|

Chapter

13

Advanced

Techniques

In this final chapter

of Part III we’ll consider some Photoshop techniques that might be

considered by novice users to be relatively advanced, though Photoshop “power

users” will no doubt find them trivial

and mundane. For

the online edition of this book, this section on advanced

post-processing techniques will likely grow considerably over time, so

please check back regularly for updates.

13.1

Replacing

the Background

The first technique we’ll consider

is that of replacing, wholesale, the entire

background region of the image. In section 12.6

we considered

methods for de-emphasizing the background, particularly through the use

of massive blurring to achieve an effect similar to the smooth bokeh

from a shallow depth of field. Two limitations of that method are

that the resulting backgrounds will still have roughly the same color

as before (though it can be modified via hue and saturation

adjustments), and that the resulting backgrounds can end up so smooth

and textureless that they look boring and artificial. While it’s

generally desirable to keep the background from being too detailed and

distracting, moderate amounts of detail in the background can be

beneficial, because it gives the viewer’s eye something to contemplate

after s/he has had a chance to take in the foreground. Indeed, as

we mentioned in section 8.1, the visual

dynamics that result from

foreground and background competition for the viewer’s attention can

(in some cases) improve the overall aesthetics of an image. When

the original background of an image doesn’t satisfy these

considerations, replacing the background with that from another photo

can sometimes help to improve the image.

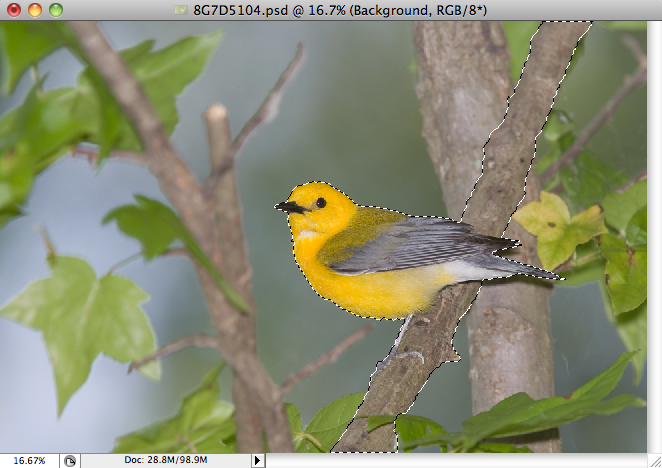

The figure below illustrates some of these subtle

issues. The image on the left is the original; the image on the

right shows the result of replacing the background with a less “busy”

one. The image on the right clearly focuses the viewer’s

attention on the bird more than the image on the left, but it also

drastically alters the overall color composition of the scene. In

cases like this, it may be better to instead explore your options for

improving the existing background through the judicious use of blurring

and selective editing (e.g., removing the tree branch in the background

via the Clone tool—see section 11.5).

Fig. 13.1.1:

Replacing the background of an image is a very powerful

technique, but it’s not always the best course of action. In this

case, the

original image (left) had lots of nice background color; the distracting

branches could have been erased via the Clone tool. After

replacing

the background (right), the image is less cluttered, but also somewhat

less interesting. Finding the right balance is What It’s All

About.

Actually replacing the background

is, in many cases, not nearly as difficult as you might imagine—as long

as you’ve got a background image that you can use. You’ll

generally want to use an entire image for the new background, rather

than trying to copy the background from part of another bird

photo. I make a point of taking a few severely out-of-focus

photos (of the scenery, not of a bird) in each shooting environment I

find myself in, in case I need to replace any bird photos’ backgrounds

and want the color composition to remain consistent. I also try

to collect such background images into a central place in my archives,

so I can easily find a background when needed.

The following series of figures illustrates the

actual replacement technique in simple

steps. The first step is to select the foreground—including

both the bird and any other elements that you want to retain in the

image—and to save that selection into a named channel (see section

10.6). The

figure below shows the original image and foreground selection.

Note that for this application (replacing the background) it’s

typically the case that you’ll want to be fairly exacting in your

selection; for this example I zoomed in and refined the edges of the

selection by nudging them as needed with the Quick Selection

tool. As we’ll see in a bit, errors in the selection can

be

mended later by instead modifying the layer mask that we’ll be creating

for the background layer; nevertheless, I personally prefer to refine

the selection boundaries during the actual selection phase, since I

find the Quick Selection tool

to be very efficient for this task, even

when working at the level of fine details on the zoomed-in image.

