|

12.7 Sizing and

Signatures

For images that you intend to post

onto a web page or upload to an online photo-sharing site, the last two

things you’ll want to include in your workflow are cropping the image and signing your name. We’ll

consider both tasks in this section.

If the web site that you’re uploading your images to

isn’t your own, you’ll need to find out what restrictions the site

places on image sizes—both in terms of resolution (i.e., number of

pixels along the x and y axes) and the file size (in kilobytes or megabytes). For example, BirdForum.net currently limits its

users to images not larger than 1024×900 pixels and file sizes no

greater than 325Kb (kilobytes). As another example, Flickr.com limits file sizes to

10Mb (megabytes) and 1024 pixels on the longest side (unless you have a

“pro account”). In many cases, if you try

to upload an image that exceeds size or resolution limits, the server

will automatically resize your image; this is generally a bad thing,

because the automatic resizing algorithms used by these servers very

often reduce image quality, so what your viewers see on the site may

not look nearly as good as what you see in Photoshop. By resizing

the image yourself, you retain some control over how the image will be

rendered on the web. If, after resizing the image to particular

dimensions, you notice that the bird now lacks significant detail, you

have the option of cropping closer to the bird and then applying a less

aggressive down-sizing, which will typically result in more subject

detail.

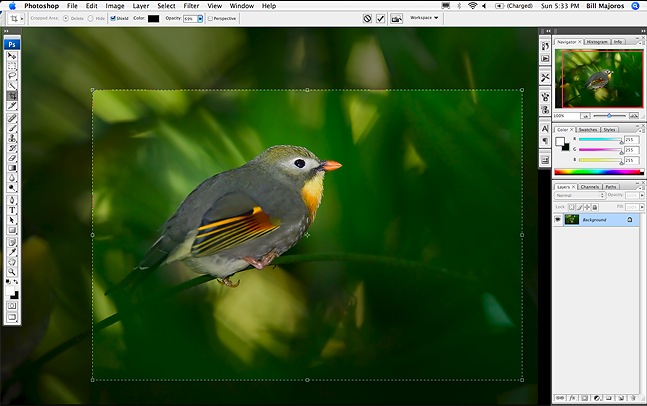

Fig. 12.7.1:

Cropping an image is all about crafting a composition that

presents the bird and its surroundings in a logical and aesthetic

manner.

It also affects the image dimensions and file size, so when preparing an

image for web deployment, you may want to consider several different

options that balance aesthetics against size constraints.

Recall from

sections 8.1 and 10.1

that cropping can be used to as an artistic tool

for re-framing the subject and thereby pursuing a more pleasing

composition. Inasmuch as the act of cropping affects the

aesthetics of the image’s composition, you’ll need to balance the

compositional considerations against the advantage that cropping

provides when you’re facing image size constraints. As with many

things, I personally take an empirical approach to resolving this issue

in my own images: when faced with sizing constraints (whether

denominated in resolution or file size), I try out many different

options for cropping the image, viewing each at the target size and

assessing my feelings for each. If I don’t find any of the

options acceptable, I simply don’t post the image (at that

venue).

The actual mechanics of cropping and sizing of the

image are straightforward in Photoshop. We’ve already discussed

the Crop tool (section 10.1);

the use of this tool is illustrated above in Figure 12.7.1.

Resizing an image in Photoshop is performed via the Image > Image Size option, which

presents a dialog box with various options (see the figure

below). Here you can either specify a resolution in pixels, or a

percentage of the original (e.g., 20% of the original image dimensions,

applied equally to the x and y axes). If you enter only

one pixel dimension, the other will be computed for you automatically

(unless you click on the chain icon, which voids the constraint on aspect ratio). There are a

number of other options in this window, but I personally ignore just

about all of them.

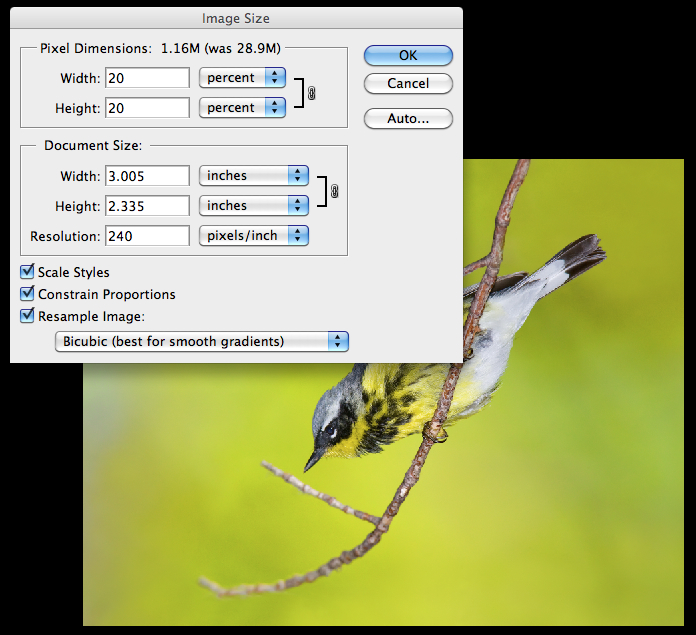

Fig. 12.7.2:

Sizing an image can be done based on absolute pixel dimensions

or as a percentage of the original image size. The Image Size

dialog box in

Photoshop indicates the target file size for a given target

resolution. You can

also specify a pixel dimension for one axis, and Photoshop will

automatically

compute the other axis dimension, subject to a fixed aspect

ratio. Several sampling

algorithms are available, but Bicubic (basic) works well without

introducing

too many artifacts; pre- and post-sharpening are recommended, to retain

maximal control over the final image (see the text).

