|

2.4 Brands

There are two very good reasons to

take brand into consideration

the next time you buy a digital camera. First, as in other

technological arenas, the camera companies with the most capital

invariably have greater research and development resources to bring to

bear in developing their product lines, and their cameras will

therefore tend to offer the best image quality, though they may also

have a higher price tag. Second, and perhaps even more

importantly, the more established brands will almost certainly have a

more extensive selection of lenses, and those lenses will also tend to

be better than those of smaller companies, on average. In this

section we’ll briefly review the brand landscape of DSLR manufacturers.

2.4.1

Leading Brands as of Today

As of today, the most popular

brands among bird photographers are Canon, Nikon, and Sony. If you

survey the most successful photographers of birds and other wildlife,

such as Art Wolfe and Arthur Morris, you’ll find that the vast majority

of them use one of these brands. Other companies occasionally

come out with individual products that promise to rival those of the

big three, but for bird photography the wisest choice seems to be to stick with one of the major brands that offer both

state-of-the-art cameras and a wide range of lenses useful for shooting

birds. Below I’ll survey the offerings of Canon and Nikon and some of

the leading second-tier companies; at this point Sony is also a major contender, though I'm less familiar with their products. Though this chapter is about

cameras (lenses are discussed in great detail in Chapter 3), I’ll be

briefly surveying the birding lenses available from these companies as

well, since I believe the lens line of a company is even more important

than their cameras, when choosing a brand for bird photography.

Canon and Nikon

To my knowledge, only Canon, Nikon, and Sony offer both high-quality cameras

and high-quality lenses spanning the range of useful birding focal

lengths from 400mm to 800mm. (As we’ll see in Chapter 3, pro bird

photographers do most of their work in the

400mm-800mm range, with an emphasis on the upper portion of that range—though there are certainly

exceptions). In the case of Canon, this range is more than

adequately covered. At the low end, there are no fewer than four 400mm lenses: the 400mm f/5.6 prime lens, the 400mm f/4 prime, the 400mm f/2.8 prime, and the 100-400mm f/5.6 zoom. (Focal lengths, f-numbers, and the relationship

between the two are all covered in great detail in Chapter 3). Two of

these are highly portable and hand-holdable (the two f/5.6 lenses), while one (the f/4) is hand-holdable by stronger

or more energetic individuals, and one (the f/2.8) requires a tripod unless

you’re a megalomaniac (which a fair number of bird photographers

are). Only the f/5.6

prime lacks image stabilization (“IS”). In the mid-range are the

500mm f/4 and the 600mm f/4, both with IS, and at the upper

range is the ultra-expensive (roughly $11,500 US as of this writing)

800mm f/5.6 lens with

IS. (I won’t bother discussing Canon’s 1200mm f/5.6 lens, since there are only

about 15 in existence, and they cost about $100,000 used).

Canon

|

Nikon

|

100-400mm f / 5.6 zoom

|

80-400mm f / 5.6 zoom

|

400mm f / 5.6

|

|

400mm f / 4

|

200-400mm f / 4 zoom

|

400mm

f / 2.8

|

400mm

f / 2.8

|

500mm f / 4

|

500mm f / 4

|

600mm f / 4

|

600mm f / 4

|

800 mm f / 5.6

|

|

Fig. 2.4.1:

Canon and Nikon birding lenses, as of 2013. The 400mm f/2.8

lenses of both brands are of questionable utility for birds, due to

large size

and low magnification. Canon has a slightly more complete range

of useful birding

glass, though the lenses from both brands are of

exceptional quality, and always preferable over third-party lenses.

Nikon’s current lens line is slightly less

extensive, at least within the useful range of birding focal

lengths. Of the really serious, hardcore Nikon birders I’ve seen

in

the field, the most popular lens has been the Nikkor

200mm-400mm f/4 lens (though

the 500mm f/4 is very popular

too).

This lens has a reputation for being extremely sharp, and though it

weighs

about 8 lbs., some people actually hand-hold it (though it’s not easy

to do so).

Like Canon, Nikon also has 400mm lenses at f/5.6 and f/2.8 apertures.

