if

they’re less distinct than the main part of the bird (especially when

the depth-of-field is razor thin). For this reason, it’s often

possible to get away with a selection boundary that only roughly

follows the precise outline of the actual bird. For some

applications, you’ll want that selection boundary to fall completely

within the bird, while for others you’ll want the boundary to

completely contain the bird.

As noted earlier, it’s often desirable to create

multiple versions of the bird’s selection, to use for different

purposes. These different versions can often be obtained from a

single initial selection, via some combination of Contract, Expand, and Feather operations applied to the

original selection. You can also use the Select > Inverse operation to

obtain a selection of everything except

the bird. Note also that feathering can be performed by going

into Quick Mask mode (by

pressing the Q key) and using

a soft-edged brush with reduced opacity to paint a gradient around the

boundary of the selected region; this technique can be more difficult

to use effectively, however.

If you’re going to be creating a new layer from the

selection, it’s sometimes best to err on the side of including too much

of the subject in the new layer—i.e., using a hard boundary rather

than feathering it. Once you’ve got the subject on its own layer

and have applied some adjustments to it (e.g., color, brightness,

sharpness, etc.), you can then use a layer

mask (see chapter 13) or the Eraser

tool to soften the edges of the layer (using a soft edge and

reduced opacity in both cases). Blending the modified subject

back into the scene in this way requires more work, but has the

advantage that you get instant visual feedback and can adjust your

handling of the tool accordingly. By contrast, the use of Select > Feather would normally

be applied prior to any qualitative adjustments to the subject, so you

won’t know until later whether you’ve chosen an appropriate feathering

radius. An added advantage of using a layer mask to do the

blending is that it can always be adjusted again later if you apply

additional processing to either the subject or the background

(obviously, either could affect the blending of the bird into the

scene).

|

|

|