|

5.6 Image

Processing Software

While instruction in the use of

image processing software is deferred to Part III of this book, here we

will very

briefly consider some of the issues involved in selecting such a

software package, including a survey of the important features offered

by various packages, as well as some advice regarding compatibility

issues.

The most popular option (among those who can afford

it) is obviously Adobe’s well-known Photoshop

program, which has a

well-deserved reputation for being extremely powerful, though also

somewhat difficult to learn how to use. Of the competing

commercial products comparable to Photoshop, the most prominent is

probably

Corel’s Paint Shop Pro, or PSP. While PSP does appear to

offer

most or perhaps even all of the essential features used by casual

Photoshop users, and at a seemingly far reduced price (under $100 US

for PSP, versus many hundreds of dollars for Photoshop), PSP is

currently available only for use on Windows

machines (i.e., on PC’s, but not

Macs). Furthermore, while the full version of Photoshop is indeed

extremely expensive, the “lite” version, called Photoshop Elements, is nearly the

same price as PSP, and is available for both Windows and

Mac systems. Also, students and others affiliated with

educational institutions can get the full version of Photoshop at a

fraction of the price that the general public pays. I paid about

$200 for my copy a few years ago, instead of the full $600, since I

work at a university. Though I previously used Photoshop

Elements, I did find that the additional features included in the full

version (called Photoshop CS3,

which has now been upgraded to CS4)

did occasionally come in handy.

Regarding the use of competing products, keep in

mind that as the industry standard, Photoshop is much better

documented, via internet-based tutorials and the like, than competing

programs such as PSP. There are untold numbers of Photoshop

tutorials available for free on the internet, showing in detail how to

achieve the most amazing visual effects. There are also many

add-on products from third-party software companies (so-called “Photoshop Plug-ins”) that seamlessly integrate with

Photoshop and

extend its functionality in various ways (such as more intelligent

noise-removal algorithms). Many free plug-ins are available as

well.

For those readers with recently-purchased Canon or

Nikon DLSR’s, there is another, far more economically palatable option

than either Photoshop or its various commercial

competitors—namely, the free software that came bundled with your

camera. In the case of Nikon cameras, this would be View NX,

while the Canon product is called DPP

(for Digital Photo Professional).

Fig. 5.6.1: An

OEM photo processing program: Canon’s “DPP” (Digital Photo

Professional).

Nikon has a comparable product called Capture/NX2. Although far

less powerful than

Photoshop, these programs let you adjust the sharpness, saturation,

contrast, brightness,

and color balance of your photos. They don’t allow complex

editing, such as erasing

a stray branch, or separating the foreground from the background.

These free programs from camera manufacturers are

obviously not meant

to compete with the likes of Photoshop and other commercial products,

but for many casual bird photographers, they are probably quite

adequate. In fact, there is one aspect of these OEM (original equipment manufacturer)

products

which can potentially outperform all competing products, and that is

the OEM software’s RAW-conversion

engine. Though we’ve not yet

discussed RAW files, they’re

the files with the most image information

(as compared to inferior file formats such as JPG) that are exported by

your camera onto the memory card, and must be read in by whatever

image-processing software you opt to use. Since each camera

manufacturer uses their own proprietary RAW file format (e.g., CR2 for

Canon, NEF for Nikon),

software companies without an explicit business

relationship with the camera manufacturer have to reverse-engineer that

company’s RAW file format in order to be able to work with it in their

software. Since the OEM will generally have a more perfect

understanding of its own file format, the RAW conversion engine

produced by that OEM can be exepected (usually—though not always) to produce the

highest-quality conversions (i.e., from RAW to JPG or other target file

format) of their RAW files.

If you spend any significant amount

of time lurking in online photography tech forums like dpreview.com or fredmiranda.com,

you’ll see that the true zealots will always insist

that systematic comparisons between competing cameras’ images be

done via their RAW files and using only the appropriate RAW

converters. A poor RAW converter may result in image artifacts

such as moire patterns, and potentially

other issues affecting image quality, so this is a factor worth

considering

when shopping for image processing software. It is, of course,

possible to use any arbitrary RAW converter to convert your files to a

common format such as TIFF or JPG, and then to import these converted

files into whichever editing software you elect to use, though it’s

much more convenient when your editing software can do the RAW

conversion itself, since this simplifies your workflow. Photoshop

in particular is very convenient in this regard, and though not

everyone agrees that Photoshop’s RAW converter is the best, I’ve found

it to work exceptionally well for my photos.