Unfortunately, for bird photography the 400mm focal length is most

useful for hand-held applications such as BIF (“birds in flight”), and

neither Canon’s nor Nikon’s 400mm f/2.8

is at all hand-holdable for extended periods, unless you’re the

Incredible Hulk. Though Nikon’s 80-400mm f/5.6 VR zoom is easily

hand-holdable, the older version of this lens can

be truly painful to use for birds in flight, since its autofocus

mechanism is extremely slow. However, in the spring of 2013 Nikon

finally upgraded this lens and it is now reported to be excellent

(though expensive); just make sure if you buy it that you are getting

the "G" version, which is the newer one. Nikon does produce

excellent

500mm f/4 and 600mm f/4 lenses. To my knowledge,

they do not offer an 800mm lens, though the Sigma 800mm f/5.6 is available in both Canon

and Nikon mounts.

In summary, given that both companies offer equally

great cameras and equally great lenses at very comparable prices,

either brand should be considered excellent for bird photography (and now that Sony has entered the market in a big way, they should also be considered a major contender).

I personally prefer Canon because of their two other 400mm lenses (the

fixed-aperture f/5.6 and the

lightweight f/4 with

Diffractive Optics), which Nikon doesn’t currently offer. But

otherwise Nikon is fully as good as Canon in the quality of their

cameras and lenses, and in some cases may be better (though the two

companies tend to leap-frog each other every few years).

The Others

Among the other brands of DSLR available today, only a few others even

warrant mention here. Besides Canon and Nikon, the only other

brands I think I’ve seen actually used in the field by really serious

bird photographers are Sony and Olympus, with Sony in particular releasing a number of very impressive cameras recently.

2.4.2

The Issue of Quality Control

No matter which brand you end up

going with, know this: Whatever model of camera you buy from that

company, there is a very real possibility that the individual unit you

get is defective. This is just as true for Canon and Nikon as the

others. Two consumer-grade Canon bodies that I purchased had

defective autofocus modules, and even after sending them back to Canon

for re-calibration (one of which was sent back twice), I felt they were not up to

my standards, and returned them for a refund. Those were, as I

said, cheap consumer-grade models (just slightly over $1000 US).

The case of the infamous Canon EOS 1D Mark III is now well-known: a

$4500 camera with a defective autofocus module, which the manufacturer

initially denied until Rob Galbraith,

a prominent sports photographer,

irrefutably demonstrated the defects publicly and forced the company to

issue a massive recall of its flagship product. Over a year after

the initial recall, the company is now announcing yet another “fix” for

these “professional” grade bodies. Make no

mistake: I love my

Canon EOS 1D Mark III bodies (both of them), and often sleep with one

or both under my pillow, but newer photographers have to realize that

any camera from any manufacturer, even the top-tier manufacturers, can

turn out to be defective.

I’ve heard it said that the reason Leica (or is it

Zeiss?) lenses are so insanely expensive is that the manufacturer tests

each and every lens before it leaves the factory, rejecting any lens

that doesn’t meet its rigorous testing regimen. The story goes

that Canon and Nikon, in order to cut costs, don’t test their lenses until after a lens is returned by a

customer complaining of a defect. Because many customers

are too inept to notice any defects in their lenses, this saves the

company many thousands of dollars by not having to pay workers to test

every single lens that leaves the factory. The residual cost is,

of course, borne by those discerning photographers who find that they

have purchased a defective lens which needs to be returned to the

factory for a week or more for re-calibration.

The moral of the story is: don’t assume that your

brand-new camera (or lens) is defect-free, even if it’s the most

expensive model offered by the most prestigious brand. Spend the

14-day return period aggressively testing the unit, so that you can

return it for a refund if it turns out to be defective. If you

can’t afford to spend the time testing the camera right away, then wait

to buy the unit until you know you’ll have some time to test it during

the return period.

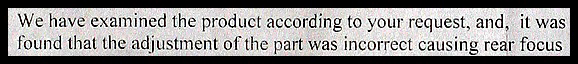

Fig. 2.4.2:

Service Report for a Brand New, Defective Item.