Just how finely those details need to be followed depends, of course,

on what you intend to do with the image: for posting small resolution

images on the internet, the finest details can often be ignored, while

for printing on large media you’ll likely want to be more exacting.

Fig. 13.1.2:

Preparing an image for background swapping. First,

select all of the foreground elements that you wish to retain in the

final

image (depicted here). Then invert the selection so that the

background

is selected instead of the foreground (not shown here). Save the

background

selection. When you’re ready to create the new background layer,

this selection

will be used to create a layer mask for the background layer, which

will permit

the foreground pixels to show through from the underlying layer.

Once you’ve got the foreground

selected, you can invert it (via Select

> Inverse) and then save the resulting background selection

to a named channel. You can now load your background image into

Photoshop, select the

entire background image, copy it via Cmd-C

/ Ctrl-C, and then paste it

as a new layer in the first file (via Cmd-V

/ Ctrl-V). In the Layers

panel

you’ll see two layers: the original foreground layer at the bottom

(which will, unfortunately, be automatically labeled “Background” by

Photoshop), and the new background layer, which will be above it.

Next, click on the new background layer in the Layers panel, and bring up the

background selection via Select >

Load Selection (or, alternatively, bring up the foreground

selection and invert it). The

inverted outline of the foreground should now be superimposed on the

background

image, via the original foreground selection. With the

selection still active, click on the Add

Layer Mask button at the

bottom of the Layers

panel. A layer mask will be created, with

the mask initialized to the (inverted) shape of the foreground.

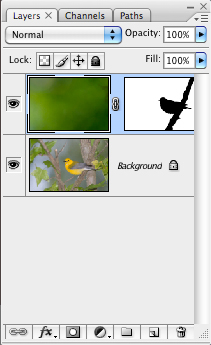

The figure

below illustrates what you should see in your Layers panel after doing

this.

Fig. 13.1.3:

The Layers panel after pasting in

the new background layer. Take note of the

layer mask, which as you can see takes the

shape of a bird on a branch. The layer mask

is what allows the foreground to show through,

by defining the transparent region of the background

layer. You can refine the layer mask as needed to

achieve smoother blending effects.

Fig. 13.1.4: A

preliminary version of the merged image. The foreground

shows through, just as planned. However, some of the foreground

edges

appear unnatural, due to the shallow depth of field (particularly at the

far end of the branch, which is out of focus). These types of

artifacts

can be corrected by blurring parts of the layer mask.

Notice in the figure above that

the far end of the branch looks odd: its edges meet too abruptly with

the background. The problem is that the far end of the branch is

out of focus (due to the shallow depth of field) and therefore soft,

but the edges appear unnaturally hard due to the layer mask.

Normally, the edges of out-of-focus

objects appear very soft. We could have prevented this by feathering

(section 10.6) just that part of the selection

prior to creating the

layer mask, but

we can achieve the same effect now by using a soft-edged brush to paint

along the edge of the layer mask. The layer mask is black and

white (actually, grayscale),

so when softening edges in the layer mask you just need to

choose a black or white color for the brush (or a shade of gray).

Click on the layer

mask itself (to indicate to Photoshop that you want to modify the

pixels of the mask rather than the actual image pixels of the layer)

and then simply paint with the soft-edged brush in the main window in

Photoshop. As you paint you’ll see the pattern in the layer mask

changing, and you’ll also see the effects of changes to the layer’s

transparency, as more or fewer of the pixels from the lower layers

show through (in the main Photoshop window). The figure below

shows the result of softening the edges of the distant part of the

branch in this way. The near part of the branch was also repaired

using the Clone tool.

Fig. 13.1.5:

The corrected image, after blurring parts of the layer mask

and repairing the nearer portion of the branch using the Clone tool.