One particular

setting in the Image Size window

to be careful about is the resampling algorithm (shown at the bottom of

the window in the figure above). In the preceding example, this

is shown as Bicubic; other

alternatives include Nearest Neighbor,

Bilinear, Bucubic Smoother, and Bicubic Sharper. The last of

these—Bicubic Sharper—is very

likely to tempt you at some point, once you notice the loss of detail

subsequent to resizing under the default algorithm (Bicubic). In my experience,

the Bicubic Sharper tends to

introduce artifacts and in general to just be too unwieldy. My

own approach to dealing with the loss of sharpness that typically

occurs under the default resizing algorithm is to apply a pre-sharpening before resizing and post-sharpening after

resizing. For the pre-sharpening, I use the Unsharp Mask with a radius of 0.3;

for the post-sharpening I use a radius of 0.15 or 0.2. In order

to find the ideal settings for the Amount

slider in the Unsharp Mask, I

typically go through several complete iterations of trying out

different settings for the Amount

of both the pre-sharpening and post-sharpening. This process may

sound laborious, and the first few times you do it it may be laborious,

but once you’ve got the hang of it it’s typically not very

time-consuming at all.

In terms of choosing the pixel dimensions, if you’re

posting the image to your own web site you’ll generally have complete

freedom to size the image as you like. To be practical, you’ll

generally want to size your web images so that they’ll easily fit

within the web browser window of the typical internet user. Doing

so helps to reduce the chance that your images will end up being

auto-resized by the user’s browser; these auto-resize

operations typically reduce image quality, and it’s thus best to avoid

them if possible. Assuming your user has his or her internet

browser maximized and is using a typical monitor of size 1440×900 or larger, the free space in

the viewing pane of the browser will typically be about 1024×768 (remember that the browser has

a menu bar, scroll bars, and typically a control panel with navigation

controls, and these all take up real estate on the screen). Thus,

you should try to keep your images smaller than 1024×768 to reduce the incidence of

auto-resize operations by the user’s browser.

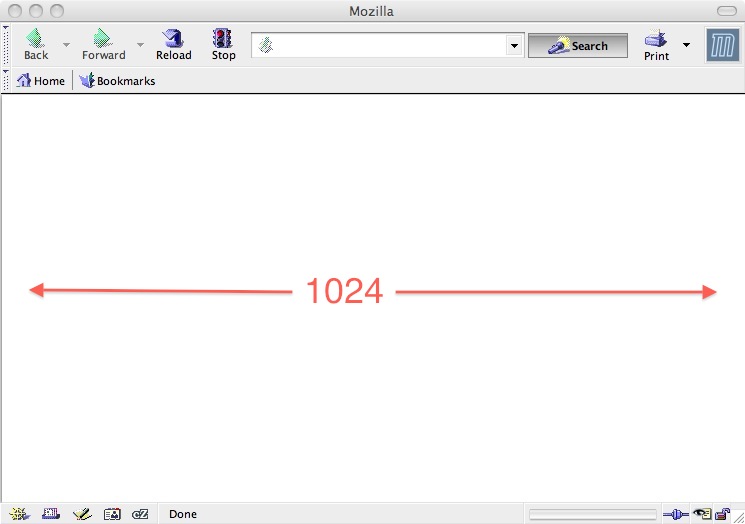

Fig. 12.7.3: Users viewing your images over the internet will see your

web page within the context of their browser window. Most

computer

screens these days are 1440x900 pixels or larger, but with the browser

taking up screen real estate for its various tool panels and the like,

you’re

best off budgeting for 1024x768 as the maximal size for your web images.

As of mid-2010, many laptops are selling with screen

sizes of 1440×900, while most stand-alone

computer monitors are in excess of 1280×1024 pixels. Keeping your

images small enough to display at full size on these devices (after

accounting for loss of real estate due to visual elements of the web

browser) will help to improve the chances that users will see the image

without any resizing artifacts introduced by their browsers.

Another thing you can do, when hosting images on your own web site, is

to encapsulate each image in its own HTML file. Some browsers

will resize images when the page consists of nothing but the image

itself, while images embedded within a proper HTML file will sometimes

be spared any resizing.