The item, a 1.4x teleconverter, was brand-new. After comparing

images taken

with this unit to those taken with another brand-new unit of the same

exact model,

it was apparent that the first unit was defective. The

manufacturer tested the unit

and agreed it had not been properly calibrated at the factory, and

performed the

calibration free of charge. It now works flawlessly. Don’t

assume a brand-new

camera or lens has been properly calibrated by the manufacturer.

2.4.3

Safe Buying Practices

In addition to being careful as to

which brand of camera you buy, you should be careful in choosing the

merchant you buy that camera from. Make sure the merchant accepts

returns due to defects. Check that the merchant doesn’t charge a

restocking fee. Some merchants have a maximum actuations policy: if you take too

many photos with the unit and try to return it, they may say that the

actuations are too high for the unit to be re-sold, and won’t accept

the return. Check the merchant’s return period; it should be at

least 14 days. Amazon.com

has (last time I checked) a 30-day return period for cameras, and to my

knowledge they don’t check actuations on returned cameras.

If you miss the return period deadline, you’ll have

no choice but to try to resolve your issue directly with the

manufacturer. So far I’ve dealt with two manufacturers regarding

product defects: Canon and Sigma. On the positive side, both

companies were immediately willing to examine the unit for defects, and

in several cases they even paid for shipping both ways. On the

negative side, I’ve found that Canon repair technicians don’t always

fix the problem, though they’ll claim that they made some adjustments

and have “returned the product to factory

specifications”. Others

have reported the same issues, both with Canon and Nikon. The

problem seems to be hit-or-miss, possibly depending on which technician

ends up working on your unit. Just keep in mind when buying new

cameras (or lenses) that it’s best to find any defects during the

return period so you can return the product to the merchant, rather

than having to deal with the (sometimes lengthy) repair process

involved in dealing directly with the manufacturer.

If you’re buying used (which I don’t recommend), you

should first check to see if Adorama

or B&H have the item in

stock in their “used department”, and at the price you’re looking

for. Returning a defective used item to these companies is

generally hassle-free, in my experience. I once returned a 400mm f/2.8 lens that I bought used from

Adorama. It wasn’t sharp enough, in my opinion, and they accepted

it for a full refund, even paying the return shipping. You can

also sometimes find refurbished items at these shops. Factory

reconditioned items typically come with a fairly reasonable warranty

from either the manufacturer or the merchant, which you won’t get if

you buy from some bozo on eBay.

If the reputable camera shops don’t have your item

in their used department, and if you really have to buy used, then

there are other options besides eBay. Although I’ve never bought

a camera on eBay, and have never been scammed by a seller when buying

other items on eBay, I have been (almost) scammed by buyers on that

site, especially by Nigerians. I recommend steering clear of eBay

altogether, either for buying or selling (at least for photography

gear). If you’re a member of any internet photography forums,

check whether any of them have a Buy-and-Sell

board. I’ve heard that buying items on reputable forums such as Fred Miranda’s Buy/Sell forum can

be relatively safe, as long as you do your homework and check the

seller’s post history to see what kind of character you’re dealing

with. There’s also Craig’s List,

though I’ve heard of people getting scammed on there as well. I

personally don’t buy used equipment anymore, because I view buying used

equipment as “buying somebody else’s problems.”

If you do have to buy used, then consider sending

the used item you’ve purchased in to the manufacturer’s service center

to be calibrated. Calibrations of out-of-warranty equipment

generally aren’t free, but I highly recommend having this done, given

all the new equipment that

I’ve seen that needed calibration. Indeed, I’ve heard that some

pros automatically send every piece of gear they buy (even brand-new

cameras and lenses, fresh from the factory) in to the manufacturer’s

service center for calibration as soon as they receive it from their

supplier. If the cost of calibration is an issue, there are some

things, like autofocus accuracy, that you can test yourself, to see if

calibration is needed. In section 3.11

you’ll learn how to check

the calibration of your cameras and lenses, and in section 2.7.3 we’ll

discuss autofocus “microadjust”, for those cameras that support

this

feature.

|

|

|