Yet another option—and I personally did this for

several years—is to simply use the built-in or bundled software that

came packaged with your computer’s operating system. In the case

of Mac systems, there is a program included in all current

distributions called “Preview”, which is intended largely as a

utility

for viewing images as well as other types of documents (e.g.,

PDF files). This program also includes a very limited set of

image

manipulation functions, including adjustment of brightness, saturation,

contrast, and sharpness, as well as a primitive but surprisingly

effective method for performing color correction (e.g., fixing images

in which parts that should be white actually look yellow).

Unfortunately, it doesn’t include any noise reduction functionality.

Fig. 5.6.2: The

“Preview” program that

comes standard with Apple’s “OS X” operating

system;

a comparable utility is available for Microsoft’s “Windows” operating

system. These programs

alllow basic but rapid adjustment of image properties, such as

brightness, sharpness, contrast,

saturation, and color balance.

One very large advantage of programs like Preview (and whatever happens

to be its current counterpart in the Windows

world) is the speed with

which you can use it to process very large numbers of images. By

double-clicking a file with the mouse, I can bring up Preview on my

Mac, and then with a few quick adjustments to sliders on the Image

Correction panel, I can typically get a photo very close to its

optimal

settings for publication on the internet (i.e., as low-resolution

images on web pages).

For those who take lots and lots of bird photos but have very limited

time for adjusting the images prior to posting them on the internet,

simple solutions like Preview can be ideal (especially when they’re

also free).

What simple programs like Preview can’t do is to

permit detailed manipulation of specific parts of an image, and this

type of manipulation turns out to be desirable in more cases than you

might imagine. A simple but highly representative example is the

selective removal of noise from parts of an image. As described

previously, noise is typically much more noticeable in smooth

background regions than in the foreground (i.e., in the bird).

Although most commercial software packages provide for noise removal,

they typically also result in a reduction of detail in the subject,

which is especially noticeable for highly detailed subjects like

birds. Thus, a very common workflow for processing bird images is

to

first separate the bird and its background into different layers, and

then to apply the noise-removal filter to only the background layer of

the image, so that the parts of the image with noticeable noise are

cleaned up while the subject retains all of its original detail.

These types of manipulations tend to be either impossible or extremely

laborious in many software packages, whereas in Photoshop they can be

extremely easy, due to Photoshop’s advanced tools for separating

foreground subjects from their background.

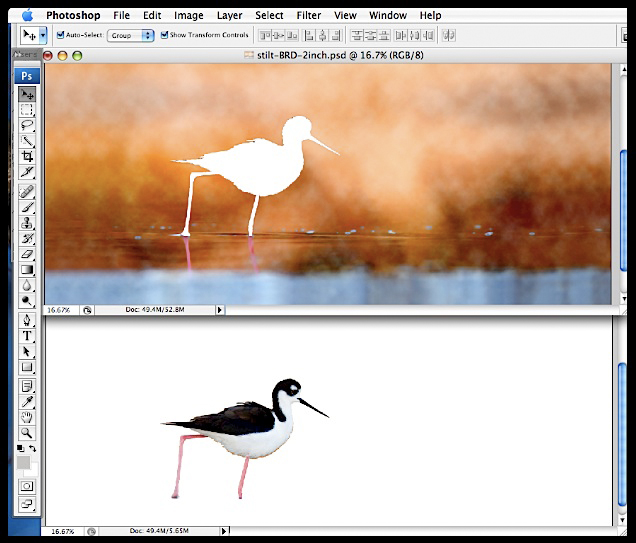

Fig. 5.6.3: Separating the foreground from the background in Photoshop.

Differential processing of the bird and its environment is one of the

most powerful

techniques in bird photography postprocessing. Just the ability

to selectively reduce

noise in parts of an image arguably justifies the high price tag of

Photoshop, since

it arguably offsets much of the value offered by more expensive cameras

boasting

lower noise output.

In Part III of this book we’ll show in great detail how

to perform many image processing tasks in Photoshop.

|

|

|