In terms of file size, there are a few things you

can do if you find yourself exceeding the limit of some online

venue. First, you can obviously reduce the file size by further

cropping the image, since cropping eliminates pixels and therefore the

need to encode those pixels in the file. Thus, when the

destination site imposes both resolution and file size constraints,

it’s best to first attend to the resolution constraints, and then to

see if, after having reduced the resolution as needed, there is still a

need to reduce the file size. If so, you can do so via the JPEG Options dialog box in

Photoshop, which will appear when you try to export a PSD or RAW file

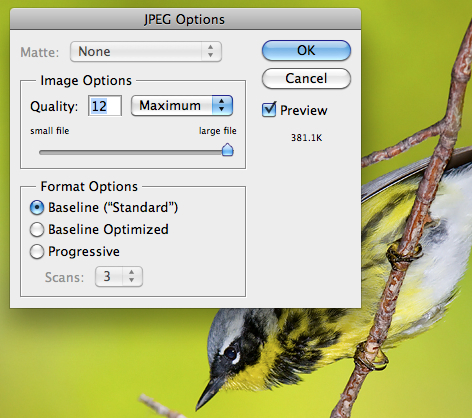

as a JPG image. This is depicted in the figure below.

Fig. 12.7.4: The JPG file format allows for variable quality

settings, which affect both image detail and file size. The only

way to be sure that your image will look acceptable at a given

JPG quality setting is to try that setting and view the resulting

file in a WYSIWYG viewer such as Photoshop.

For web images, many people use a default Quality setting of between 8 and

10, which in most cases should produce images with very reasonable file

sizes. Increasing the Quality

setting to 12 often results in a very substantial increase in file

size, and in many cases the difference in image quality between

settings of 10, 11, or 12 won’t be apparent to casual viewers.

Unfortunately, the only way to be sure is to try saving the image at

different Quality settings

and comparing them on-screen after re-opening the exported JPG

files.

The costs associated with posting larger image files

on the internet are gradually decreasing, but are still worth

considering at present. Keep in mind that not all of your users

may have high-speed internet access, so if you’re in the habit of

posting Quality 12 images approaching 1 Mb in size, you may find that

some users avoid your web site due to the slow download times of your

images. Depending on your hosting plan and the level of monthly

traffic to your site, you may also want to consider the impact of

posting large files on your monthly bandwidth quotas; for quality

hosting plans this won’t normally be an issue unless you’ve got

hundreds of thousands of viewers coming to your site every week.

For non-web deployment of images, sizing

considerations tend to be simpler, since you’ll generally want to use

the highest-resolution version of a file that you’ve got; this is

particularly true for print publication, where the ever-increasing

capacity of print devices tends mostly to place lower bounds rather than upper

bounds on practical image resolutions.

Now let’s consider what should, in most cases, be

the very final task prior to web publication of your newest bird photo:

proudly signing your name to your new masterpiece. In Photoshop

you need only invoke the Text tool,

click on the image where you’d like the signature to appear, and then

type your name. It’s a good idea to also include a copyright

notice, such as ©2010 before your name, if you’re concerned about

unauthorized use of your images.

Fig. 12.7.5:

Don’t be afraid to assert your rights by signing your art, but

try to do so in a manner that minimizes any impact on the image

aesthetics.

Position your signature in the left or right bottom corner of the

image, and

choose a font color that almost blends in with the background. A

good font

for signing your name in Photoshop is Dakota/Handwriting, though there

are

others that you might instead prefer.

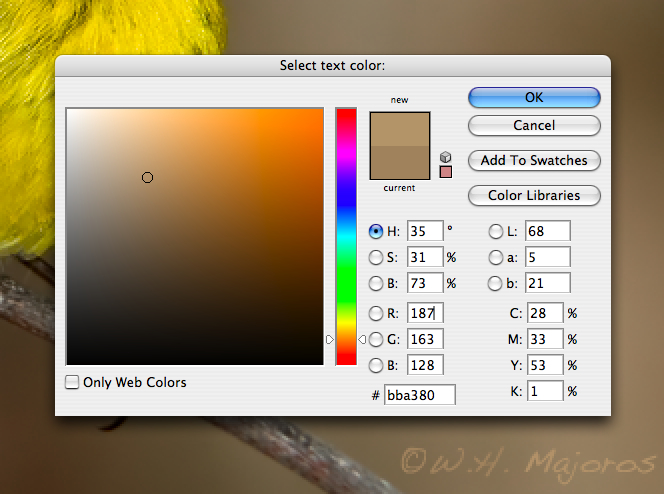

With the text tool still activated, you can click on

the color indicator near the top of the screen in Photoshop to bring up

the text color window (see the figure above). I highly recommend

choosing a text color that blends well with the part of the image

behind your name, so that your signature is clearly decipherable upon

careful inspection, but does not stand out in the image as a

whole. Viewers who want to know who the artist is will surely

inspect the lower left and lower right corners of the image (where your

signature should appear), while others who are uninterested in knowing

who deserves credit can still enjoy the image without being distracted

by a gaudy copyright sign—or, worse yet, a highly visible watermark

image superimposed in large strokes over the central part of the

image. When it comes to signing my own works, I take inspiration

from classical painters who signed their names discretely in some

out-of-the-way part of the painting near the bottom of the

canvas. This serves the twin goals of asserting the artist’s

rights while preserving the aesthetic impact and visual beauty of the

overall work.

|

|

|