Note that

softening the edges of a layer mask can also be done by selecting parts

of the layer mask and applying Gaussian

Blur. Indeed, just about

any adjustment that you can make to a layer’s pixels can also be made

to a layer’s mask, since the mask is itself nothing more than a

grayscale image. The black pixels in the layer mask cause

the corresponding pixels in the layer to be transparent, while the

white pixels in the mask cause those pixels in the layer to be

opaque; shades of gray impose corresponding degrees of opacity and

hence cause blending. Applying effects like Gaussian Blur to the mask alters

the mask’s pixels, which in turn alters the transparency pattern of the

layer. In section 13.2 we’ll use this

fact to create artificial

clouds in the sky by rendering cloud patterns into the layer mask, so

that lighter pixels from a lower level show through those

semi-transparent areas. A similar trick can be used to add

texture to a background by duplicating the background, modifying the

brightness of the lower layer, and then painting into the upper layer’s mask with

an appropriately textured brush.

The figure below shows a more challenging example,

where more subtle blending of the foreground and background layers was

required in the wings, due to the motion blur. This was achieved

in this case by painstakingly brushing over appropriate parts of the

wings in the background layer mask with a soft, low-opacity brush to

allow the background to show through a bit in those regions; it’s

likely, however, that a simpler approach could have been found, such as

via the use of blurring filters (applied to the layer mask) or

feathering (applied earlier, during selection). Remember that

there are usually multiple ways to achieve the same thing in Photoshop,

and some of those ways often take far less effort than others.

Fig. 13.1.6: A

more difficult exercise in image compositing.

The motion blur of the wings introduces considerable difficulty, since

the original background differed in color from the new background.

This was rectified here via very careful use of a soft-edge, low-opacity

brush applied to the layer mask of the background layer, to achieve

a more realistic blending.

If you look closely enough at the

above figure, you’ll surely find some processing artifacts (such as the

thin, dark line along the belly). After performing major image

surgury like that illustrated here, it’s a good idea to go over the

image with a fine-toothed comb to search for any artifacts that need to

be cleaned up after the fact. I recommend zooming in one or two

factors of magnification and then panning over the whole image to look

for defects. Some defects you’ll be able to repair fairly simply,

by modifying a few pixels in a layer mask. Others will require

the use of the Clone tool.

If you haven’t yet mastered the Clone

tool, then it’s a good time to start getting more experience

with it; many advanced post-processing techniques depend crucially on

either this tool or on the use of related methods that result in

copying pixels from one place in the image to another (or from another

image altogether, as in the case of replacing a scene’s natural

background).

In this section we’ve relied heavily on the use of

layers and layer masks. It’s worthwhile to just briefly mention

two related layer-oriented tricks that you can use in your

post-processing, either to simplify things or to reduce memory

requirements (or both). Duplicating a layer obviously incurs a

memory cost, since all of the pixels in the original layer now need to

be represented twice. This will result in larger file sizes and

in greater demands on run-time memory, which may or may not be an issue

for you, depending on how souped-up your computer is. The first

trick is the use of smart objects

in Photoshop. When clicking the Open

Image button in Adobe Camera Raw (ACR), if you hold down the Shift key while clicking the

button, the Open Image button

should change to say Open Object.

The image will then be opened in Photoshop as a smart object rather than as a

standard image file. The difference is that any filters or

effects that you apply to the image will be stacked into a set of smart filters to be dynamically

evaluated during rendering of the image, rather than being applied

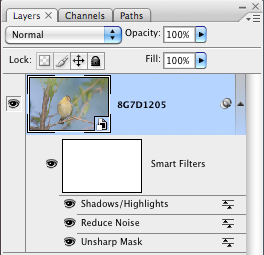

statically to the layer’s pixels right then and there. The figure

below shows the Layers panel

after three image effects (Shadows/Highlights,

Reduce Noise, and Unsharp Mask) were been applied to

a smart object.

Fig. 13.1.7:

Smart objects and smart filters.

When a RAW file is opened as a smart object

(by pressing the Shift key while clicking Open

in ACR), any filter that is applied to the image

then becomes a smart filter. By clicking on any

of the smart filters that have been applied (in the

layers panel), you can then adjust any of their

parameters. You can also drag them up and

down in the stack to change their ordering.

The advantage

of smart filters is that they automatically update the image whenever

anything in the filter chain changes. For example, if you insert

a new filter partway through the filter chain (say, between Unsharp Mask and Reduce Noise in the example above),

all filters above this in the chain will be dynamically re-evaluated

and the sum effect on the rendered image will appear on screen in “near real time” (though on many computers this

can be a slow process, so “near real time” is rather relative). The

importance of ordering in the filter chain should be obvious if you

think about a simple example: sharpening versus noise reduction.

Since sharpening emphasizes noise, sharpening before noise reduction can make the

noise reduction less effective. On the other hand, noise

reduction obliterates details, so sharpening after noise reduction may result in

less subject detail. Deciding on the ideal ordering may require

you to consider both orderings as well as different parameter settings

for both filters. The point is simply that ordering does matter,

and with smart filters you can modify that ordering by simply dragging

the filters up or down in the stack using your mouse.

Smart objects and smart filters fall under the

rubric of what digital artists call nondestructive

editing—that is, editing operations that don’t actually modify

the original, underlying representation, so that they can be undone at

any point in the future. By comparison, although the history facility in Photoshop

(section 10.5) provides a sort of “undo” capability, undoing something far

back in time requires that everything done between then and now also be

undone. Editing in this paradigm is very linear (in time).

The goal of nondestructive editing is to allow adjustments performed

arbitrarily far back in time to be re-parameterized as needed.

For example, in the above figure we sharpened the image prior to

reducing noise and then adjusting the shadows and highlights. If

we then decide that the image looks a bit over-sharpened, we can go

back and adjust the sharpening parameters (e.g., the amount and radius)

without having to undo the noise reduction and shadow/highlight

adjustment. The changes to the sharpening parameters will

automatically propagate through the smart-filter chain, and the result

will be apparent on-screen in near real-time. I personally don’t

use smart objects much, because on my computer (a newest generation

Apple laptop) there is still a bit more latency in the updates of the

filter chain than I’d like. But I still think it’s a great idea,

and if I wasn’t so lazy I’d spend more time trying to get used to using

it.

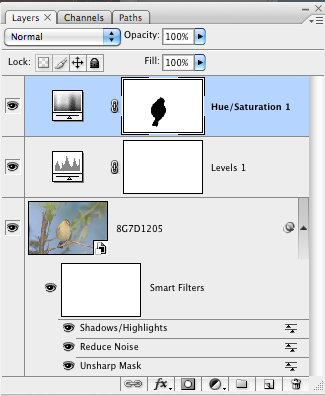

Another great idea that I personally don’t use much

(but probably should) is the adjustment

layer in Photoshop. Adjustment layers are basically just

like smart filters, except that they can be applied to any image, not

just to smart objects. In Photoshop version CS3, smart filters

are primarily limited to true filters (under the Filter menu), largely precluding

other operations such as those under Image

> Adjustments. Adjustment layers remedy this

shortcoming by permitting non-filter image adjustments to be applied in

a manner just like smart filters. The figure below shows an

example. The smart object is the lowest layer; above this we’ve

applied two adjustment layers: Levels,

and then Hue/Saturation.

The parameters of either of these adjustments can be changed at any

time by simply double-clicking the adjustment layer, which will bring

up the appropriate adjustment dialog with all the parameter

sliders. You can then change any of the sliders, press Enter/Return and see the result as

the image is automatically updated to reflect the parameter

changes. Note also that adjustment layers can have their own

layer masks, so they can be applied to specific parts of an image, just

as with traditional selection-based processing (i.e., the D-PIE technique described earlier: Differential Processing of Image Elements).

Fig. 13.1.8:

Adjustment layers. Here, we’ve applied

three smart filters to a smart object, and then applied

two adjustment layers (Levels and Hue/Saturation),

which are shown as layers above the smart object.

By clicking on either adjustment layer we can update

the adjustment parameters at any time. Adjustment

layers can also have layer masks, so that adjustments

can be applied just to specific parts of an image if desired.

Smart filters

and adjustment layers can be great time savers, because they allow you

to go back and correct parameter settings long after you originally

applied the effect. Without these special features, you’d have to

undo everything since the original effect was applied, redo the effect

with the new parameters, and then replicate all of your processing

since them. One thing that I don’t like about these dynamic

filter chains is that the preview that I see on-screen sometimes seems

to differ in subtle ways from what I see when I export the image as a

JPG and then view the resulting JPG file statically. Whether this

is still an issue with the newest versions of Photoshop is unknown to

me at this point. Also, it’s entirely conceivable that there may

be instances in which you wouldn’t want changes to layers lower in the

stack to be reflected in higher layers; this would presumably require a

change back to the opaque layer method—i.e., avoiding the use of an

adjustment layer or smart filter.

|

|

|